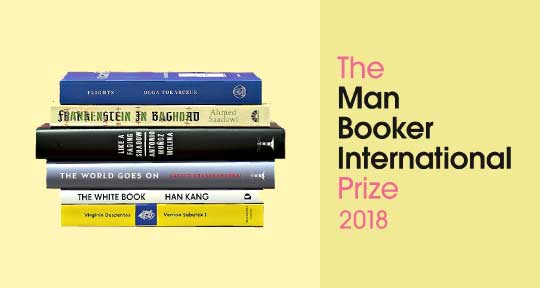

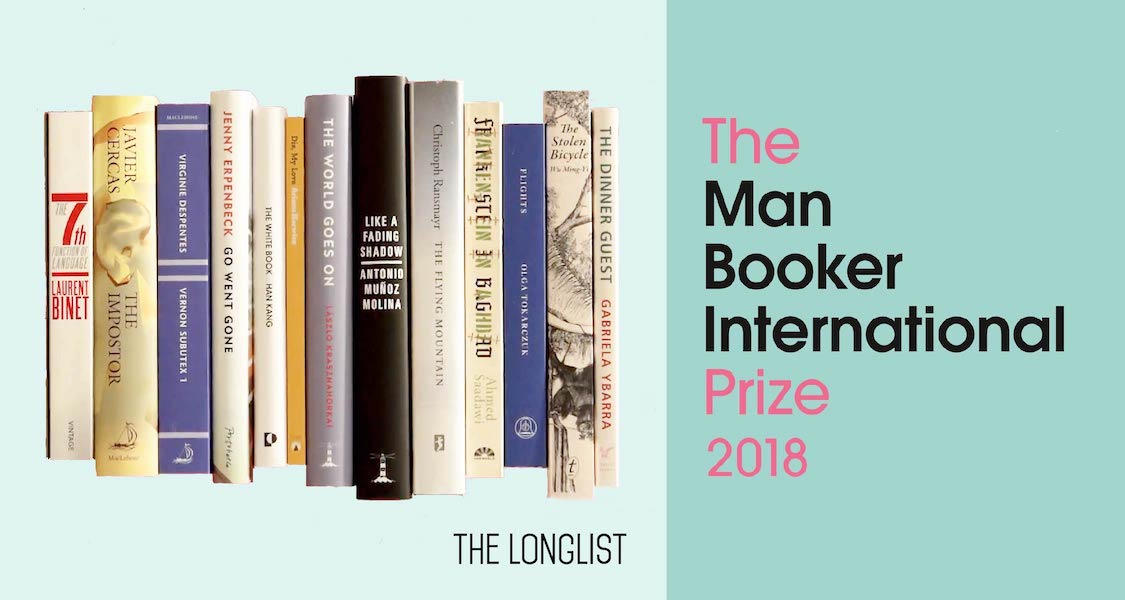

“A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a re-reader,” Vladimir Nabokov reminds us in his article “Good Readers and Good Writers”. There are so many books in this world, and unless your life revolves solely around books, it might be hard to be widely read and an active re-reader. Attaining this level of perfection that Nabokov describes is impossible, but the idea of re-reading as a tool to better understanding the value of a book underpins the philosophy of the Man Booker Prize International’s judging panel since its inception.

Language: French

Section Editors’ Highlights: Spring 2018

Our Section Editors pick their favorite pieces from the Spring 2018 issue!

The brand new Spring 2018 issue of Asymptote Journal is almost one week old and we are still enjoying this diverse set of writing. Today, our section editors share highlights from their respective sections.

The phrase “Once upon an animal” has been circulating in me for months, ever since I first read Brent Armendinger’s translations of the Argentine poet Néstor Perlongher. The familiar fairy tale opening, ”Once upon a . . .” asks one to think of a moment, distant, in time, when such and such happened—happened miraculously or cruelly and from which one might take (dis)comfort or knowledge of some, perhaps universal, human frailty or courage. But Perlongher/Armendinger replace “time” with “animal”—a body. Against time, in its very absence, we’re asked to look at this body, which is in anguish, now. Perhaps now too is in anguish.

I can’t read Spanish, but the translation suggests a poetry of complex syntactical structures and lexical shock:

Once upon an animal fugitive and fossil, but its felonies

betrayed the same sense of petals

in whose gums it stank, tangled, the anguish

impaled, like a young invader

A feat of translation, no doubt. Armendinger writes that “this intensely embodied and unapologetically queer language” is what drew him to Perlongher, and now we too are drawn in.

Perlongher was a founder of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual Argentino, agitated against the military dictatorship, and, as an anthropologist, wrote about sex workers, and gay and transgender subcultures. All this—writing, work, and play—was perhaps yet another way of saying: “Be still, death:”; “in the steam of that / eruption: ruptured play, rose / the lamé.”

—Aditi Machado, Poetry Editor

In Conversation: Stephanie Smee

As her translator, I have had the opportunity to sit quietly with her as she pondered the inhumanity of the Nazi regime when she was forced to flee

The Spring 2018 issue launch is just around the corner (stay tuned…) and it is full of amazing writing from around the world. This season we approach the question of family. Texts explore exiles, adulterers, and a levitating aspirin in our Korean Fiction Feature, headlined by acclaimed filmmaker Lee Chang-dong. Amid exciting new writing and art from twenty-nine countries, gathering together such literary stars as Mario Vargas Llosa and Robert Walser, discover “tiny shards” of childhood on the verge of experience as remembered by Jon Fosse—a giant of Norwegian letters in his own right—or not remembered by Brazilian author Jacques Fux à la Joe Brainard.

Although “unhappiness is other people,” according to Dubravka Ugrešić, we’re just as likely to be imprisoned in our own family, a predicament brought to light in Dylan Suher’s review of Eileen Chang’s Little Reunions. In a generously personal essay, Ottilie Mulzet reveals how she turned to Gábor Schein’s “father-novel” to unlock the secret of her intransigent birth mother, whose refusal to speak to her had “stood in [Mulzet’s] life like a monumental cliff.” Schein’s poetry also graces this issue, and in a timely echo of Spring and past horrors, he takes up the refrain of Dayeinu of the Passover Haggadah—it would have been enough for us: “Enough, if you or I still / hoped for something. Enough, if we forgot to remember…”

For some, family remains a hall of mirrors, leaving the outlook bleak for human brother- and sisterhood: “My path doesn’t lead to you. Your path doesn’t lead to me,” writes the Libyan poet Ashur Etwebi. At times, language cuts as deep as our common mortality, that kinship beyond all social roles, as in the poignant drama, The Last Scene. Echoing the resignation of Alain Foix’s death-row prisoner, poet Esther Tellermann laments, “breathe me / sister in death.” Others, like Cairo-based artist Amira Hanafi, strive to knit together connections between strangers. Her recently concluded installation, A Dictionary of the Revolution, deployed a vocabulary box of 160 words to generate conversations with more than two hundred people across Egypt.

As a special treat for our blog readers, we bring you a special interview conducted with this new issue in mind. As she prepared her enlightening criticism, Brigette Manion sat down with translator Stephanie Smee to talk about her translation of No Place to Lay One’s Head by Françoise Frenkel. As Brigette explains in her review, “No Place to Lay One’s Head looks back over Frenkel’s life, from her youth as a bibliophile and her establishment of a bookstore in Berlin, to her journey across France and final passage into Switzerland. Frenkel presents a story of survival and resilience dedicated in her foreword to the memory of the ‘MEN AND WOMEN OF GOOD WILL’ who, with great courage and often at considerable risk to their own lives, helped and inspired her along the journey.” Happy reading!

Brigette Manion (BM): How did you first come across Françoise Frenkel’s memoir, and do you remember your initial response to it?

Stephanie Smee (SS): I first came across Frenkel’s memoir after reading a review in Lire magazine. I had the good fortune to be in Paris when I read it for the first time, and many of the images she described, particularly of her early years in Paris, felt incredibly poignant. Perhaps my response to her very moving story was tempered by that. I also found her descriptions of different places so detailed and lyrical that they evoked a visceral response in me. I remember, too, being terribly affected by the immediacy of her writing, a characteristic of her memoir which truly sets it apart, in my view, from many other memoirs that are often written several years after the events that are the subject of the work.

Dispatch: Bologna Children’s Book Fair

Human representation has acquired a renewed central position, previously abdicated in favor of animals and such.

Four days of intense work within a whirlwind of smiling people who convene here year after year like old friends, while at the same time looking for, proposing, and selling stories that will hopefully enchant today’s children. It is the Bologna Children’s Book Fair, the most important event for children’s literature in the world, taking place every year in Italy. This year’s edition ended almost three weeks ago. From March 26 to 29, seventy-seven countries and regions, 1,390 exhibitors, and 27,642 publishing professionals gathered in a bustle of illustrators, authors, publishers, agents, translators, booksellers, and journalists.

Walking through the stands, one can run into tidy lines of novice illustrators who, nervous and creatively dressed, are waiting to exhibit the works they clutch in their hands. One could also bump into celebrations of publishing houses’ “birthdays” or other anniversaries, while inside the stands, agents exhibit new books’ plates before the publishers’ and journalists’ attentive eyes. Just around the corner, interesting educational events are taking place while trembling crowds of aficionados await to meet their favorite artists in flesh and blood. The air is international: in just a few steps one can walk from the forests of Northern Europe to the colossal American stands, to the elegant French stalls. From there you can meet the Japanese artist who collects pebbles and encloses them in personalized books, along with artists, writers and editors from Iran, Chile, Africa and India.

These four days are a vortex of fatigue, legs grinding mile after mile among the stands and eyes taking in an extraordinary amount of illustrations, images, and stories. Once back home, it is necessary to take a few days to detox and reflect upon what one has lovingly noted.

In Conversation: Naivo and Allison Charette on Beyond the Rice Fields

"Each language has its own tolerance to gravity—or to weightlessness."

The Best Translated Book Awards longlist was announced yesterday, and it included Naivo’s singular novel, Beyond the Rice Fields. The first novel from Madagascar to be translated into English (from the French by Allison Charette), it comprises a narrative that unfolds like palm fronds. Set in 19th-century Madagascar, the narrative stem follows the evolving relationship between Tsito, a boy sold as a slave to a trader, Rado, and the trader’s daughter, Fara.

Naivo (the pen name of Naivoharisoa Patrick Ramamonjisoa), who is also a journalist, pairs a reporter’s unflinching approach to storytelling with a poetic style and distinctive orality that stems from the Malagasy literary tradition. The story moves from the Madagascan highlands through the midlands to the country’s capital, Antananarivo, the ‘City of Thousands’, and even to England. Through it all, the concept of “frontiers”—between traditions, social classes, countries, and historical moments—is posed as a question: how do we close the interstices between beliefs, and the gulfs between each other?

In Beyond the Rice Fields, Madagascar’s brutal history is revealed through individuals whose journey, relationship and thoughts are as important as the larger historical narrative, which sweeps them along, but is never in danger of sweeping over their story. In one instance, Fara’s grandmother’s tales dissolve into the outcome of the primary narrative. Here, the past is not viewed as finished, nor the present as momentary; rather, Naivo shows that the past is still with us, and that we are part of the past. This is evident even in his phrasing: the “evil red crickets” of an invading tribe; the juxtaposition of terms like “judge” and “earth husbands” within the context of a trial-by-poison. Although Naivo paints the march of time as implacably brutal, his is not a moral nor critical view of history; crimes are committed—in the name of both tradition and progress—but what is more important is what endures: love, nation, storytelling.

Asymptote spoke to Naivo and Charette about inspiration, the process of writing and translation, and the literary scene in Madagascar.

Alice Inggs: Allison, How did you come across Beyond the Rice Fields and how did you come to translate it?

Allison M. Charette: Back in 2013, I randomly found out that no novels from Madagascar had ever been translated into English. I decided to help fix that, and ended up traveling there the next year to meet authors, learn the culture, and acquire books. Beyond the Rice Fields was one of the thirty-some-odd books I brought home, but it was a particularly good one: it had been recommended to me by a couple of booksellers and several authors, who all called it one of the best literary debuts they’d ever seen. I read it and loved it, so it was one of the top 5 novels that I wanted to start shopping around to American publishers. I was fortunate enough to receive a PEN/Heim grant for it in 2015, which is how Restless got interested. And the rest, as they say . . .

Weekly Dispatches from the Frontlines of World Literature

Our weekly roundup of literary news brings us to Morocco, Hong Kong, and the United States.

We are back with the latest from around the world! This week we hear about Morocco, Hong Kong, and the United States. Enjoy!

Hodna Nuernberg, Editor-at-Large, reporting from Morocco

Some seven hundred exhibitors from Morocco and around the world descended on Casablanca for the Salon international de l’edition et du livre, which took place from February 9-18. Half open-air souk (rumor had it that one of the ambulatory vendors went so far as to offer women’s panties for sale!), half oasis of high culture, the book fair counted over 125,000 titles from forty-five different countries. Egypt, this year’s guest of honor, accounted for nearly fifteen percent of the titles on offer alone, and managed to ruffle more than a few feathers when an Egyptian publisher was allegedly caught displaying a book (A Brief History of Africa) whose cover featured a map of the continent depicting a “mutilated” Morocco—the disputed territory of the Western Sahara appearing as an independent nation under the Polisario flag. The presence of the book was firmly denied by the Ministry of Culture.

On Surtitles and Simultaneities: Reflections on the German Theatre Scene

No longer before, behind, or above the original, with surtitles, the translation is now parallel or simultaneous to it.

Lars Eidinger, playing Richard III, huskily whispers some German lines of Shakespeare into an amplifier, furtively glances up to the English surtitles, and spins round to berate a coughing audience member in French. This is theatre in a truly globalised arts scene. But the multilingual nature of many recent productions not only reflects the realities of our contemporary social conditions. It raises fundamental questions about the nature and role of the linguistic mediation of culture today.

What’s New with the Crew? A Monthly Update

Stay up-to-date with the literary accomplishments of the wonderful Asymptote team!

Contributing Editor Aamer Hussein participated in the Sixth Annual Lahore Literary Festival on 24 February, 2018 at the Alhamra Arts Center.

Communications Manager Alexander Dickow won a PEN/Heim grant for his translation of Sylvie Kandé’s Neverending Quest for the Other Shore: An Epic in Three Cantos.

Drama Editor Caridad Svich published an article entitled Six Hundred and Ninety-Two Million: On Art, Ethics, and Activism on HowlRound. Her play, An Acorn, recently opened at Trinity Repertory Company in Providence, Rhode Island.

Meet the Publisher: Groundwood Books’ Patricia Aldana on Children’s Literature in Translation

"The key—to have children be so entranced by the books they read that they will be a reader for life."

Groundwood Books is a Toronto-based publisher of children’s and young adult literature. The press was founded by Patricia Aldana in 1978 and almost from the start has been publishing Canadian literature alongside titles from around the world in translation. Groundwood’s catalogue includes books from Egypt, Mexico, and Mongolia, to name a few, and the press is particularly interested in publishing marginalized and underrepresented voices. Though Aldana sold Groundwood to House of Anansi Press in 2012, she remains active in the area of children’s literature. She is currently president of the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY) foundation and collaborates with the China Children’s Press and Publications Group, where she is responsible for bringing international literature to Chinese children. In an interview that took place in Buenos Aires during the TYPA Foundation’s workshop on translating literature for children and young adults, Aldana spoke with Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for Argentina, Sarah Moses, about the qualities she looks for in books for children and the challenges of translating for young readers.

Sarah Moses (SM): When did Groundwood Books begin publishing children’s and young adult literature in translation?

Patricia Aldana (PA): Quite early, by 1981, I started doing translations of books in French from Québec. There were subsidies for translation from the Canada Council, which made it easier—especially novels. I was also going to Bologna and selling rights, and there I started finding books from other languages that were interesting to translate.

The Canadian market was quite healthy at that time and you could bring in books from other countries. But in 1992 provincial governments started to close down school libraries which affected the entire ecosystem of the Canadian market and we had to go into the U.S. market directly and publish books there ourselves. A lot of our authors were known in the States because we had sold rights to them, to compete with the U.S. giants and to differentiate ourselves from them as by that point they had virtually stopped translating anything—we seized the opportunity to publish translations for a much bigger market. The Canadian market had deteriorated to such a point by then that it couldn’t really justify publishing a translation—other than of a Canadian author from Québec.

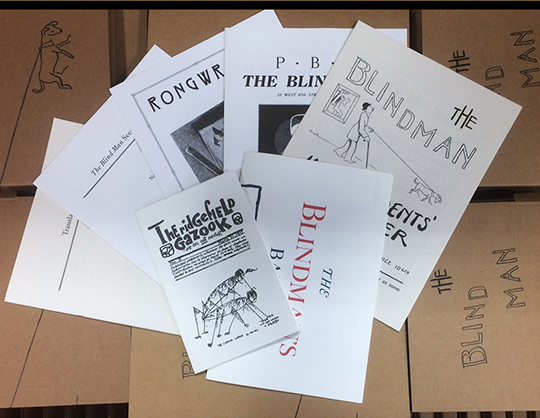

In Review: The Blind Man

That is, beyond the words themselves, the textuality of the work does justice to the playfully serious attitude of the original.

The Blind Man: 100th Anniversary Facsimile Edition edited by Marcel Duchamp, Henri-Pierre Roché, and Beatrice Wood (Ugly Duckling Press, 2017). Translated from the French by Elizabeth Zuba.

With all of the uncertainties of the current geopolitical climate, it is fitting that in the beginning of 2018 we turn our attention to the past for historical context and a better sense of the wider context of recent events. In Sophie Seita’s insightful essay that accompanies Ugly Duckling Presse’s one hundredth anniversary facsimile collection of Dadaist zines and ephemera associated with The Blind Man (referred to in Hyperallergic as “a trove of Dadaist fun”), the critic encourages readers to understand Ugly Duckling’s reissue of these magazines precisely within their broader context, with “a facsimile reprint like ours attempt[ing] to recreate the original print context and…forg[ing] new dialogues with contemporary literary and artistic communities today.” Of course, in 1917, Europe was in the throes of World War I, and the artistic movement which the The Blind Man is most closely associated, Dada, is frequently held up as “an artistic revolt and protest against traditional beliefs of a pro-war society.” Rather than simply the considerable achievement of reproducing a one hundred-year-old, self-consciously cheeky avant-garde magazine in a beautiful collector’s edition, I’m keenly interested in the dialogues Seita claims the re-edition seeks to cultivate, meditating as much on what The Blind Man tells us about the present as it tells us about the past. In my view, Ugly Duckling more than delivers.

Translation Tuesday: “The Results” by Bernard Comment

"Jealousy is always a weakness, an uncertainty, a lack of confidence, every other person is a competitor, a threat."

On a check-up at a health clinic, a father and husband’s interactions with doctors are punctuated by reminiscences of love and lust for his wife. Gradually, we learn of a chilling act of violence, which leads the protagonist to a twisted reckoning with his mental and physical condition.

It’s cold. A cold that bores into you, that hasn’t let up for days, despite the big woollen jumper I never take off, even at night. Carlo tells me I should take it off for sleeping, and wrap myself up well in the blankets, so that when I get up I would add a garment to make up for the change in temperature, but one evening I tried this and my teeth chattered all night. The other men I see at lunchtime don’t seem to suffer, there’s even a guy who always walks around in a T-shirt, but admittedly he’s a burly fellow, well-padded against the cold.

The doctor made me go back to him this morning, after fasting, he wanted to do further tests, two whole syringes filled with blood, I asked to lie down because I’m always afraid of turning to look, and it’s much worse if you get to see it. The nurse smiled, although I couldn’t tell if it was from pity, sympathy, or scorn. She had difficulty finding the veins, it’s always the same, I begin to tense up, to sweat at the temples, I become dizzy and pale; when I was a teenager I passed out each time, and once I fell backwards and hit my head on a sink, was sent straight to hospital for a battery of tests, a lumbar puncture, and an idiot teacher spread it around that I’d taken an overdose, me who’s never touched the tiniest amount of an illegal substance, for fear of my reaction, and my scrupulous respect for the law.

When I had the first tests, eight months ago, the lady in the laboratory was very considerate, settling me into an armchair and telling me to look away, and to think of something pleasant; so I thought about the film I’d watched the night before, with Julie, her warm body, her breasts in my hands, her smell after making love. Then it was finished, and already I had a piece of cotton wool and then a sticking-plaster on top, whereas here everything is rougher, more brutal. I’ve been waiting for twenty minutes, standing in front of the grey door. They came to get me around six o’clock. Immediate appointment. Everything moved fast, then the iron door in the corridor clanged shut behind me, with a heavy ringing sound, and since then, nothing. The doctor must be on the telephone, I hear his voice at times, a powerful, raucous voice, but I don’t understand what he’s saying, the rooms are well insulated. I’d love to smoke a cigarette, it’s what I’ve been brooding about for a full five minutes, it’d do me good, would relax me, smoking a cigarette.

READ MORE…

Contributors:- Bernard Comment

, - Carolyne Lee

; Language: - French

; Place: - Switzerland

; Writer: - Bernard Comment

; Tags: - clinic

, - condition

, - family

, - french

, - health

, - hospital

, - love

, - lust

, - marriage

, - Short Story

, - Swiss