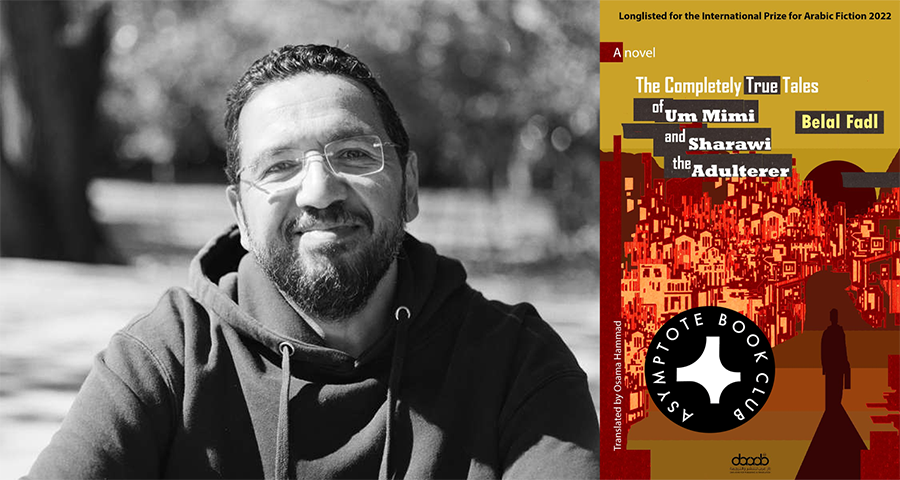

Upon the premiere of Youssef Chahine’s Cairo at Cannes, the Egyptian critics in attendance resented its unflinching portrayal of the city’s poverty and density, claiming it as a derogatory and inciting the film’s eventual ban. In The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi and Sharawi the Adulterer, author and screenwriter Belal Fadl takes a similarly undaunted look at the capital: its swarming underbelly, its suffocating divides, and its unrelenting pressures that bloom both tragedy and absurdity. Written in a captivating style that listens carefully to the city’s manifold ranges, Fadl is determined to pull back the curtains, putting a middle finger up to politeness or grandeur, and drawing instead on chaos, comedy, and linguistic richness to portrait a Cairo full of adrenaline, be it from laughter, thrill, or the sheer will to survive.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi and Sharawi the Adulterer by Belal Fadl, translated from the Arabic by Osama Hammad, DarArab, 2025

Belal Fadl’s The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi and Sharawi the Adulterer announces itself with a provocation and never retreats from it: “Whenever I tell my story, I say that what led me to live with Um Mimi were two Polish breasts with unparalleled nipples.” From this opening confession, the novel signals that nothing sacred will be protected from language, and nothing obscene will be softened for the reader’s comfort. But this is not bravado for its own sake—Fadl’s novel is built on a wager: that obscenity, vulgarity, and excess are not moral failures of language, but its most truthful registers when class humiliation, bodily precarity, and institutional contempt are the subject. To read The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi (or to be more accurate, to read it in translation) is therefore to confront an ethical question: how does a translator render a voice whose truth depends on its refusal to be clean?

The novel’s narrative arc is deceptively simple (almost cliché). It’s 1991, and a young man from Alexandria arrives in Cairo to study media at Cairo University, determined to escape an abusive father and a suffocating household. His grades win him admission, but his finances dictate his fate. Having endured a humiliating stay in a flat with “decent, pious, and religious young men who knew God and had learned the Quran by heart,” he is evicted for attending an R-rated film, and ends up renting a room in the ground-floor flat of Um Mimi, a retired madam, on a nameless lane known only as “the street behind Casino Isis.” READ MORE…