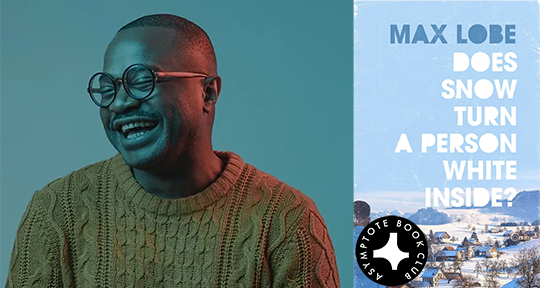

In our December Book Club selection, Does Snow Turn a Person White Inside?, Swiss writer Max Lobe paints a vivid psychic landscape of migration, queerness, and class. Centred around an incredibly intimate mother-son relationship that crosses from Cameroon to Switzerland, Lobe addresses the politics of a contemporary, itinerant existence with humour, wisdom, and frankness. In this following interview, Laurel Taylor speaks to Lobe and translator Ros Schwartz about the concept of a “national literature,” textual musicality, and what it means to belong somewhere, nowhere—or everywhere.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Laurel Taylor (LT): Does Snow Turn a Person White Inside? is a novel with an immigrant at its center, and the book has been described as a contemporary story of alienation, that feeling of belonging nowhere catalysed by migrancy. Max and Ros, how do you think the concept of belonging fits in this book? Where does the nature of belonging fit overall in books that speak of migration?

Max Lobe (ML): The fact of belonging nowhere is something that really speaks to me. I was born in Douala, [Cameroon,] and then I moved from Douala to Lugano, which is in the Italian part of Switzerland. Today, I live in Geneva, and most of the time I’m always travelling, travelling, travelling, to preach the gospel of literature, of my literature, of my voice.

In Cameroon, back in the day, I couldn’t feel at home because I didn’t fulfill the criteria of being a man. I was very girlish. And you see me with the red lipstick now because I’ve come to terms with who I am. Then, when I moved to Switzerland, there was another problem, because I discovered that I was black in our classroom at Università della Svizzera italiana, the Lugano university.

In those three years, I thought to myself: “Where is my place?” I think that we, or I, can make anywhere our own place, but you need to want it. You need a willingness if you want to belong to a place—with courage, with humour, with lots of passion. Today, I think, “Everywhere I go can be my place.” That is what I wanted to communicate in this book.

Ros Schwartz (RS): I think this idea of belonging both in this book and in other books written by migrants, is that being granted citizenship does not automatically create a sense of belonging. Mwana, the narrator, is constantly reminded that he’s an outsider—through the Black Sheep anti-immigrant campaign. At first, he doesn’t even realize it’s directed against him, and then his lover—Ruedi—goes with his family to the famous Grütli Meadow, which the book describes as: “the very one where the Swiss Oath had been signed at the end of the thirteenth century, while we Bantus were still walking barefoot in the forest among the animals.” So, there is this continual reminder of being other.

I think in books that speak of migration, it’s a thread that runs through generations. The children of migrants are continually looking at both countries through a lens of otherness; they don’t feel completely at home in their parents’ country of origin, or they don’t feel completely at home in the adoptive country. People are expected to come down on one side or the other.