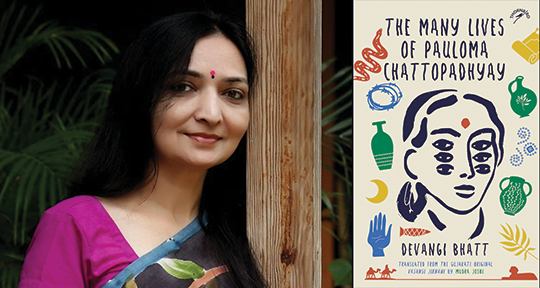

The Many Lives of Pauloma Chattopadhyay by Devangi Bhatt, translated from the Gujarati by Mudra Joshi, Niyogi Books, 2024

In The Many Lives of Pauloma Chattopadhyay, Devangi Bhatt’s novel of fantastic realism, the extraordinary is prefaced by a scenario of extreme normalcy. In Kolkata, Pauloma Chattopadhyay lives out her days as an ordinary middle-aged housewife. Her husband, Nikhil babu, is a civil servant and a man of a few words, set in his routine. Sharing their house are two sons and their families; there is a daughter too, but she is married and hence resides elsewhere. Theirs is a standard joint family and Pauloma is unquestionably the matriarch of the household, but it would be hard to say that she has any power to go along with that position—and even if she did, she is not one to exercise it. All things go about in harmony in house no. 11 with the well-practised dailiness of domesticity, and from the beginning, Bhatt makes it clear that her movements are not curtailed, and nor does she live in a state of unhappiness:

Pauloma is a vivacious woman with an abundant love for life. She likes gossiping with the neighbours, bargaining with the saree seller, watching Bengali plays with her daughters-in-law, and feeding her grandkids sondesh. Though Nikhil babu and Pauloma are very different, it can be safely said that their world provides a sense of stability. Everything has been well for a long time, and there have been no problems.

Stability, however, tends to get stale after a point in time, and even more so for a housewife whose life mostly takes place within four walls. While Pauloma is not exactly crushed by the mundanity, she nevertheless recognises it: “But… but sometimes a strange thought crosses Pauloma’s mind as she sits by the window, rubbing oil on her scalp. . . . As she turns the shell bangle on her wrist, she thinks that life shouldn’t be like a straight line without any exciting deviations.” These short moments are akin to revelation, brief ripples on a still body of water, and it is this feeling of the past slipping through her fingers, of the transience of her life, that sends her to the storeroom in search for her late mother-in-law’s large storage vessels—which have been gathering dust and are set to be sold. On a whim, she climbs into one of them, only to be immediately pulled inwards and magically transported. READ MORE…