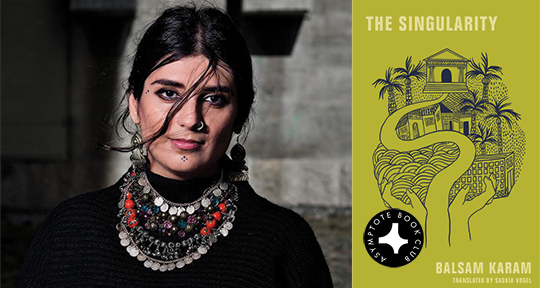

In The Singularity, Swedish author Balsam Karam instills a startling and deeply profound gravity within the devastating fractures of life—mothers who lose children, migrants who lose countries, and the emotional maelstroms stirring at the precipice of disappearance. With an extraordinary style that exemplifies how poetics can search and unveil the most secret aspects of grief and longing, Karam’s fluid, genre-blurring prose is at once dreamlike and harrowingly vivid, with the remarkable sensitivity of translator Saskia Vogel carrying this richness through to the English translation. We were proud to select this novel as our January Book Club selection, and in this following interview, Vogel speaks to us about how Karam’s writing works to destabilize and shift majority presumptions, as well as how literature can echo, verify, and perhaps change the way we live.

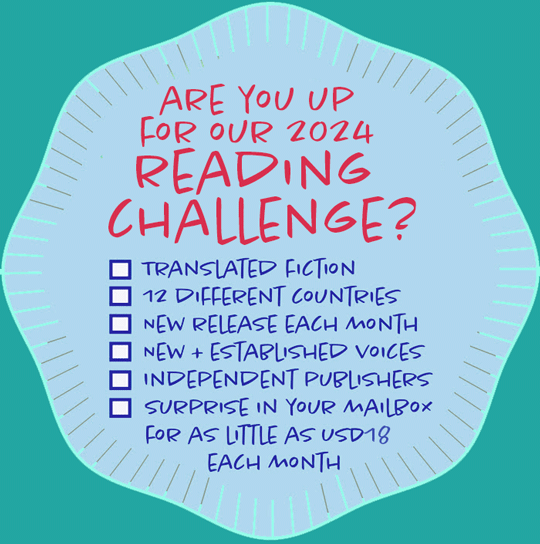

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Rachel Stanyon (RS): How did you come to Balsam Karam’s work?

Saskia Vogel (SV): I first encountered Balsam’s work through Sara Abdollahi, one of my favorite literary critics in Sweden—she’s full of integrity, and really cares about literature and its transformative potential. She had done a podcast with Balsam, and their conversation really struck me, especially Balsam’s extraordinary representation of solidarity. This is exemplified in her first novel, Event Horizon, which, as I understand, is connected to The Singularity like a kind of diptych; they’re of the same world, and written with the same sorts of strategies—for example, a lot of the details of place, location, and identity are unstated. I find this aesthetic really compelling.

Balsam assumes that she’s writing into Sweden and a majority white culture, and she doesn’t want to give people an easy out where they can say, “I’ve been to Beirut. It’s not exactly like that.” She instead strips away detail and, in The Singularity, focuses on loss and the effects of war on individuals, as well as on migration and racism.

Another extraordinary feature of her prose is that the white gaze is decentered, which works to shift how the presumed audience reads and perceives some of the most pressing and potent human experiences of our time. She moves us away from the particularities of politics, and tries to make us understand what it feels like to be in a certain position. In that way, she really encourages and facilitates a deep growth and compassion—if you’re open to it, I guess. READ MORE…