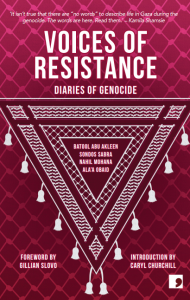

Palestinian poet Ahmad Almallah’s second collection, Border Wisdom, is a searing love song of longing, memory, and language. It is a heart-wrenching evocation of the poet’s mother, Nawal, and of the poet’s own identity, familial lineage, and their occupied homeland. Woven with epigraphs from Ahmad Shawqi and Emily Dickinson, the collection propels itself smoothly between English and Arabic with erasure poetry, Arabic khatt, shape-poems, and English prose that chart the poet’s topographies of Philadelphia, Beirut, Vermont, and Bethlehem, along with the reimagined terrain of his mother’s Amman and al-Khalil.

Border Wisdom pulsates with the poet’s estrangements: from his home, from his father, from the contours of his own memory. And echoing through as though an aftershock is a disclosure from the book’s last few pages: “Dear reader, I’ve been pretending all along to have a second language. Actually/in reality/basically/essentially/ I don’t know anything in Arabic.”

In this conversation, I spoke with Dr. Almallah about Border Wisdom, mistranslations, and his labyrinthine poetics of negotiation between Arabic and English.

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (AMMD): Your second poetry collection, Border Wisdom, was published by Winter Editions in 2023. How did the poems in this collection come together over time? And what has the experience of sharing this work with the world been like for you?

Ahmad Almallah (AA): The poems began to come together before and after my mother’s disappearance from this world. The world of borders did not allow me to be by her side in her final hours. It was in 2021; I was trying to be there for her but the Israeli Occupying Forces (IOF) launched a large operation to quell protests over kicking people out of their homes in Sheikh Jarrah, and Gaza ended up being hit the hardest as Israel was flexing its military power on innocent Palestinians as has been for seventy-seven years now.

At that point, I chose to leave the West Bank to be with my family in the US. A week after that I got news that my mother was no longer of the living. I was advised not to go back. I found myself flipping through the poems of Emily Dickinson and I happened on the line “there is a finished feeling at the grave.” It was then that I decided to go back to Palestine. The first thing that came to my mind when I walked into the room where my mother spent the final days of her life was that she was not dead. She had just disappeared. And the same thought stayed with me when I visited her grave. I wasn’t there to witness her body put in the ground. This is when I began to hold onto the idea of disappearance as an alternative to death. READ MORE…