These days, the reading world eagerly anticipates the Swedish Academy’s annual awarding of the Nobel Prize for Literature, placing bets and preparing stacks of shiny gold stickers, ready to be stamped on newly reprinted books. Yet the Prize, now over one hundred years old, has had many of its laureates fall into obscurity, either due to a seeming lack of contemporary resonance, or the changing priorities of the Academy itself. In this essay, we look towards the works of one such writer, whose pivotal titles perhaps deserve a revisit for their stylistic commitment, persistent human themes, and documentation of the times.

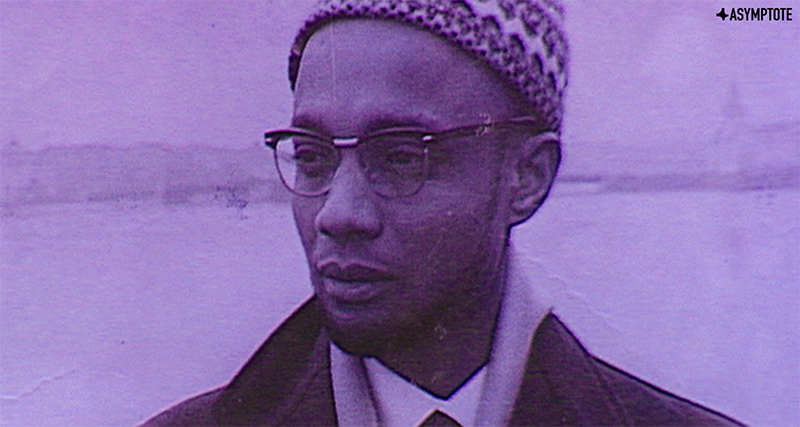

Władysław Reymont, Poland’s second Nobel Laureate, was born to the family Rejment in 1867; in 1892, when he was first published, he insisted on changing his name’s spelling (if not its pronunciation), in part, as Polish academic Kazimierz Wyka speculated, because of its closeness to the verb rejmentować: “to cuss” in certain Polish dialects. For some authors, this would be a humorous footnote in their biographies, but for Reymont, it proves an apt metaphor for his oeuvre. His major works—including, most famously, Ziema obiecana (The Promised Land) and Chłopi (The Peasants)—are beautiful and distinct depictions of nasty, earthy lives. Like curses disguised with respelling, they reconfigure their surprising, sometimes shocking base material, deriving elegant representations from the inelegant. Despite being drawn, like so many Polish intellectuals of his era, towards a vision of Polish nationhood that literature had to help create, Reymont opted to render Poland as a grimy, smoky, bloody place—but where he becomes intriguing, and what perhaps most compelled the Nobel Committee to award him the 1924 Prize in Literature, is when that focus on the bodily and the brutish becomes celebratory and even liberatory, for both its subjects and their nation.

Reymont was born into a Poland that was, by then, absent for decades. By 1867, the nation had been partitioned between Austria, Prussia, and Russia for nearly seventy years. Seemingly mirroring this fragmentary state, Reymont was a shoemaker, then an actor, then a linesman on the Warsaw-Vienna Railway, then a prospective candidate at a monastery, before he made his way to writing. Nonetheless (or perhaps because of his aimless decades), Reymont had established himself as a major figure in the Młoda Polska (Young Poland) movement by the end of the nineteenth century, primarily through his short fiction and travel narratives. The Young Poles—working across literature, music, and art—were neo-romantics, skeptics of the old world order that seemed to edge closer to collapse with each toppled European monarchy or imperial clash, and Reymont’s best-known works are no different. In Ziema obiecana, modernity is simply decried; in Chłopi, Reymont seeks a solution by turning inwards to Poland’s rural culture, timelessly isolated from modern concerns. In both works, we meet plenty of violence, gory detail, and literary profanity, but Reymont’s choice of subject for the latter novel reframes the grit in terms that the Nobel Committee registered as transcendental and universalist. READ MORE…