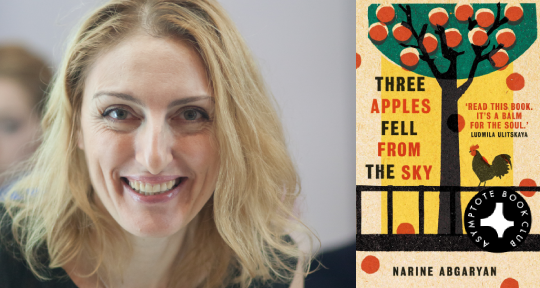

On the tails of its celebrated success in Russia, Narine Abgaryan’s award-winning novel, Three Apples Fell From the Sky, is now available to English-language readers in Lisa C. Hayden’s expert translation. This tripartite tale takes on the form and mysticism of fable to spin a narrative of a village constantly at the mercy of catastrophe, and, as Josefina Massot points out in this following review, may act as a poignant response to our current age of precarity. With its characteristically sensitive descriptions, Abgaryan’s work explores the human things that evolve in the aftermath of disaster; in times that teeter on the edge of dystopia, it invites us to read our lives into them—a reminder that one of literature’s most enduring gifts is its expansiveness.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

Three Apples From the Sky by Narine Abgaryan, translated from the Russian by Lisa C. Hayden, Oneworld Publications, 2020

They say the best way to ward off anxiety is to focus on the here and now. At the moment, though, “here” is a seemingly shrinking apartment and “now” is any time I hit refresh on decidedly growing pandemic statistics. It’s been that way for weeks, so when Abgaryan’s novel hit my inbox (my locked down city’s impermeable to foreign paperbacks), I was desperate for a folktale. What better than a nowhere, no-when land to flee the grim here-and-now—a tale that would end happily, or at the very least end, flouting the boundless infection curves that plagued my feeds and fed my dread?

Three Apples Fell From the Sky isn’t the strictly uchronic utopia I’d expected: most of it unfolds in the Armenian village of Maran during the twentieth century. When I googled “Maran Armenia,” however, I found no such place, and the search I then ran on “Մառան Հայաստան,” courtesy of Google Translate, yielded a stub on a village for which “no population data had been retained.” In fact, there seems to be no data at all—just an unverified note on villagers’ deaths and deportations during the Genocide. As far as I was concerned, Maran might as well have been fictional. Grounding the novel in time proved equally tricky: save for a few scattered references to telegrams or left-wing revolutions, its protagonists could’ve just as easily lived through the 2015 constitutional referendum or the Russo-Persian Wars. My sense of chronology was further challenged by recurring flashbacks, occasional changes in verb tense, and the Maranians’ own cluelessness regarding dates. Near perfect fodder for escapism, you’d think, but by the time I’d put it down, I was more firmly rooted in the times than ever. READ MORE…