Experience the world anew through non-human eyes in “Vivarium,” our Spring 2023 issue! From macaques to marmots, muntjacs to mosshoppers and microscopic prokaryotes, a superabundance of literary life overflows from 30 different countries. In this thriving biosphere, you’ll find work from Estonia and Oman flowering in the same soil as Alaa Abu Asad’s Wild Plants and our first entry from Bolivia via Pulitzer Prizewinner Forrest Gander. The same Pangaean ecosystem sustains our animal-themed special feature headlined by Yolanda González, recipient of the 2001 Premio Café Gijón Prize, and 2018 Booker International longlistee Wu Ming-Yi. Alongside these, there are the always thought-provoking words of Italian poet Franca Mancinelli, which bloom in both the Interview and Poetry section—the latter also shelters Fernando Pessoa, whose brilliant co-translators Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari have rendered him in one of his most mordant heteronyms, Álvaro de Campos.

Language: Spanish

Our Spring 2023 Edition Is Here!

Featuring Fernando Pessoa, Franca Mancinelli, Wu Ming-Yi, and Yolanda González in our animal-themed special feature

Traitor to Tradition, Resister to Remorse: A Conversation with Kiran Bhat

I want to shift the story before the labels set in; I want to blur the border before it has had time to be constructed . . .

Khiran Bhat is true to what he says he is: a “citizen of the world.” Among other things, he has authored poetry volumes in both Spanish and Mandarin, a short story collection in Portuguese, and a travel book in Kannada. He is also a speaker of Turkish, Indonesian, Hindi, Japanese, French, Arabic, and Russian, and has made homes from Madrid to Melbourne, from Cairo to Cuzco.

In this interview, I asked Bhat about writing across genres, self-translating from and into a myriad of languages, and being a writer who identifies as planetary, belonging to no nation—and thus, all nations at once.

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (AMMD): As a polyglot, a citizen of the world, and a writer “writing for the global,” are there authors (especially those writing in any of the twelve languages that you speak) whom you think were not translated well, and therefore deserve to be re-translated?

Kiran Bhat (KB): What an interesting question! I’m rarely asked about translation, and since I dabble in translation, I’m glad to see someone challenge me on a topic that speaks to this side of myself.

It’s a hard one to answer. I would pose that almost all books are badly translated because no one can truly capture what an author says in one language. Every work of translation, no matter how ‘faithful’ it aspires to be, is essentially an interpretation, and that interpretation is really a piece of fiction from the translator. Some people really want ‘authenticity,’ but when I read a translation, I just want something that compels me to keep reading (probably because I’m so aware of the ruse of it all).

For example, a lot of people prefer the Pevear and Volokhonsky translation of War and Peace, but I fell in love with the Constance Garnett translation. This might have been because it’s easy to find on the Internet and I was reading it on my computer while waiting on a ferry crossing Guyana and Suriname in 2012, but Garnett’s effortless storytelling style really made me fall in love with Pierre and Natasha. I can understand why technically Pevear and Volokhonsky are truer to Tolstoy’s sentences and paragraph structures, but I feel riveted when I read the Garnett version. I want to turn the pages and find out what’s going on, and I think that’s important as a reader: to get lost and immersed in a fictional world.

Translation Tuesday: “Zinc” by Róger Lindo

The rodent will be captivated, as I will, by the hailstones lashing against the roof.

Salvadoran poet Róger Lindo tr. Matthew Byrne sets a tempestuous scene: a night storm both ethereal and mundane that compels all, from the dormouse to the soldier, to collective awe. This Translation Tuesday, we invite you to bear witness to ‘the nocturnal splendor’.

“Zinc”

I have only hubris and kindness.

–G. Ungaretti

Beastly storm.

A dormouse peers out halfway.

The rodent will be captivated, as I will,

by the hailstones

lashing against the roof.

The city mnemonist is here,

a soldier yearning,

drawing near, intrigued by

the nocturnal splendor.

I’ve been a solitary worker bee

in the afternoon,

but I’ve also sung

plowing the soil.

When the rain eases off,

we’re alone with the crickets.

Translated from the Spanish by Matthew Byrne.

Weekly Dispatches From the Front Lines of World Literature

The latest in literary news from Palestine and Mexico!

This week, our Editors-at-Large bring us updates on prestigious awards and literary festivals from Palestine and Mexico! From the 2023 winners of the Mahmoud Darwish Award for Creativity to multisensorial poetry from the UANLeer book fair, read on to learn more!

Carol Khoury, Editor-at-Large for Palestine and the Palestinians, reporting from Palestine

The 2023 edition of the Mahmoud Darwish Award for Creativity has been announced, with three winners selected from different categories. In the Palestinian Creative category, Palestinian poet and academic Dr. Salma al-Khadra al-Jayyusi won for her significant contributions to contemporary Arabic poetry, including leading a translation project that brought several notable works to English readers.

Lebanese composer, singer, and musician Marcel Khalife won the Arab Creative category for the remarkable additions he has brought to Arab musical heritage. Khalife is known for his devotion to Palestinian poetry, particularly that of Mahmoud Darwish, and has left an indelible mark on the Arab audience’s consciousness.

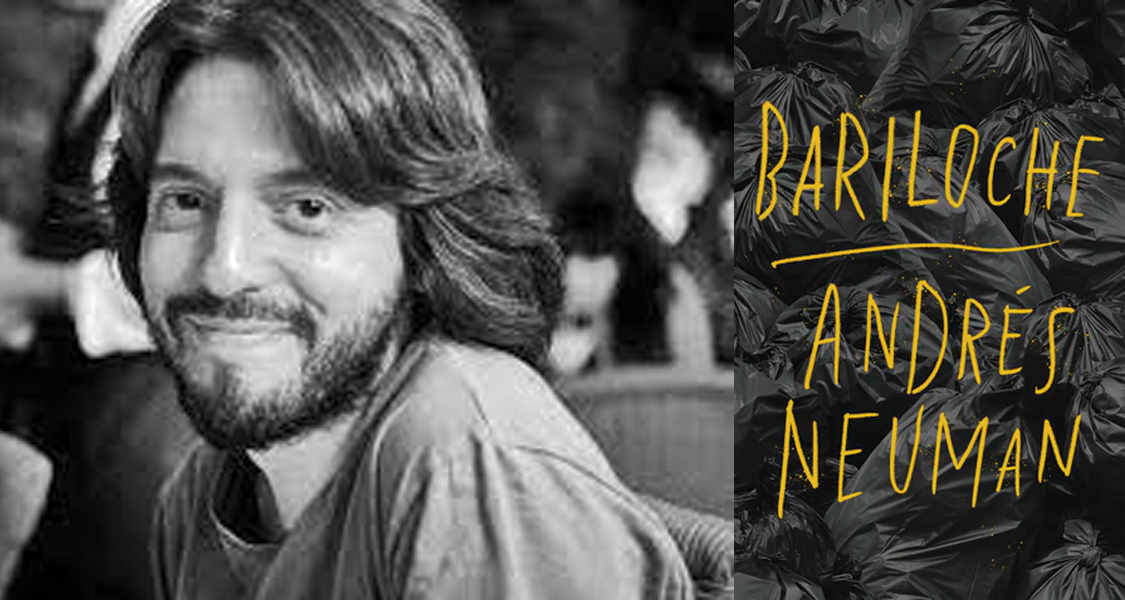

What Exists Where You Do Not See: On Andrés Neuman’s Bariloche

Bariloche is bleakly luminous and fascinatingly fractured.

Bariloche by Andrés Neuman, translated from the Spanish by Robin Myers, Open Letter, 2023

Andrés Neuman’s first novel, originally published in 1999, is his fourth to be translated into English—following Traveller of the Century, Talking to Ourselves, and Fracture. Any thoughts of difficulty or inadequacy suggested by this twenty-odd-year delay can be quickly dismissed: it is worth the wait. Finalist in the Herralde Prize, and described by Bolaño as containing something “that can be found only in great literature, the kind written by real poets,” this story of a trash collector living in Buenos Aires who obsessively compiles puzzles depicting the region of his childhood—the Bariloche of the title—is densely powerful.

The narrative follows Demetrio as he goes about his job collecting trash with his co-worker, El Negro. They work while the city (or most of it) sleeps, stopping only to breakfast on cafe con leche and medialunas, occasionally inviting a homeless person to join them. Their dialogue is simple, and El Negro talks far more than Demetrio, who is absorbed in thought—or in nothingness, El Negro can’t tell. After work, in the early afternoon, Demetrio returns home, where he collapses into bed, finding a kind of brief relief there:

He went to the bathroom, pissed with relish, took off his shoes, stroked his pillow, breathed between the sheets, the sheets were dissolving into something else becoming water, becoming waves.

Celebrate International Women’s Day with Women’s Writing!

Join us as we highlight the vital contributions of women to literature and translation.

March 8th is International Women’s Day, and we wanted to take the opportunity to lift up the work of women in world literature. Below, find a selection of pieces published on the blog in the past year, across essays, reviews, translations, and interviews, curated to represent the breadth and brilliance of women working in writing.

Interviews

A Conversation on Kurdish Translation with Farangis Ghaderi

by Holly Mason Badra

But when you look deeper, when you look at archives, and look at early Kurdish periodicals, you find women. You discover these forgotten voices. An interesting example of that is Zeyneb Xan, who published under the pseudonym of Kiche Kurd (“Kurdish girl”). In 2018, when a publisher was reprinting Galawej (the first Kurdish literary journal published in 1939–1949), they decided to have sections on contributing writers. They came across this name, and one of the researchers working on the project uncovered that the identity of the writer was Zeyneb Xan (1900–1963), the eldest sister of Dildar—a very well-known figure of Kurdish literature who wrote the Kurdish anthem. Although her family was a literary family and at the center of literary attention, her manuscript remained unpublished until 2018. Her truly fascinating poetry collection covers a wide range of themes from patriotism to women’s education and liberation.

Wild Women: An Interview with Aoko Matsuda and Polly Barton

by Sophia Stewart

For me, films and television programs, as well as books and comics, have always been the places where I can meet outsider women, weirdo women, rebel women, sometimes scary women. When I was a child, I didn’t care if these women were human beings or ghosts or monsters, and I didn’t care if they were from Japan or other countries. I was just drawn to them, encouraged by their existence.

To Protect Oneself From Violence: An Interview with Mónica Ojeda

by Rose Bialer

Maybe if I was born in some other place, I would be writing about something else, but I do believe that Latin America is a very violent continent, especially for women, and in all of our traditions of women’s literature, there have always been women writing horror stories in Latin America. . . I do believe that it’s because you can’t write about anything else. That’s how you live life. You are afraid for your life. You are scared of the violence in your family, the violence between your friends, the violence in the street. You can’t think about anything else except how to protect yourself from violence.

Where the Poems Live: In Conversation with Katherine M. Hedeen and Olivia Lott

There’s a rawness, an honesty, and an urgent need of poetry that is both captivating and heartbreaking. Queerness is at the center of that . . .

Last fall, Katherine Hedeen and Olivia Lott published Almost Obscene (Cleveland State University Poetry Center), a wide-ranging selection of poems from Colombian poet Raúl Gómez Jattin (1945–1997), introducing English readers to the poet for the first time.

Gómez Jattin’s poetry defies the contemporary impulse to categorize a book of poems or its poet in any straightforward fashion. A Colombian poet of Syrian descent, born in Cartagena, Gómez Jattin wrote from the margins of his literary culture on topics ranging from mental illness to homosexuality to drug use to Greek mythology; the distance between the poet’s life and his subject(s) often seems imperceptible.

I recently had the chance to interview both translators over a series of emails, during which we discussed the collaborative process of translating this book together, as well as the “deceptively simple” queer poetics of Gómez Jattin, and exactly where in the body his poems ‘live.’

M.L. Martin (MLM): Thank you, Katherine and Olivia, for making time to discuss this powerful and important book, Almost Obscene, which is out now with Cleveland State University Poetry Center. I’m always curious about how translators find and connect with their translation projects. How did you first encounter Raúl Gómez Jattin’s work? And what aspects of his work—and his biography as a marginalized queer Colombian poet of Syrian descent—did you wish to share with English readers?

Katherine M. Hedeen (KMH): I first heard of Raúl when I traveled to Medellín, Colombia in 1997 to attend the International Poetry Festival. He had been a good friend of Cuban poet Víctor Rodríguez Núñez, whom I was traveling with, and he had just died. It was big news at the festival. Raúl was a controversial figure in Colombian poetry, as you can imagine, and the rebel rouser organizers of Medellín’s poetry festival had supported him. I got to know his work through Víctor; which I found both compelling and heartbreaking. He had been on my list of poets I wanted to see in English translation. Fast forward to 2012. Olivia was a student in my literary translation course at Kenyon College. Back then, I’d assign each student a poet to translate, normally one who hadn’t been translated yet. I assigned Raúl to her. She loved the work and eventually her manuscript became her honors thesis in Spanish at Kenyon. At this point, the project was all hers. I had only been involved as her thesis advisor.

Olivia Lott (OL): Just as Kate says, Raúl was the first poet I translated, as part of her literary translation course and then honors thesis. The project took me to Colombia, where I taught English through the Fulbright Program and spent weekends and holidays traveling around the country to meet poets. My year there gave me time to read a ton of Colombian poetry and to get a sense of the literary scene. I always kept Raul’s work in mind. I was struck by how he was often excluded from national anthologies, and how even in Cartagena (the city where he lived most of his life) his work was difficult to track down in local bookstores. Through this experience I began to translate other poets, but I never abandoned the Raúl project, in part due to the possibility of “righting” his legacy through giving his work a second life in English-language translation.

Translation Tuesday: “Return” by Cristalina Parra

my mother’s eyes in the morning and my father / ringing the doorbell, atop his bike, without shoes...

This Translation Tuesday, we bring you poetry from Chilean poeta Cristalina Parra’s debut collection Tambaleos. Translated from the Spanish by Julián David Bañuelos, “Return” is a tidal wave of nostalgia–overwhelming and sweet.

while swapping my papers, my mountains for the

desert gulf, i think about the reflections of clouds

cloaking the Santiago Mountain or the sun–

rise measuring the length of your face, slowly

cracks the day, there, the winds cross

the valley, the leaves sing and the clouds dance, I

hear the music you sent and the music we listened

to while running from the pigs, i think of all

the shellfish in this cold ocean and how the squids,

before death, try for the shore, i see,

my mother’s eyes in the morning and my father ringing

the doorbell, atop his bike, without shoes, his olive

skin, i think about the pup attempting their first

steps and the whiskey i threw back with my cousin

while playing Charlie Garcia’s keyboard and

chatting about the void we both understood, I think of the sunrise

for the first time in three years.

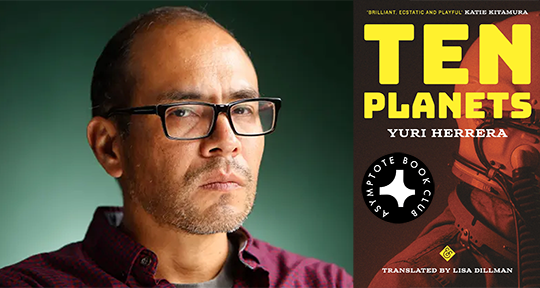

Announcing Our February Book Club Selection: Ten Planets by Yuri Herrera

Science fiction is Herrera’s springboard for a ludicrously inventive imagination.

Many are likely to be acquainted with celebrated Mexican writer Yuri Herrera by way of his novels, but in this latest collection of short stories, the author extends his brilliance to a vast array of disciplines and subjects. With elements of politics, philology, science, and storytelling, these tales not only display the talents of a master craftsman of language, but also an endlessly inventive imagination, a sharp humour, and a fascination with how this world—and other worlds—work. As our Book Club selection for the month of February, we are proud to bring to our readers this riveting constellation of ideas and dimensions.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Ten Planets by Yuri Herrera, translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman, Graywolf Press, 2023

One of the simple pleasures of science fiction is the possibility of escapism—into another reality, galaxy, or dimension beyond our reach. In the vibrant imagination of Yuri Herrera, however, abandoning the rules of our world allows for a speculative fiction that unites fantasy with lucid reflections on contemporary culture, experimenting with the bounds of genre to create something uniquely Herreran. The twenty stories that comprise Ten Planets, astutely translated by Lisa Dillman, combine the philosophical musings of Borges with a characteristic humour and warmth, inviting us to explore the twenty-first century and beyond.

From a house that plays tricks on its inhabitants to a bacterium that gains consciousness in an unsuspecting Englishman’s gut, Herrera’s imagination works on scales both large and infinitesimally small. The stories cover distances ranging the interplanetary and the interpersonal while retaining a sense of warmth and wonder at the world, expanding beyond genre conventions with a wry humour that packs a surprising punch. Dillman, in an insightful translator’s note, reflects on her personal reservations towards science fiction until she read the works of Octavia E. Butler, within which she saw how science fiction can shake off the coolness of rationality by turning its attention to very human problems, the ones we experience on a day-to-day basis. Herrera’s work is exemplary of the best of the genre in that sense, joining Butler, Ursula K. Le Guin, and others in his ability to imagine a dazzling array of worlds that each speak to our contemporary anxieties—from technological surveillance in ‘The Objects’ and the absurdity of the terms and conditions tick-box in ‘Warning’, to real stories of alienation and societal marginalisation in ‘The Objects’ (two stories bear the same name—because why not be playful?). READ MORE…