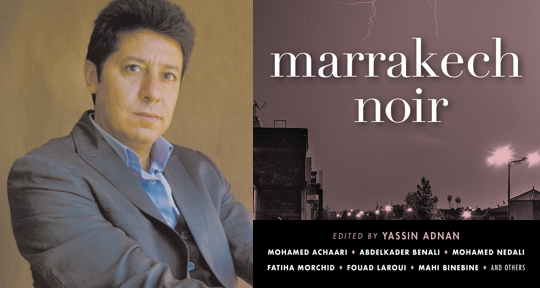

This Translation Tuesday, Mehdi Charef recounts his father’s teenage experiences in a newly-built Parisian banlieue. Social housing holds undreamed of comforts for his migrant family, and apprehension quickly turns to delight. Comfort! Safety! Privacy! Hot water! A new, fuller life beckons in the projects, and it involves quantities of rock ‘n’ roll, girlfriends and Carson McCullers.

It’s the Chinese building manager who told us that we had to move. The immigrant families who had lived in shacks—think shipping containers turned ruins with wear and tear over the past eight years—in the cité de transit, or transitional social housing, on Rue de Valenciennes in Nanterre would now need to pack their bags. Two feelings arise with the announcement of the news: anxiety and melancholy. This move represents a separation. We know where we came from but not where they are taking us. They didn’t ask us about anything, and they aren’t telling us about anything. We are leaving our most recent safe place.

In the bidonville, I had learned that there were Algerians outside of the ones in the village where I was born. In the cité de transit, I had learned Berber and African expressions as well as all the Portuguese curse words.

It isn’t the shacks that I liked but the people who lived in them. In front of them, I kept my head held high because I was like them. It’s only in front of my French classmates that I was ashamed…

Our housing project is going to be demolished. The construction of a large industrial park is set to take its place: la Défense.

Our new apartment is in Cité Rouge. The neighborhood is named that because of the brick façades of the buildings. It’s in the city Gennevilliers surrounded by small, old houses. We are no longer the isolated immigrant population. People walk down our alleys, underneath our windows. We are no longer the shame of those who were kind to us. We became visible before we were heard… READ MORE…