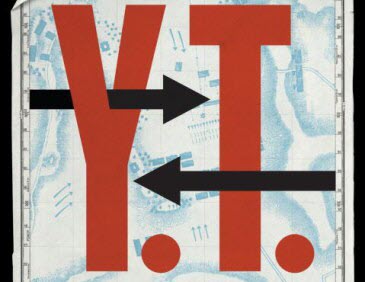

In a collection that coheres pivotal ideas about womanhood and history with impeccable craft, Ukrainian writer Oksana Zabuzhko has once again impressed her brilliance upon the English-speaking world with the newly released Your Ad Could Go Here. At Asymptote, we are incredibly proud to present this volume of stunning short stories as our Book Club selection for April. Known equally for her adeptness in criticism and philosophy as her accomplishments in poetry and fiction, Zabuzhko’s refined perspective on Ukrainian identity and feminism, enlivening her characters and narratives, is a gift for readers everywhere.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

Your Ad Could Go Here by Oksana Zabuzhko, translated from the Ukrainian, edited by Nina Murray, Amazon Crossing, 2020

As I read Oksana Zabuzhko’s newest collection of short stories, Your Ad Could Go Here, I recalled the scene in Paradise Lost when Eve, new to the world, is startled to encounter her own reflection in a pool of water:

As I bent down to look, just opposite

A shape within the watery gleam appeared,

Bending to look on me: I started back,

It started back; but pleased I soon returned,

Pleased it returned as soon with answering looks

Of sympathy and love: There I had fixed

Mine eyes till now, and pined with vain desire,

Had not a voice thus warned me; ‘What thou seest,

‘What there thou seest, fair Creature, is thyself

Like Milton’s Eve, Zabuzhko’s protagonists—invariably women—turn their attention inward, without losing sight of their physical selves. They find strength, power, faults—and a wellspring of self-love, despite being riven by the natural contradictions of a full life. READ MORE…