Skiing

Of all outdoor sports, skiing is the most dependent on “conditions”; so it is with some confusion that we come across this incredible sentence, from Arthur Waley’s short essay “Waiting for the New”:

But the truth is that for the skier time does not count.

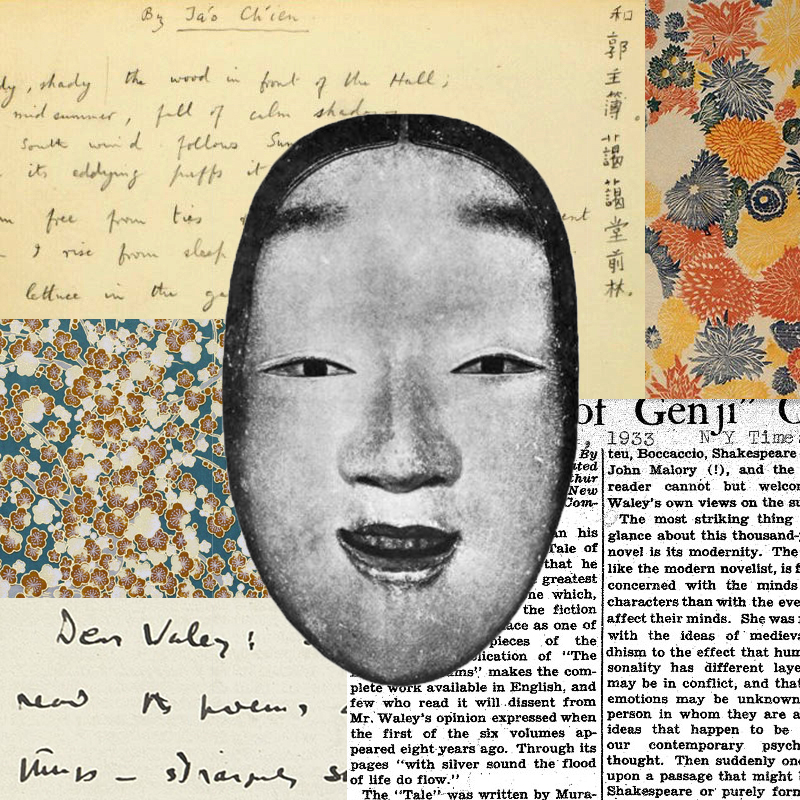

As truths go, this one sounds strange—especially coming from the man who essentially introduced ancient Chinese and Japanese literature to 20th century-English readers. But Waley knew what he was talking about. Over four decades and over two dozen books (an output rivaled only by his fellow Fabian, Constance Garnett), he developed an exquisite ear for the way that time changed words. At the same time, as a poet, he understood that the gulfs separating two seemingly distant eras could be bridged, unexpectedly, by a single act. Later in the same article, he described the skier’s patience:

Waiting is waiting, whether it be for a night or for six months; and inversely the prospect of a ski-run is as exciting, day after day, to the rentier or pensioner who spends Michaelmas to May Day on the snow, as to the breadwinner who snatches a fortnight at Christmas. Each, on waking, thrills at the thought ‘today I am going to ski’; each has sat for hours in heavy and perhaps wet skiing boots, merely to put off the moment when he must confess to himself ‘today the skiing is over.’

The skier in Waley’s description no more ignores the weather than the translator would ignore the echoes of an archaic verb tense; on the contrary, he steeps himself in the conditions of his art, sure that if he waits long enough, his moment will come. The clouds will part and time collapse like a Mad Fold-In, creating a moment that is simultaneously a repetition of previous moments and unique. The name that Waley’s article gives to this miracle will be familiar to readers of either ancient Chinese literature or 20th century poetry. It is “The New.”

Biography

In a note to his 1934 translation and study of the Tao Te Ching, Waley explains the concept of fan-yen:

The ‘which of you can assume murkiness…to be clear’ is a fan-yen, a paradox, reversal of common speech. Thus ‘the more you clean it, the dirtier it becomes’ is a common saying, applied to the way in which slander ‘sticks’. But the Taoist must apply the paradoxical rule: ‘The more you dirty it, the cleaner it becomes.’

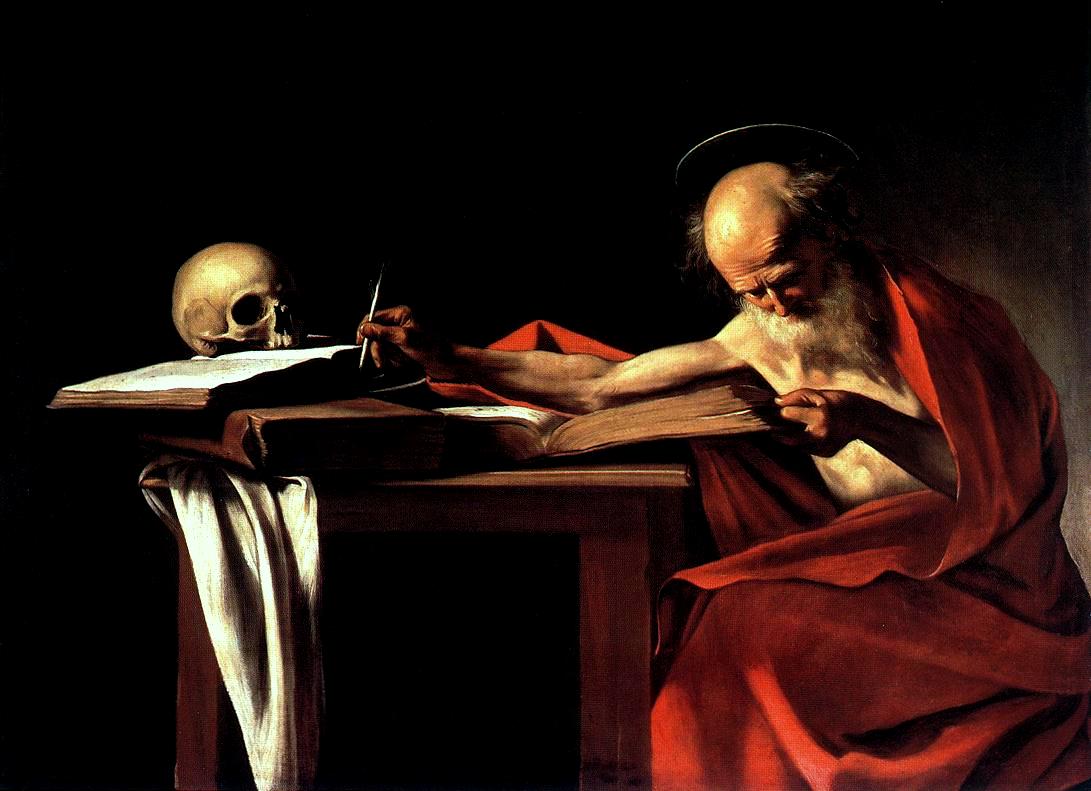

As a tool for thought, paradox has a long history in Western and Eastern literatures, but its use in biography has been limited. The mythmaking urge is too great, which means that most of the time biographers from Samuel Johnson to David Remnick have found themselves “cleaning” their subjects’ lives in a way that may sound and even be true, but which hides a certain messiness. The life in question becomes a story with a plot and theme—which is all well and good until you think about your own life, and the thousand things that any story about it would have to leave out in order to make any sense.

The life of Arthur Waley breaks the biographer’s storytelling urge in a number of ways, not the least of which is the fact that Waley didn’t write much about himself. He kept no diary and destroyed his letters, leaving a space, or network of spaces, where most of his contemporaries left maps. Perhaps most importantly, his insane productivity occurred almost exclusively in translation—a discipline that traditionally prides itself on self-erasure. Because of this, any attempt to make a story out of him has to confront the fact that there is, ostensibly at least, not much “him” to make a story out of. READ MORE…