In this month’s roundup of translations, we review the works of two iconic feminist writers, Forough Farrokhzad and Kyung-sook Shin, who trace, narrativize, and engage with gender and politics in its most vivid and various forms. In dialogue with the greater schemes of sexuality, passions, and poetics, these women writers work within and trespass the boundaries of their language to paint bold new portraits of the world, as a place lived in the mind.

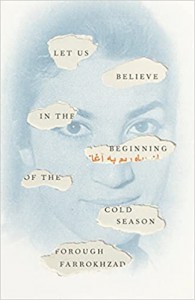

Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season by Forough Farrokhzad, translated from the Persian by Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr., New Directions, 2022

Review by Georgina Fooks, Director of Outreach

A poet of (com)passion: such is just one of the myriad ways to encapsulate the unique encounter with Forough Farrokhzad and her poetry. One of 20th-century Iran’s most celebrated and outspoken poets, she was controversial for the ways in which she lived and loved—openly, in transgression of patriarchal societal norms—and as a result, her work was banned for more than a decade after the Islamic Revolution. Yet, her legacy has lived on in illicit fragments and poems shared between readers, and now she is one of Iran’s best-loved women poets, widely read and translated. Through the work of Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr., this latest translation seeks to offer lovers of poetry a comprehensive critical edition of Farrokhzad’s work.

Born in 1934, the poet’s turbulent life was tragically cut short by a car accident in February 1967, leaving us with a nonetheless prolific oeuvre spanning a wide range of creative endeavours. A poet, filmmaker, actress, painter, and more, her work across various formats bears witness to the vibrancy of human life in the face of suffering, and to the wonders and pleasures of living despite overwhelming pressures and pushbacks.

Farrokhzad is undoubtedly a poet of romance. Drawing on a long tradition of Persian love poetry (Rumi was one of her great inspirations, according to Sholeh Wolpé), Farrokhzad’s work remains unique in its fervent declarations of physical and emotional intimacy, opening up possibilities for women poets in the Persian language. The opening poem of the collection, ‘Captive’, points to the vastness of desire:

I want you, and I know that never

will I hold you as my heart desires

You are that clear bright sky

I am a captive bird in the corner of this cage