This month’s selections of newly translated world literature seem to revolve around the unknown, be it to uphold or dispel it: a Mexican short story collection explores its protagonists’ dark psyches while providing no easy answers, a piece of Polish reportage rediscovers lost voices on nineteenth- and twentieth-century immigrant experience in America, and a Brazilian novel hilariously tackles a group of friends’ exploits in almost unchartered digital territory during the nineties.

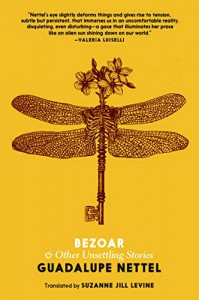

Bezoar: And Other Unsettling Stories by Guadalupe Nettel, translated from the Spanish by Suzanne Jill Levine, Seven Stories Press, 2020

Review by Samuel Kahler, Communications Director

Unusual as they may be, the strange and wistful short fictions in Guadalupe Nettel’s Bezoar: And Other Unsettling Stories are not only clever in their portrayal of human desire and obsession; they are often wise as well. Nettel, an acclaimed Mexican author, was named as one of the Bogotá 39 and is a recipient of the largest Spanish-language short story collection prize, the Premio de Narrativa Breve Ribera del Duero. Bezoar is her second collection of stories, published in the original Spanish in 2008 and now translated into English by Suzanne Jill Levine.

Over the course of the book, Nettel and her characters have something fresh to reveal about their unique obsessions and secrets (the stories are told from the first-person perspective). But at just over one hundred pages, Bezoar is an all-too-brief journey through the grey areas and dark recesses of hidden passions, lusts, and compulsions.

Depending on one’s subjective definition, the narrators of Bezoar might be considered everyday people who, at face value, live quiet, unremarkable lives: a photographer in Paris, a man strolling through Tokyo’s botanical gardens, a teenager on a summer vacation, and—yes—a voyeur here, a stalker there, and one supermodel under psychiatric supervision. While memorable and idiosyncratic, these are not outsized characters with grand schemes; instead, they look inward and act in near-singular pursuit of resolving psychological issues. Fittingly, their stories are intimate chamber pieces that delight in the details of unfulfilled needs and wants, emotional attachments and detachments, and traces of personal insight that at times reflect a broader general truth about human dissatisfaction. READ MORE…