These days, many of the images we see from Palestine are ones of unbearable violence—a necessary example of what Roland Barthes called “the experiential order of proof”. However, despite the vital role of these photographs in bearing witness and documenting the ongoing atrocity, there is an equally essential need to elaborate this unidimensional representation with the social soul and experienced terrain of these historically rich territories, and to thus unite the psychically separate fields of the unthinkable and the daily.

As such, it is with great urgency that writers and scholars Margaret Olin and David Shulman have collaborated to produce The Bitter Landscapes of Palestine, a compilation of photographs and texts, to be published as part of the Critical Photography series by Intellect. In their brief introduction, they state only: “We will speak of what we have seen and heard directly and what we have experienced in our bodies.” From that dedication to perception, they illuminate the extent to which intersections of photojournalism and intimate speech can establish compassionate, mutual relationships between viewers and subjects, and how photographs and poetics can be used in ways that do not seek to control information, as in the mechanisms of tyranny, but that reassert their expressive, transformative function: impressing a fragment to open up interrogations into the whole; inducing the epiphany of recognition; and offering the potential of a unified political space.

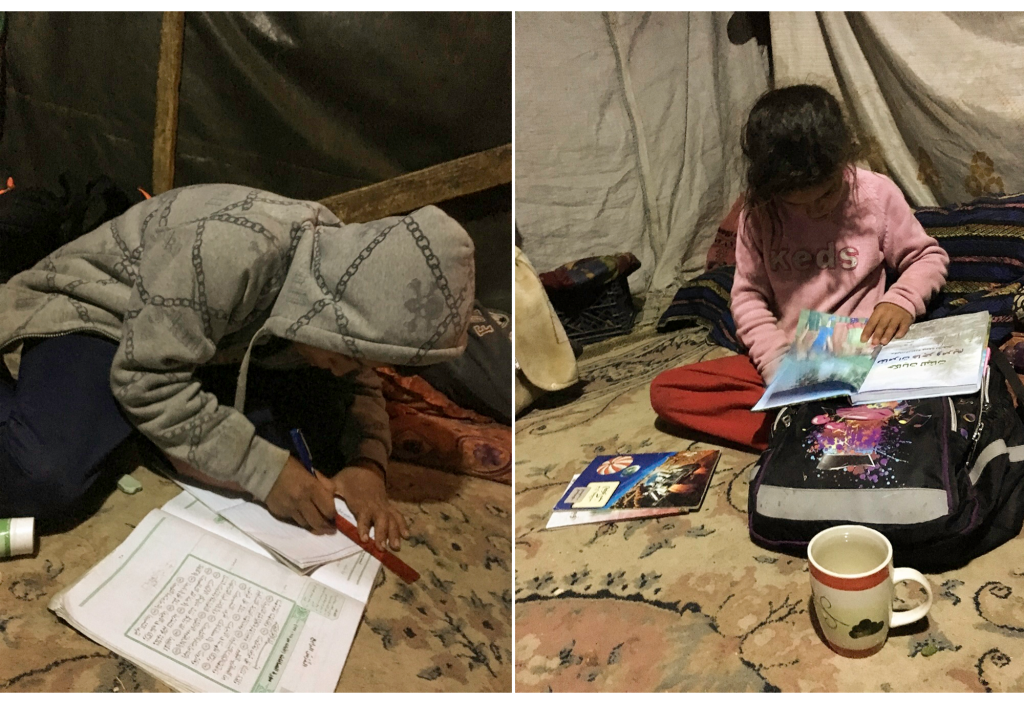

In the following excerpt, which consists of the book’s fifth chapter, titled “Arabic”, Olin and Shulman describe the sonic and interpersonal fabric of language under occupation, pairing the text with an array of images that portray communication’s various appearances: books, letters, conversations. The resulting interplay is evidence of how a single word—injustice—can grow and grow until it contains an entire country; how there is no scale for such grief, just as there is no true physicality for words, but still it is felt and carried, every day.

Susiya, March 2016

First, the music. It changes from place to place. The city Arabic of Jerusalem and Ramallah becomes gruffer, rougher, in the desert, where the guttural “q”—often pronounced only as a glottal stop, that is, a quick catching of the breath in the throat—turns into a “g.” The shepherds’ language flows seamlessly into the cries and whistles and grunts they use to speak to the sheep. At the same time, they sprinkle their sentences with the astonishing formulas of courtesy that come so naturally to the tongue: May Allah heal you, give you peace, bless your hands. We thank you, you have honored us. Welcome, you are our guests. Go in peace. READ MORE…