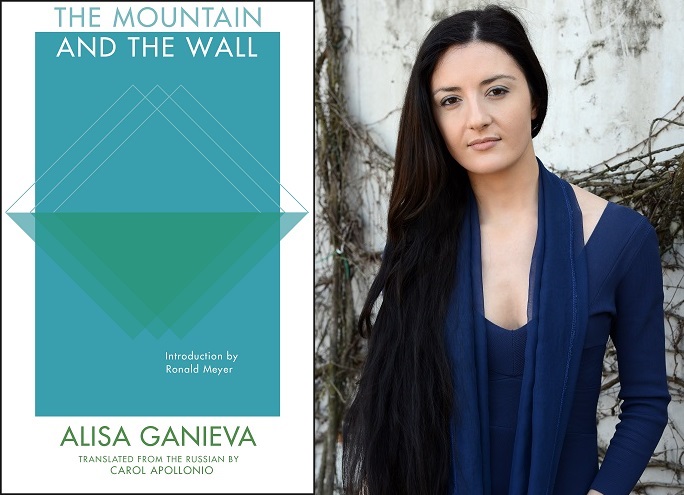

Last month, Alisa Ganieva was in Iowa City to teach global literature in English and the Russian-language workshop of the Russia-Arabic session of Between the Lines, a summer program for writers between the ages of 16 and 19 who spend two weeks in shared cultural and artistic dialogue about the literary traditions of their home countries. I sat down with Alisa to discuss her rise to literary fame and the new translation of her novel, The Mountain and the Wall, out this month with Deep Vellum Publishing.

At 24, you won the prestigious Russian literary Debut Prize of 2009 for your novella, Salaam, Dalgat!, which you wrote under a male nom-de-plume. How did you choose “Gulla Khirachev” for your pseudonym?

My goal was to hint those from Dagestan that I’m not a real author. That’s why I took a real name, “Gulla,” which means “bullet” in my mother tongue—in Avar language—but has not been used for many years. I found out there is actually an old man called Gulla, but he might be the only man with this name. So when my Gulla Khirachev appeared, many of those in Dagestan—journalists and writers—guessed that it must be a pseudonym, and they began trying to find out who it was. They guessed there must be a person, a young man, who lives in Makhachkala, since he knows it so well. They argued with each other and named different candidates, but always missed.

So you meant for the name “Gulla Khirachev” to be transparent as a pseudonym?

Yes, so the name means “bullet,” and the lexical root of this surname means “darling” in my native language. So it’s something piercing, but at the same time, it’s something . . . nonaggressive. READ MORE…