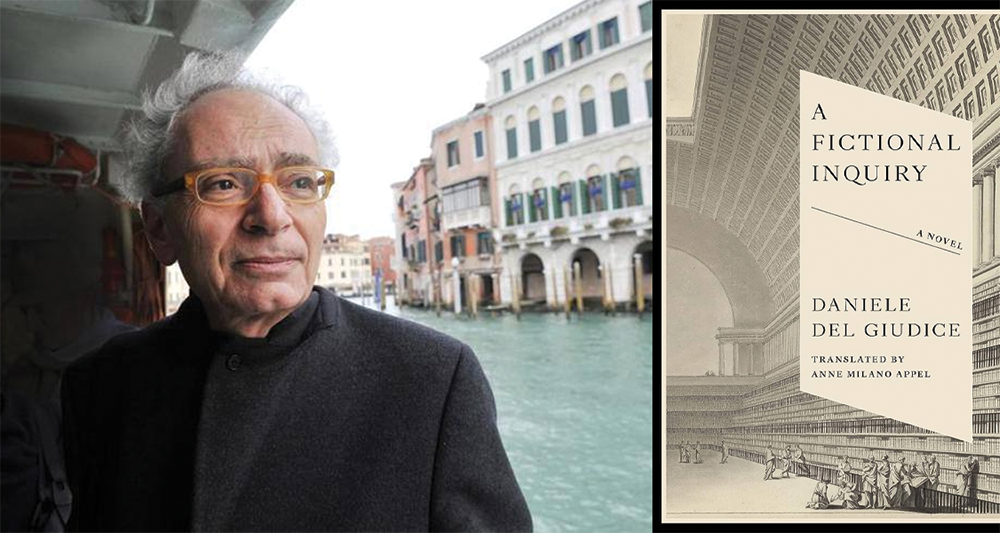

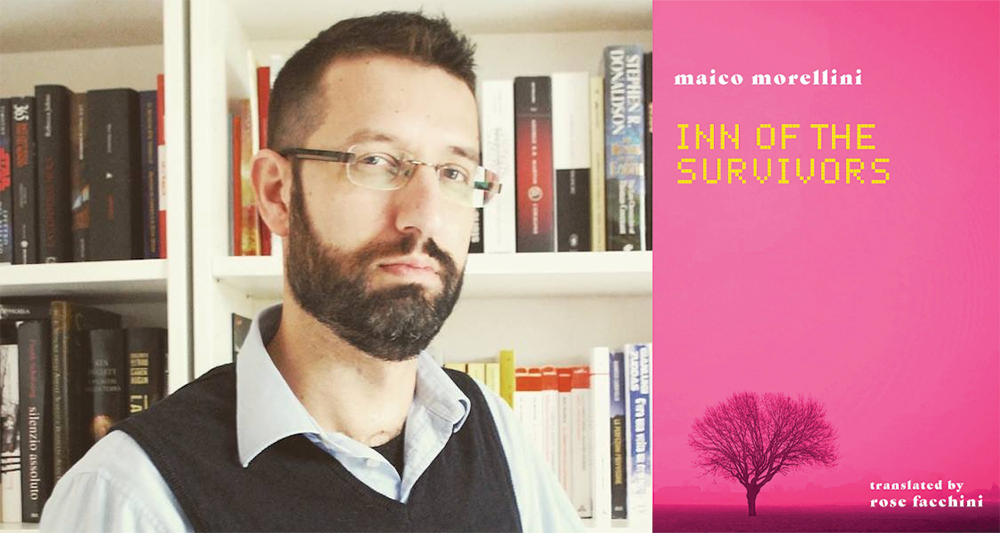

A Fictional Inquiry by Daniele Del Giudice, translated from the Italian by Anne Milano Appel, New Vessel Press, 2025

A Fictional Inquiry, Daniele Del Giudice’s first novel, is called Lo Stadio di Wimbledon (Wimbledon Stadium) in its original Italian—a reference to the end, when the protagonist journeys to Wimbledon to finish his, as translator Anne Milano Appel puts it, “inquiry.” The English title is clever; it places the conundrum of Del Giudice’s story right on the cover.

The titular inquiry is regarding the Triestean writer Roberto Bazlen, whose novels were published posthumously. The unnamed protagonist of A Fictional Inquiry travels first to Trieste and then to London, trying to understand why Bazlen did not or could not write while he was alive: “‘How did he hit upon the fact of not writing?’ I ask. ‘I mean the fact that he only wrote in private?’” Obviously, this inquiry concerns a writer of fiction, but it is not solely a question about what it means to write fiction; in a double meaning, the man’s inquiry is itself fictional, tossed out to the reader to cover up the protagonist’s (or Del Giudice’s) other, hidden, purpose.

This character arrives in Trieste with the supposed goal of interviewing Bazlen’s surviving friends and colleagues. He claims, during these encounters, to be gathering information in order to figure out why Bazlen never revealed himself as a writer, and as a result, these conversations map out his subject’s literary life. For some reason, however, the man is continually uninterested in the conversations he’s having. While speaking to a poet in her hospital room, he thinks: “I don’t care to listen to anymore; I want to leave, but I’m anxious about the formalities.” Before and during other meetings, he is just as hesitant. When asked if he is available to see a person of interest on that day, he responds: “Yes of course,” even while admitting to us that: “Truthfully I don’t know if I want to.” READ MORE…