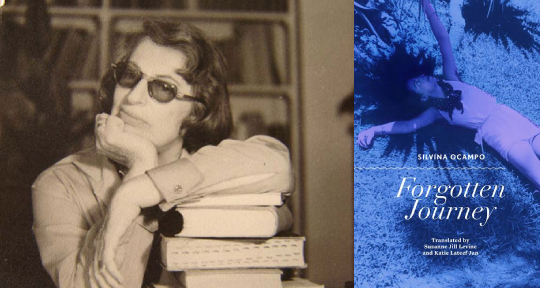

Forgotten Journey by Silvina Ocampo, translated from the Spanish by Suzanne Jill Levine and Katie Lateef-Jan, City Lights Books, 2019

Silvina Ocampo (1903-93) was once called “the best-kept secret of Argentine letters.” Luckily for Anglophone readers, however, more of her work is being gradually revealed, most recently with two publications by City Lights Books: The Promise and Forgotten Journey. The Promise is a novella which Ocampo spent twenty-five years completing, whilst Forgotten Journey, translated by Suzanne Jill Levine and Katie Lateef-Jan, is her debut piece of fiction, a collection of twenty-eight short stories originally published in 1937 as Viaje olvidado.

Ocampo may be under-recognized outside of Argentina, but during her lifetime she was part of an elite literary and intellectual circle formed by Jorge Luis Borges. Along with Borges, and her eventual husband Adolfo Bioy Casares, she collaborated on a famous anthology of Fantastic Literature and formed friendships with authors such as Virginia Woolf, Paul Valéry, Lawrence of Arabia, Federico García Lorca, and Gabriela Mistral. She was also a visual artist, having trained in Paris under Fernand Léger and the surrealist painter Giorgio de Chirico.

These surrealist influences are evident in her writing, and there is undoubtedly a fairytale quality to Ocampo’s stories: fairytale in the sense of its truest origins—innocence is flooded with the dark and the ominous, childhood confronts and battles adulthood. Throughout Ocampo’s tales, there is always a moment when death enters, knocking the innocent out. And these stories are dark: a horse is whipped to death, a servant murders the young son of her mistress, a woman’s pet is brutally killed by a jealous lover. The duality of dream and nightmare is always present, similar to writers such as Leonora Carrington, Angela Carter, and Clarice Lispector. In a 1982 interview with Noemí Ulla, Ocampo says that Lispector wanted to meet her in Buenos Aires, and Ocampo was devastated not to have done so before Lispector’s death in 1977. READ MORE…