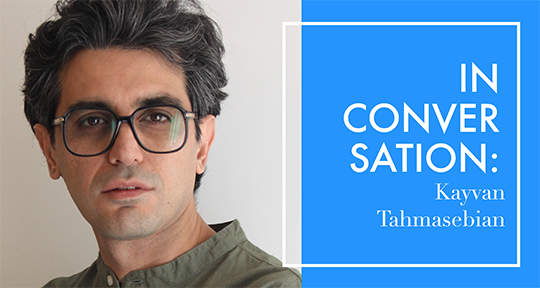

Born and raised in the city of Isfahan in central Iran, Dr. Kayvan Tahmasebian is a writer and scholar whose work examines Persian literature’s place in the constellations of what is labeled as ‘world literatures’, and a poet and translator working on Persian, English, and French. Dr. Tahmasebian’s co-translation of House Arrest (with Rebecca Ruth Gould, Arc Publications, 2022) by Iranian poet Hasan Alizadeh was recently shortlisted for the Sarah Maguire Prize for Poetry in Translation, and he has translated and studied Persian-language texts from ancient Persian astrology and dream writing to contemporary Iranian modernist poetry.

In this interview, I spoke with Dr. Tahmasebian on his translations from the Persianate literary world, both modern and from antiquity, as well as the potential expansion of activism through translation.

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (AMMD): First of all, congratulations on being shortlisted for the 2024 Sarah Maguire Prize for Poetry in Translation for co-translating Hasan Alizadeh’s avant-garde House Arrest (Arc Publications, 2022). You also worked with Rebecca Ruth Gould on your translation of High Tide of the Eyes (2019) by Bijan Elahi, one of the figureheads of Iranian modernist literature. Could you tell us the experience of translating both Alizadeh and Elahi?

Kayvan Tahmasebian (KT): Bijan Elahi is a highly experimental poet and translator in modern Persian poetry. He moves through different language registers—formal, colloquial, archaic, even obsolete ones. He’s also a difficult poet. His poetry is intricate and can be quite challenging in its images and structures. For me, translating Elahi was an exercise in trying to grasp his poetic fluidity. And by ‘grasp,’ I mean something similar to what a photographer does when capturing a fleeting moment—seizing something that’s just passing by. The tough part was that his language is so volatile, and the perspectives he offers on his subjects can be so intuitive, that they sometimes clash with English poetry, which tends to be more discursive and analytical.

Hasan Alizadeh is almost the opposite of Elahi in many ways. It is the simple, the everyday, that speaks through his poetry. But that simplicity is deceptive. It’s a mask that hides the real delicacy of his poems. What I really admire about Alizadeh is how he uncovers the subtleties of spoken Persian, the little hidden dramas that play out in the unnoticed corners of everyday conversations. Translating his poems was about getting in touch with that extraordinary intimacy in his language. I actually had the chance to meet Mr. Alizadeh in Tehran in 2023, and it was fascinating. The way he recited his own poems, the way he seemed almost surprised by the stories his poems tell—about chance encounters, moments of forgetfulness, or the magical appeal of everyday objects—was fantastic. READ MORE…