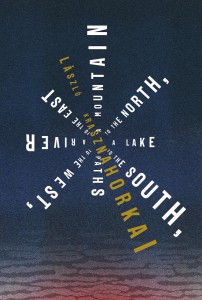

You carried me in your arms for years

Pine cone slivers lay on the bottom of the dried up riverbed, covering it like a rug woven from knots the size of a baby’s fist, but if I managed to shift perspectives, and I didn’t even have to squint my eyes to be able to do so, then I could see from the imagined altitude of a drone camera that this section of the National Blue Trail is in reality a battlefield, the space after a winning or losing combat, it doesn’t matter which, there lay the pine cone corpses, victims, then with time heroes, but I couldn’t keep playing with perspectives, we wandered on, it was already questionable what I was staring at for so long and I didn’t want to ruin the afternoon, because we had just emerged from the first challenge of our budding love, the kitten that had joined us next to a forest ranger’s loft, and it really was lovely, gentle and vulnerable, and you were set on bringing it home, but there was no such thing as home, you still lived in a studio apartment on the outskirts of Miskolc, while I was once again sleeping on the couch of a friend, where I always end up when my life comes off its hinges, or to put it more simply, when I’m in trouble, that palatine building and the windy corridor of the quay in Újpest being the Golgotha for me, so where could the ranger’s stolen kitten have come home to, but you had dug your heels in, you thought that the forest, destiny, or the Creator himself had sent us that puny animal, “we can’t leave it behind” you kept saying, while I kept pointing at the ranger’s wallpapered home, saying that maybe a grandchild, a loving little girl comes here to pet it each afternoon, and of course I was just looking for excuses, because I couldn’t have brought cat litter to my friend’s apartment, but with the image of a crying child I surprised even myself, and I was moved by how creative and empathetic I was being, but you couldn’t believe that I didn’t feel that it wasn’t just a kitten, but a challenge, a question, a deep dive of an interview, and God was curious about us, you were so sure that this animal had been born because of us, and we had to bring it home, it couldn’t be fateless, an orphan, and I had finally played my ace as a last resort, that it would be stealing, after which you kept walking in silent despondence in the riverbed, like someone who’d lost something, like someone who’d miscarried, and in the first house of Óbánya, in the old post office’s courtyard, matted horses were eating grass, the water in their buckets ebbing, at that time you were still going horse riding to the mountain, you weren’t afraid to sit on a horse, you sought the saddle, and I hadn’t been afraid either, although I’m always full of pregnant suspicions, I didn’t think up until the pine cone battlefield that God had challenged us with that kitten, in reality I was happy to settle for the small things, for example the fact that I finally lived and existed in a moment without wishing to be elsewhere, at that point I had been surrounded by lies for close to a decade, in a constant state of remorse, and I always wanted to be somewhere different, so it was a cellularly new experience to be able to exist entirely there with you, where I’d chosen to be, and no matter how hard I try to remember it differently, that kitten hadn’t been a bad omen to me even past the pine cones, or at least not any worse than the pine cone battlefield in-between the river’s pebble-cliffs, after all, there was something ominous about that too, and there, as I surveyed the expanded land from high up I shuddered, that it was too much, that something bad was to follow, we were too happy and the binding balance of good and bad was missing, and the riverbed was beginning to look like a model of a movie being filmed, and our eyes were level with the slowly receding aerial shot, two thirsty people drunk on love, who, in the village’s only pub, when they slotted the first coin into the vinyl jukebox and sat down next to the crackling tiled stove, already knew that they were going to live out their lives together, which was guaranteed by Attila Pataki’s sublime voice, you pressed the button and the bartender piped up, “forty-three,” and took a sip of his beer, “Edda blues,” and I couldn’t believe that you’d chosen the band Edda, you hadn’t yet known that you were going to leave the city, there was no subtle metaphor in that musty old hit, there was only us, and the regulars, and with us a naked, impudent happiness, that in an abandoned village’s only pub we’d be listening to Edda on a jukebox, which can’t get any better, we were choking on laughter, and then silence, silence again, and I thought to myself in the bathroom, with my eyes trained on the endless depth of the urinal, that I needed to change, that I couldn’t continue to expect the worst during the happiest moments, that it shouldn’t be a problem when something fits so perfectly, or when for once it happens so easily, like a long awaited resolution; so we picked our way through the riverbed towards the empty village, the old church of Óbánya gleaming like a crone dressed in her Sunday best, and I had already forgotten or wanted to forget the kitten, but I could still see a captivating sadness in your eyes, and I realised only years later, once I’d pricked your belly full of injections, and once they’d put me in that mesh mask of historic horrors for the first time, wheeling me into the machine under the burn of radiation, I realised only then that all our hopes for a child were gone, and just how naive I’d been, but by then I was only envious of our necessarily and rightfully infantile hopes of the past, we walked on in the pine cone pellets, in the view of a seriously thought-out, long and happy life, knotted sounds floating from the mountain, our shoes sticky with resin, and it didn’t even occurr to me that God could’ve shaken his head when we left that kitten, shaken it and turned his eyes from us for years, and now I know that it was the last time we’d been childishly and cluelessly untouchable, and every subsequent explanation and over-thought suspicion about pine cone corpses and kittens had been in vain, we wouldn’t have believed it truly and deeply even if the Prophet himself told us, even if he appeared on our way home and sat down next to us at the small pub, slotting a coin into the jukebox himself and pressing forty-four, and Slamó would’ve thundered you carried me in your arms for years, and I was a prisoner of your will in vain, because if Jesus himself had revealed it under the truth of that song, we still wouldn’t have believed that something wouldn’t work for us, something all-important, not the way we would want it, not the way it should be, nor, as people would whisper about it in the stairwell, the proper way.