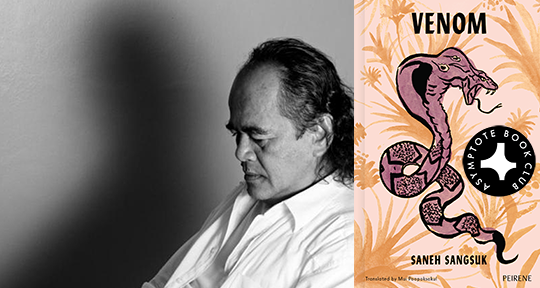

A story about the dissolving borders between human and animal, life and death, love and cruelty, Venom by Saneh Sangsuk is a kind of philosophical fairy tale, with both danger and beauty always lurking at its edges. Told through shifting perspectives in poetic prose, this slim novel is densly packed with ideas and energy, providing a thrilling introduction to Sangsuk’s work for English-language readers.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Venom by Saneh Sangsuk, translated from the Thai by Mui Poopoksakul, Peirene Press, 2023

The world is full of poetry; the world is full of cruelty—this is not a contradiction. As I read Saneh Sangsuk’s deceptively slim novel Venom, I was reminded of Laura Gilpin’s “Two-Headed Calf.” At barely nine lines, Gilpin’s poem also has depth that reaches far beyond its brevity. The first stanza begins with a warning (that the idyllic pastoral will soon be disrupted), while the final stanza establishes a heart-wrenching and melancholic portrait of a recently-born, two-headed calf revelling in the light of the moon, “the wind on the grass,” and the warmth of its mother. The beauty of Gilpin’s poem lies in the way it holds two worlds in its lines, but also in how it makes possible for a cruel tomorrow to never arrive. In a sense, by returning to this poem, we are returning to a moment in another world where a two-headed calf—this “freak of nature”—is frozen in an eternal evening of joy and love.

I found in Venom the same sensations, the same negotiation between poetic beauty and cruelty. The former comes quickly and easily, as the book opens with a little boy contemplating a mesmerizing sunset in the Thai countryside: “Over the horizon to the west, the clouds of summer, met from behind by sunlight, glowed strange and lustrous and beautiful.” Additionally, the first thing we learn about this boy is that he was granted the privilege of naming his family’s eight oxen, and he had been eager to fulfil this task with care and artistic flare. He calls the animals by names like “Field, Bank, Jungle and Mountain—Toong, Tah, Pah and Khao,” and “Ngeun and Tong, Silver and Gold,” or “Pet, Ploy, Ngeun and Tong.” These group of names speak to him with prosodic logic: some rhyme, and others provide a chance for alliteration. All in all, they belong to a group of words that “sounded like [they] could be poetry,” a phrase that Sangsuk repeats twice. This act of naming, the author suggests, is an act of writerly creation. While the world is not inherently poetic, some people are more prone to make poetry from its elements. READ MORE…

A Pointed Atemporality: Mui Poopoksakul on Translating Saneh Sangsuk’s Venom

He's very aware of the rhythm and musicality of this text . . . he said it should take something like an hour and thirty-seven minutes to read.

In our May Book Club selection, a young boy struggles with a snake in the fictional village of Praeknamdang, in a tense battle between beauty and cruelty. In poetic language that is nostalgic for the world it describes without romanticizing it, Saneh Sangsuk creates a complex and captivating world. In this fable-like story there are no simple morals, in keeping with Sangsuk’s resistance to efforts to depict a sanitized view of Thailand and to the idea that the purpose of literature is to create a path to social change. In this interview with translator Mui Poopoksakul, we discuss the role of nature in the text, translating meticulous prose, and the politics of literary criticism.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Barbara Halla (BH): How did you get into translation, especially given your law background?

Mui Poopoksakul (MP): I actually studied comparative literature as an undergrad, and then in my early twenties, like a lot of people who study the humanities, I felt a little bit like, “Oh, I need to get a ‘real job.’” I went to law school, and I worked at a law firm for about five years, and I liked that job just fine, but it just wasn’t what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

So, I started thinking, What should I be doing? What do I want to do with myself? I had always wanted to do something in the literary field but didn’t quite have the courage, and I realized that not a lot of Thai literature been translated. I thought, If I can just get one book out, that would be really amazing. So, I went back to grad school. I did an MA in Cultural Translation at the American University of Paris, and The Sad Part Was was my thesis from that program. Because I had done it as my thesis, I felt like I was translating it for something. I wasn’t just producing a sample that might go nowhere.

The whole field was all new to me, so I didn’t know how anything worked. I didn’t even know how many pages a translation sample should be. But then I ended up not having to worry about that because I did the book as my thesis.

BH: You mentioned even just one book, but did you have any authors in mind? Was Saneh Sangsuk one of those authors in your ideal roster?

MP: I wouldn’t say I had a roster, but I did have one author in mind and that was Prabda Yoon, and that really helped me get started, because I wasn’t getting into the field thinking, “I want to translate.” My thought was, “I want to translate this book.” I think that helped me a lot, having a more concrete goal.

READ MORE…

Contributor:- Barbara Halla

; Languages: - English

, - Thai

; Place: - Thailand

; Writers: - Mui Poopoksakul

, - Prabda Yoon

, - Saneh Sangsuk

; Tags: - Deep Vellum

, - environmentalism

, - literary criticism

, - nature

, - nature in storytelling

, - pacing

, - pacing in translation

, - Peirene

, - respect for nature

, - rhythm

, - rhythm in translation

, - social commentary

, - storytelling

, - Thai literature