Now in its fifth year, this rebooted annual award for translated literature deserves a serious look. How does its newly released longlist compare to the Booker International counterpart?

Unlike its Booker International counterpart, works from European languages dominated, continuing the trend from previous years. Previous winner (and frequent Asymptote contributor) Yoko Tawada’s Scattered All Over the Earth was one of the only two titles from Asia.

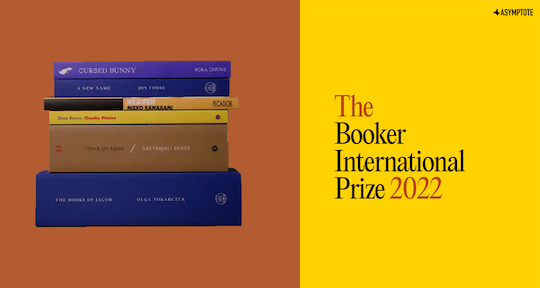

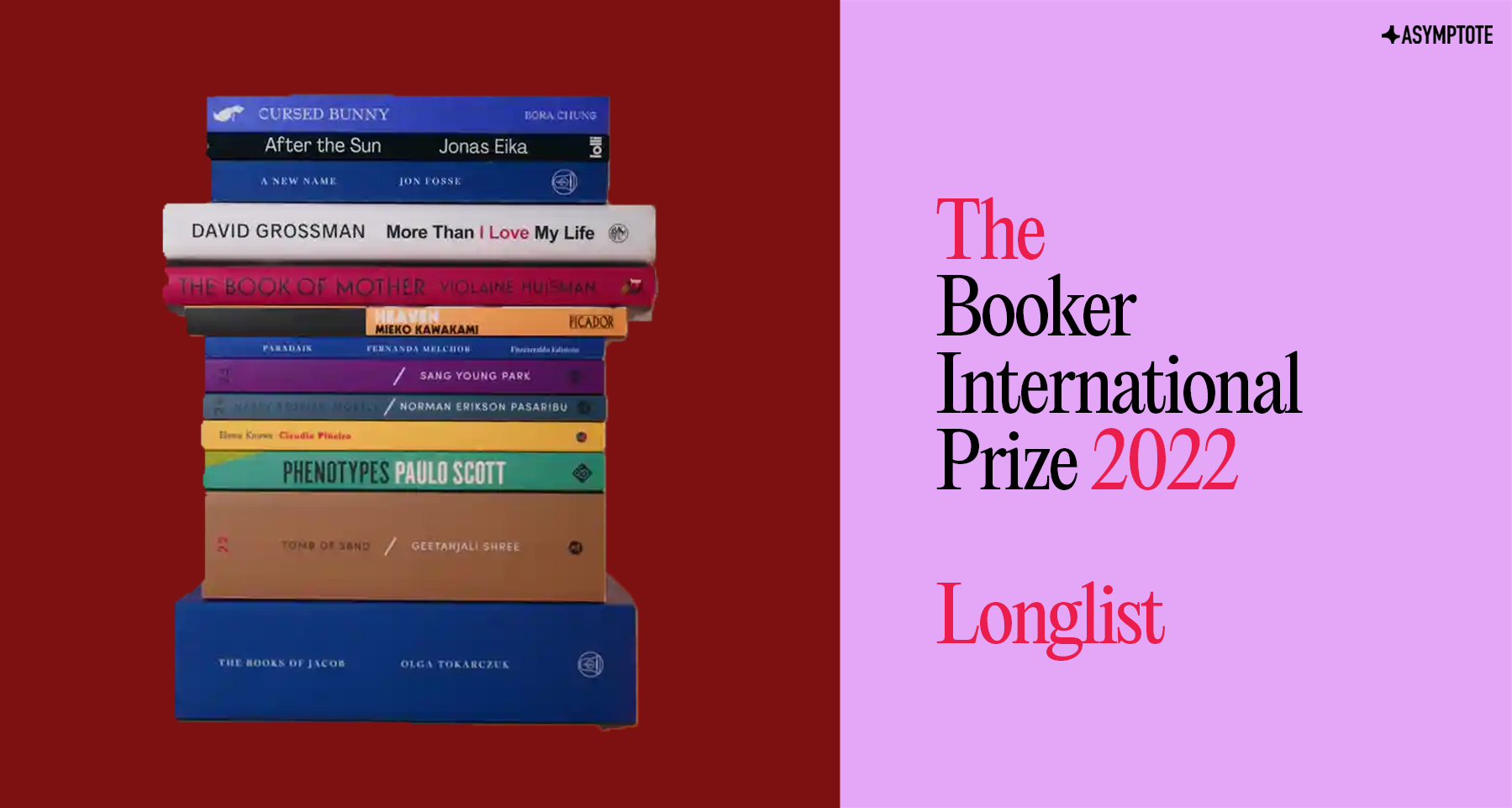

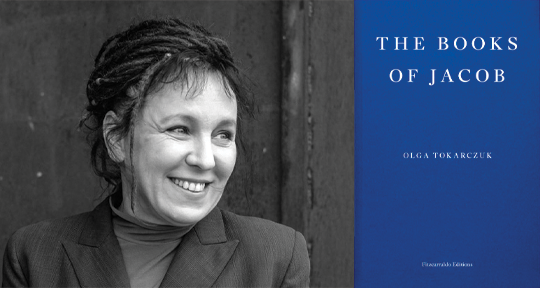

As with the 2020 selections, only one title appeared in both the Booker International and the National Book Award longlists, and it was an Olga Tokarczuk novel translated by Jennifer Croft. We hope it will be third-time lucky for this illustrious duo!

Order a copy of Olga Tokarczuk’s The Books of Jacob, translated from the Polish by Jennifer Croft.

New Directions is the only publisher to have two titles on the longlist. Aside from Yoko Tawada’s Scattered All Over the Earth, Olga Ravn’s The Employees, which our Criticism Editor Barbara Halla chose as her clear winner from last year’s Booker International longlist, is also nominated.

Incidentally, Aitken, who is the only longlisted translator to ever be nominated for his work on different authors, was interviewed in our pages last year. This year, we sat down with Mónica Ojeda, whom interviewer Rose Bialer calls “one of the most powerful and provocative voices in Latin American literature today.” Her Jawbone made the cut:

Order a copy of Mónica Ojeda’s Jawbone, translated from the Spanish by Sarah Booker.

We hope we’ve whetted your appetite with these selections. Take a look at the full longlist here! Oh, and by the way, we may receive a small commission for your purchase(s), which will go toward supporting our advocacy for a more inclusive world literature. Other ways to sustain our mission include signing up as a masthead member, or joining our Book Club!