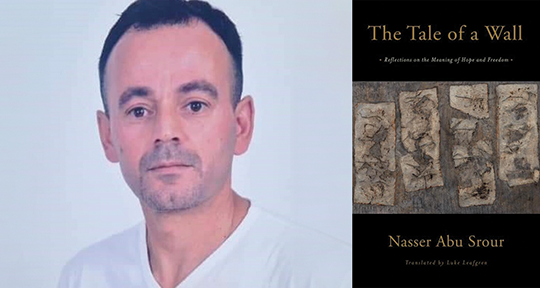

The Tale of a Wall: Reflections on the Meaning of Hope and Freedom by Nasser Abu Srour, translated from the Arabic by Luke Leafgren, Other Press, 2024

In his opening note to the readers of his prison memoir, The Tale of a Wall, Palestinian poet Nasser Abu Srour wishes a “rugged time” to those who are heading into his scintillating prose, a terrain which is also interspersed with charged moments of verse. Indicating that its author is a romantic at heart, this philosophical and nihilist work of mental abstraction was inspired by the “womb of a concrete wall” that has held Abu Srour since 1993, when he was given a life sentence at the age of twenty-three for being an alleged accomplice in the murder of a Shin Bet intelligence officer.

As literature, The Tale of a Wall is a visceral, Dionysian feast of words, lain with a delicate hand. Fired by righteous indignation and howling with a disembodied eccentricity, Palestinian self-determination is here distilled into a single voice, tortured within the echo chambers of a confession table and the paper cuts of intellectualism, finishing with a full course of epistolary melodrama. The memoir itself is cleaved in two, with the first half dedicated to letting go, to saying farewell to the world after his incarceration in Hebron Prison in the last year of the First Intifada. The latter portion is devoted to his relationship with a woman named Nanna, a diaspora Palestinian who returns to her ancestral homeland to capture his heart with a power rivalling that of Israel’s occupying force.