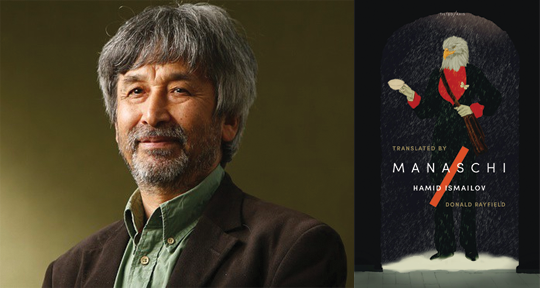

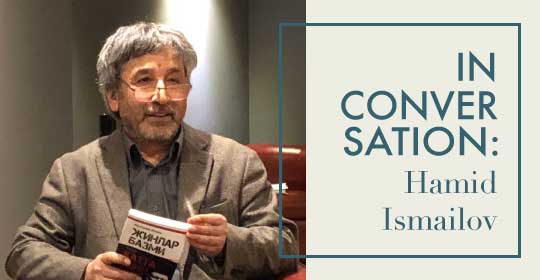

In part one of this interview, translator Shelley Fairweather-Vega spoke to Willem Marx regarding the complex, genre-traversing works of Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov, whose dramatic work, “Trinity,” was featured in our Spring 2024 issue. Today, we continue the conversation with an extended discussion of Central Asian literature—including the collection Amanat, a pioneering compilation of contemporary Kazakh women’s writing, edited by Fairweather-Vega and author Zaure Batayeva; the importance of raising women’s voices; shaking off old Soviet literary hierarchies; the complexities of working from pivot languages; and the links between colonialism and ecological disaster in Central Asia.

Sarah Gear (SG): You translate from Russian and Uzbek, and also work from Kazakh. How did you come to learn these languages, and what have the main challenges been?

Shelley Fairweather-Vega (SFV): That’s right, and in the past year, I’ve made it through a Kyrgyz book, as well as an Uzbek text that includes Turkmen and Tajik—so my collection of major Central Asian languages is now pretty much complete. I know Russian very well, having studied it and worked in it for the longest by far, and having lived and worked in Russia for two years. I often tell people that I began learning Uzbek to pay my way through graduate school, which is the truth: fellowships for Uzbek paid for an intensive summer course and the last year of my master’s degree. Of course, I didn’t do it just for the money; I was studying the politics and recent history of the region, and had the sense that only knowing Russian would give me an incomplete picture of Central Asian society, not to mention its literature. When I began translating more work from Kazakhstan, I signed up for another intensive summer course, this time for Kazakh. The grammar and a lot of the vocabulary was very familiar to me from Uzbek, and now I’ve got a big Turkic section of my brain where Uzbek, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz words all jumble together. This means I can’t speak or write very well in any of those languages, but reading and translating them works out quite well, if I’m careful—and I try to be careful.

SG: You worked with Kazakh author and translator Zaure Batayeva on Amanat, a collection of Kazakh women’s fiction published in 2022. Why did you decide to focus on contemporary women’s writing?