This edition of Principle of Decision—our column that highlights the decision-making processes of translators by asking several contributors to offer their own versions of the same passage—provides a look at how translators render the subtleties of a poem with multiple layers of meaning in a new language.

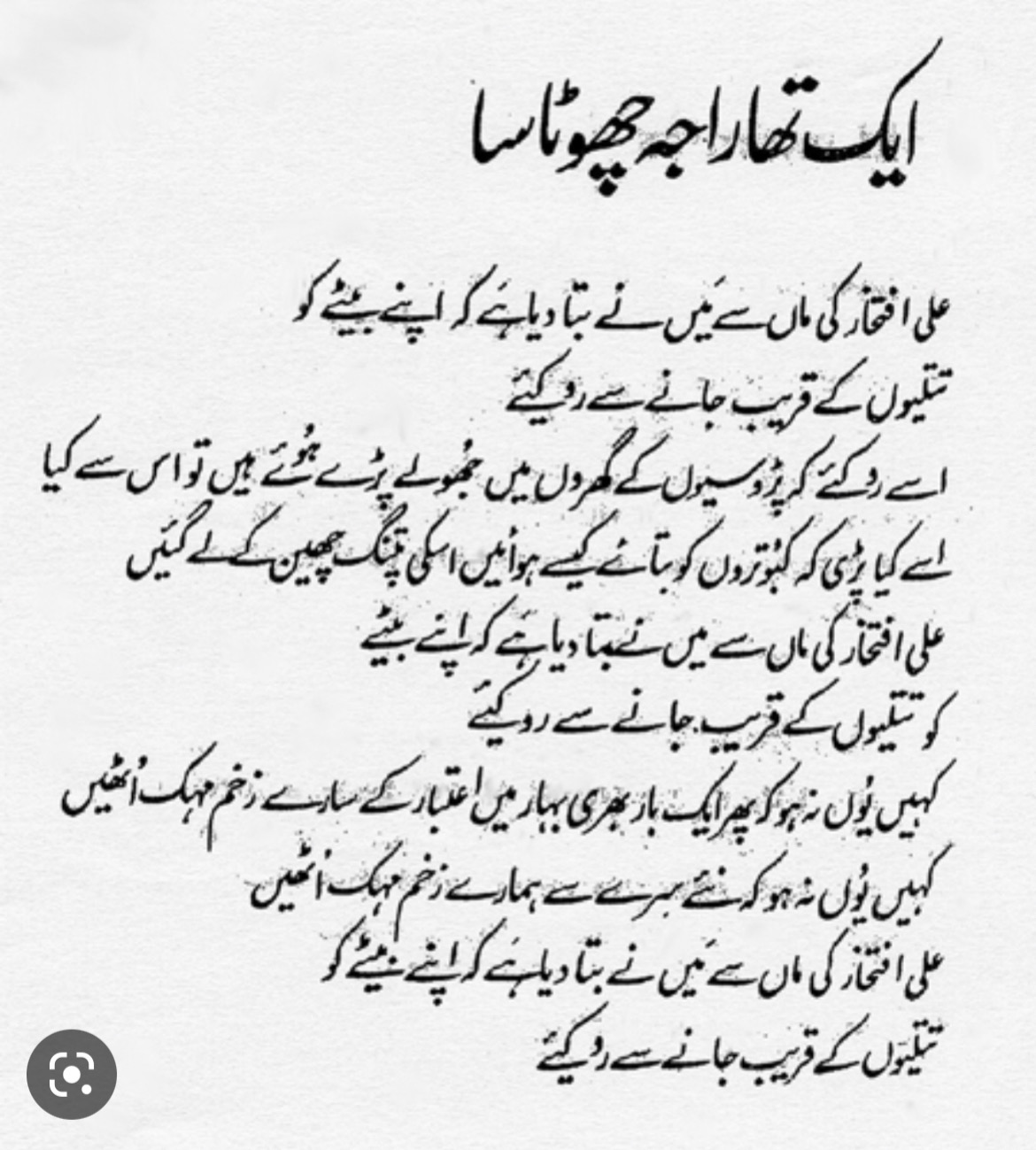

I chose a poem by Iftikhar Arif, a revered Urdu poet. It was written for his son, Ali, and was published in his first volume of poetry, Mehr-e-Doneem (The Divided Sun, Daniyal Publications, 1983). This poem is a father’s sendoff; as he says a farewell to his son, he feels a lump in his throat and slips some blessings and lessons for the future into his farewell, barely masking his fear. A companion piece, the short poem “Dua” (Prayer), was written for his daughter, and published in the same volume, containing a similar wish of goodwill.

The poem is not to be read at face value. Defeat is baked into its premise, and what the poet is saying out loud, he knows to be the opposite of the truth. It is a prayer for the impossible, asking a grown man not to lose his innocence. There is rupture in the title itself: Aik tha raja chota sa—(once upon a time) there was a little prince. It’s the tone in which you speak to a child, who is uninitiated into the realities of life. It’s the tone of lullabies. There is a clinging to a make-believe world in the language, an attempt to soften the edges, to make the truth less harsh, to almost wish it away.

The first word of the first line starts with the son’s full name, Ali Iftikhar. The once-little prince is a grown man, which the poet acknowledges, but then slips back to addressing the grown man through his mother, a line repeated thrice in the poem: “I have told Ali Iftikhar’s mother not to let him…”.

Throughout the short poem, there is a push and pull. On one hand, there’s an attempt to glaze over the truth and to control the circumstances; on the other hand, there’s truth leaking through the veneer of denial. The repetition is like a broken record to convince the speaker himself. There is also a contrast between the naïveté of the language and the knowledge of truth beneath it—and bridging both, a father’s love. He tells the son to stay away from the corruption of the world by asking his mother to keep him from transgressing the different circles of protection: the garden, the neighbour’s garden, the street and the world beyond. Which grown man hasn’t transgressed these limits?

The four translators, sensitive to the central challenge posed by the poem, have found different solutions to address the tug in the original. Farah Ali is alert to the rhythm and pace in the original. Hammad Rind pays attention to calibrating the register and forms of address, important tonal considerations for the poem. Haider Shahbaz brings an experimental take to his reading, leaning into its dark undertones. Sabyn Javeri sees the poem through a feminist lens, asking questions that trouble her as a woman.

I’ve always seen translation as a conversation—a conversation between the author and the translator, the translator and the work, a translator and other translators, a translator and a reader. This folio shows how rich that conversation can be. Each of the four translators interacts with the same, short poem through the filter of their individual personalities.

—Naima Rashid READ MORE…