The impetus to read women is very similar to the desire to read the world; one does not necessarily do it out of a purely social cause—though that can hardly be argued against—but because the profound, intelligent curiosity that sustains the act of reading can only be validated by reading variously, probingly, and with an awareness of life as it is being lived now. Even as the world of letters is slowly ridding itself of entrenched biases and definitions, it remains an indisputable truth that the idea of being a woman in this world continues to throb with chaos and fragility, and increasing globalist awareness only reinforces the fact that womanhood remains replete with mystery, inquiry, and greatly variegating methods of approach.

To find the language that does justice to this experience of living—whether or not womanhood is the subject—requires a persevering intellect and originality that one finds in the greatest of minds. A reader does not pick up a work of translated literature to learn how being a woman is done in that part of the world, but to be allowed entrance into a vast, ridiculously under-explored, realm of humanity, whose inner workings often prove to be—as a result of challenges that must be overcome—intellectually complex, stylistically thrilling, and revolutionary in their uncoverings of human nature.

That is why I, for one, am grateful for the existence of causes like Women in Translation Month, which celebrates the excellent work produced by women around the world and also urges towards an increased conscientiousness about our reading choices. In solidarity with our fellow comrades who support global literature, below are some incredible opportunities you can take advantage of this August.

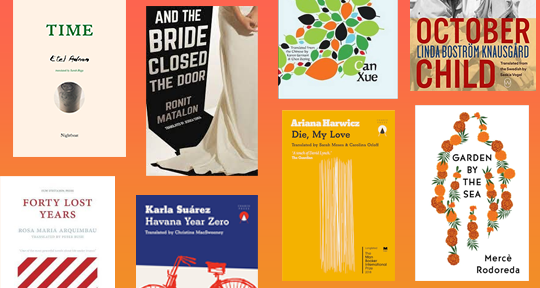

Many presses are currently offering promotions for the duration of WIT Month. One of our favourites, Open Letter Books, is offering a generous discount for the women-written and women-translated books in their lineup. Some recommendations I can make confidently include Mercè Rodoreda’s Garden by the Sea, a gorgeously lyrical fiction of 1920s Barcelona; Marguerite Duras’ The Sailor from Gibraltar, of that terrific Durassian ardor and intimate poetry; and Can Xue’s Frontier, masterfully multilayered and graceful in its surrealism. Fum D’Estampa, a press specialising in Catalan literature, is also offering discounts on all their titles, with Rosa Maria Arquimbau’s brilliant melding of the personal and the political, Forty Lost Years among them.

The wonderful Charco Press, which time and time again has brought out exceptional Latin American works, has put together special bundles of their texts—three carefully curated sets of three books each. “Revolutions” includes Karla Suárez’s Havana Year Zero, a sharp and attentive novel about unexpected connections during Cuba’s economic crisis; “Interior Journeys” features the subversive, cerebral work of Ariana Harwicz; and lastly, “Stories of Survival” gathers narratives of persistence against violence and trauma, with Selva Almada’s incredibly powerful Dead Girls among them.

World Editions is another publisher getting it right, partnering with Bookshop to provide a list of highlighted titles. Included is Linda Boström Knausgård’s October Child, a poetic and elegant autofiction about the escaping borders of reality in her experiences with mental illness and memory loss. The Last Days of Ellis Island, the award-winning novel by Gaëlle Josse that centres around the painful tenets of migration, is also up for grabs. READ MORE…