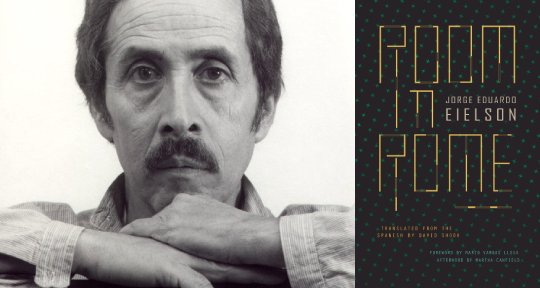

Room in Rome, by Jorge Eduardo Eielson, translated from the Spanish by David Shook, Cardboard House Press, 2019

Knots

That are not knots

And knots that are only

Knots

- Peruvian poet Jorge Eduardo Eielson once said of César Vallejo: “There is no superfluousness in Vallejo’s poetry, just as there isn’t any in Christian mysticism, although for opposite reasons”. This reason, according to Eielson, is that Vallejo’s poetry, as opposed to Christian mysticism that supposes a martyrdom of the body, is “a descent of the body—fleshly and social—into hell, that supposes another martyrdom, that of the soul.”

- Eielson writes the fleshly and social descent of the body into the Eternal City. Just looking at the title of the opening poem confirms Eielson’s commitment to the body: “Blasphemous Elegy for Those Who Live in the Neighborhood of San Pedro and Have Nothing to Eat.” Room in Rome was written in 1952, shortly after he had left Peru for Italy, where he would settle until his death in 2006. Vallejo, his hero, would also leave Peru for France. Despite this, Eielson’s book was widely available until 1977. During this period, he produced the novel El cuerpo de Gulia-no (The Body of Gulia-no). Again, its title suggests a rigorous investigation of the body and its descent into the worldly. Eielson would write, in 1955, Noche oscura del cuerpo (The Dark Night of the Body)—a shout-out to the Christian mystic St. John of the Cross.)

- “i have turned / my patience / into water / my solitude / into bread”

“here i am headless and shoeless”

“our father who art in the water”

“love will be reborn/ between my parched lips”