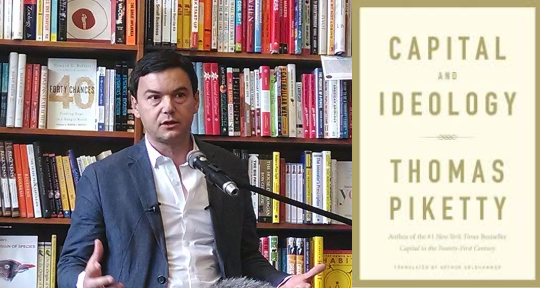

Capital and Ideology by Thomas Piketty, translated from the French by Arthur Goldhammer, The Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2020

It’s rare for an economics book to make much inroad into non-academic circles, but the French economist Thomas Piketty did just that with his surprise success Capital in the Twenty-First Century, published in 2014 with an English translation by Arthur Goldhammer. This impressive work warns of the corrosive impacts of economic inequality, which has spiraled out of control in the last few decades. Piketty’s thesis—and perhaps the greatest success of the study—boils down to a simple equation: r > g, where r represents the rate of return on capital and g represents the rate of economic growth. Piketty warns of a future where returns on wealth will outpace all new forms of economic growth, entrenching all existing fortunes ever deeper, and only further those with more meagre supplies of capital. Piketty’s warnings seem to have struck a chord, although not without criticism. The global and historic scope of this study left many corners of the world understudied and with little room to understand the roots of inequality before the nineteenth century.

Piketty’s newest book, Capital and Ideology, again translated by Arthur Goldhammer, serves as a logical continuation of the project undertaken in his earlier research. If anything, it takes an even more ambitious approach to the seemingly intractable problem of economic inequality, offering both a diagnosis and potential treatments of our global malaise. Despite Piketty’s disciplinary background in economics, Capital and Ideology emphasizes the central importance of political and ideological change rather than changes in monetary policy or trade agreements. At his best, Piketty draws the potential dry discussion of economic systems into the complex interplay of human systems of politics, ideology, and history, and into the manifold ways these systems have taken shape throughout time and place. Perhaps most invigorating of all is the degree of faith Piketty places in human imagination and the ability to right wrongs and make active decisions to shape our collective future.

As he reminds us throughout Capital and Ideology, the accumulated wealth and power of the European elites in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries may have seemed intractable, and the political deference to the propertied classes total, but the century played out differently than many could have predicted at its onset. If the twenty-first century is to take such a path, global political and economic reforms will be necessary, and the range of ideological possibilities needs to be widened from those of the previous century. The crisis of the world wars and Great Depression coupled with new political mobilizations to rein in the influence of wealthy elites brought inequality to its lowest point ever. As Piketty likes to remind us, even Sweden, often bandied about as the paramount example of egalitarianism did not begin the twentieth century as such. In fact, he shows quite the opposite, where the amount of political representation in Sweden was proportionate to wealth. Nevertheless, the relative successes of social democracy were able to transform Swedish society in only a few generations. On the other hand, the relative equality of the postwar era has rapidly given way over the last few decades, showing no sign of slowing down. READ MORE…