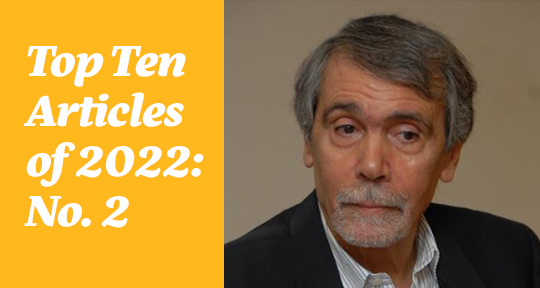

Our second most-read piece of the year is Abdelfattah Kilito’s Borges and the Blind, expertly translated from the Arabic by Ghazouane Arslane (who was also interviewed about this article on the blog by Senior Assistant Editor Alex Tan). A lithe and subtle essay on Borges’ famous short story Averroës’ Search, it glides with a rather un-essayistic lightness that belies how profuse it is with ideas. We’ll limit ourselves to pulling on one of its threads: Borges writes at the threshold between European and Arabic literatures; he is a bridger, and—why not, though Kilito never says so explicitly—a translator of sorts bringing the literature of Arabic to the West. The essay never prescribes and Kilito consciously forswears snobbery; nevertheless, as he unpacks allusions only Arabists could know and Europeans would not deign to scrutinise we find suggestions on how to read Borges’ work—and indeed any work at all rooted in an unfamiliar culture. Dismiss those foreign words and names at your peril. With Borges as with the best translations, a trove of knowledge is resting literally under your nose, if only you think to look for it. It’s a thrilling notion, and there are other ideas that spark similar thoughts throughout Borges and the Blind. Like so many articles in this year’s top ten, it very much bears rereading.

Here’s an excerpt:

One is curious, in this context, about Borges’s relationship with languages, and namely with the Arabic language. He knew, of course, Spanish and English (his grandmother was English) and was proficient in French and German. He lived in four languages, but what about Arabic? In one of his poems, a rare and equivocal verse attracted my attention: “What language / am I doomed to die in?!” This could mean in what language will death strike me, or in what language am I to die, what is the language in which it is my duty to die? Borges partly made up his mind when, wondering, he added: “The Spanish my ancestors used / to call for the charge, or to play truco / The English of the Bible / my grandmother read from / at the edges of the desert?” He mentioned the two languages closest to his heart. What is rather strange, however, is that he would die in neither of them, let alone in French or German. He would die in a fifth language he had not expected or intuited to die in, a new language he was indeed able to acquire. Which language? The Arabic language, which he had started to learn during the last year of his life. Borges learned Arabic and died or, and perhaps more precisely, he learned Arabic and thus died.

If this piece has sparked an interest in Abdelfattah Kilito’s literary criticism, your next stop has to be his Dream of a Baghdad Night, translated from the French by former team member Hodna Bentali Gharsallah Nuernberg for our Spring 2019 issue. If all this talk of bridge-building inspires you to join us behind the scenes, on the other hand, take note that we’re already advertising our first recruitment call of 2023. From Editor-at-Large to Assistant Blog Editor, check out the newly available positions here and send in your application today!