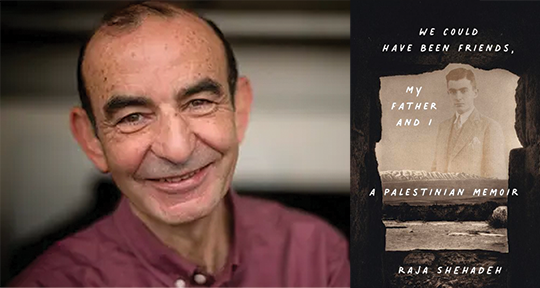

We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I: A Palestinian Memoir by Raja Shehadeh, Other Press, 2023

In Postcolonial Memoir in the Middle East (2012), Norbert Bugeja defines the memoirist as operating “within that representational chasm . . . in which the memoirist’s chosen interpretation of a space or preferred schema of memory come to be reconfigured against the received facts of traditional ideological geographies and vice-versa.” In the harrowing We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I: A Palestinian Memoir, Raja Shehadeh shows he is no exemption to this friction between fact and memory. A Ramallah-based human rights lawyer with several acclaimed memoirs (one received the 2008 Orwell Prize; another was adapted into a stage play) and scholarly essays (covering topics from international law to theatre criticism) to his name, Shehadeh is a cosmopolitan, peripatetic writer and addresses the topic of his personal history and homeland with wide-ranging expertise. According to Jonathan Cook in Disappearing Palestine: Israel’s Experiments in Human Despair (2008), Shehadeh “is perhaps the most knowledgeable critic of Israel’s labyrinth of legislation in the occupied territories.” In addition to enacting activism through his writing, he also founded al-Haq in the 1970s—a Palestinian organization at the frontlines in peace negotiations and in providing legal aid to Palestinians.

In We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I, his eleventh book of non-fiction, Shehadeh foregrounds the Nakba—the catastrophic aftermath of the 1948 Palestinian war. But a better appreciation of his works necessarily invites a discussion on the milieu of where he is writing from—both ethnopolitically and aesthetically. Ethnopolitically, the memoir centres the land dispossession, drone warfare, and strategic erasure of Palestinians perpetrated by the Israeli military government—as well as the treacheries committed by Palestine’s former coloniser, the Ingleez, Britain, and even neighbouring nations like Jordan and the League of Arab States. Aesthetically, on the other hand, the writing evokes other articles of “resistance literature,” such as those concerning Partition or occupation, as well as the larger body of Arab political essays and political memoirs that permeates Shehadeh’s œuvre: his powerful storytelling emanates from the kind of clearsighted prose afforded by forthright reportage.

Conor McCarthy favourably compared Shehadeh to Edward Said as being “more directly political,” evidently a departure from show don’t tell (a hackneyed chestnut propagated by workshop cultism because there should be, in descriptive writing, room to explain, to tell). Shehadeh takes advantage of the power in exposition even as he plays with form; the narration and the way the chapters are organised as somewhat non-linear and non-chronological, jumping from one particular time and place to another, but remain always guided by both reminiscence and research. READ MORE…