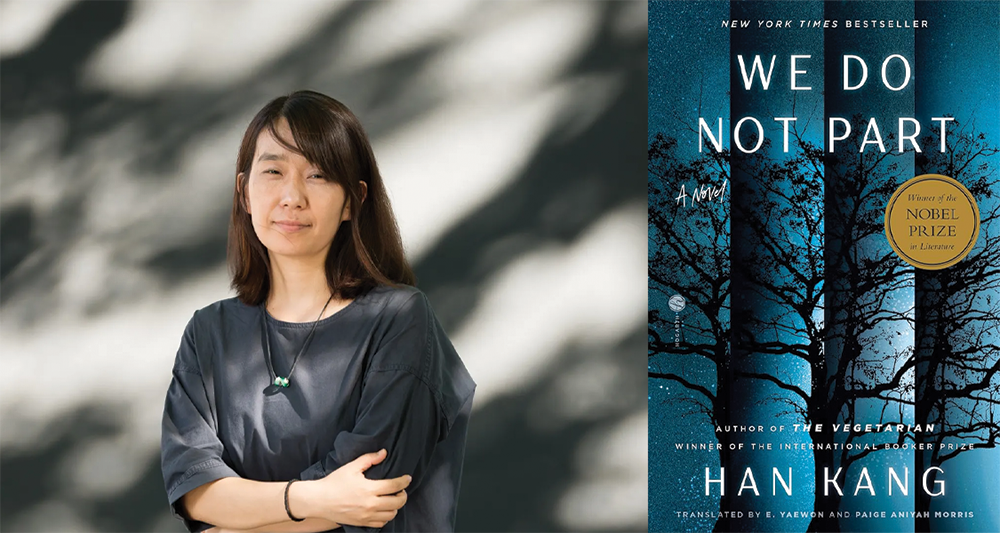

We Do Not Part by Han Kang, translated from the Korean by e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris, Hogarth, 2025

Han Kang’s latest novel, We Do Not Part, translated from the Korean by e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris, opens with a dream: Kyungha, a writer, sees thousands of black tree trunks of various heights protruding from the earth along a hill in front of her. As she walks closer, she wonders if they are gravestones. She thinks they look like thousands of men, women, and children huddling in the sparse snow coming down. Suddenly, she is wading through a body of water that gets deeper before she realizes she is at the shore and the sea is crashing in.

“When had everything begun to fall apart?” Kyungha asks herself. She thinks back to the two years before her book on the massacre in “G—” was published, when the nightmares began. Trying to shield her family–her daughter especially—from the worst of what had overwhelmed her inner world, she began to work on the book in an office 15 minutes away from her home. She tried to draw hard lines, to compartmentalize, to keep work and home as separate as possible. But sleep became impossible—days bled into nights, and nights bled into horrifying and disorienting nightmares. She hoped they might cease when the book was published, but we know now, in retrospect, that that did not happen. She is baffled by her early naivete: “having decided to write about mass killings and torture, how could I have so naively–brazenly–hoped to soon shirk off the agony of it, to so easily be bereft of its traces?”

Those violent traces have haunted her since, the dream recurring on and off in the four years since she began researching for the book. We learn that she and her friend Inseon, a documentary filmmaker and amateur woodworker, have agreed to work on a film recreating the dream. For a few years, they call each other to discuss the project, but never actually begin. Kyungha eventually tells Inseon she wants to abandon the project. They contact each other less and less frequently as time passes, and Inseon gets more and more preoccupied with the failing health and eventual death of her mother, a survivor of the midcentury massacre in Jeju. Kyungha is likewise miserable and alone. For years now, she has been dealing with episodes of debilitating migraines and abdominal pains, and has lost her job, her family, and almost all of her friends. She starts drafting her will but can’t think of one person to whom she can send it. She is barely nursing the will to live when she is roused—by a feeling of responsibility towards the person who will inevitably take up the work of executing her will after she dies—to resume living, at least long enough to get her affairs in order. “That is how death avoided me,” she tells the reader.

Then, Kyungha receives a message from Inseon, who asks her to come meet her at a hospital in Seoul. Inseon, who has sawed off the tips of two fingers on her right hand working on making the tree stumps for the project she never agreed to abandon, asks Kyungha to go to her home in Jeju to feed her bird before the day is over. So begins Kyungha’s arduous journey to her friend’s hometown, and the plunge into Inseon’s family history, the deeply unsettling history of the island, and the Korean peninsula at large.

From 1948 until 1954, following a days-long general strike and the April 3rd uprising in Jeju that called for a unified Korea and rejected US imperialism, the US and US-backed South Korean government, along with paramilitary forces, killed approximately 10% of Jeju island’s population (around 30,000 people). They also implemented a scorched-earth policy that left many of the island’s homes in ruins, most of its villages utterly decimated, and no family on the island untouched. As we learn later on in the novel, through the records that Inseon’s mother has kept hidden away in the house, many people in Jeju were shot en masse, their bodies often disposed of in nearby bodies of water. Some remains were later discovered under the tarmac of an airport runway. Some were taken prisoner and murdered later in the Bodo League massacre, and others had their remains excavated many years later from the Gyeongsan cobalt mine. This novel elucidates some of the consequences of the government’s gag order, and the struggle to find disappeared family members and uncover hidden truths.

In an interview with the Guardian, Han tells us she first discovered the Gwangju uprising and massacre—when, in 1980, in an echo of the Jeju massacre, the South Korean government violently suppressed a pro-democracy uprising—at twelve years old, in a book of memorial photographs hidden in her dad’s bookshelves. In that moment, she says, “Silently, and without fuss, some tender thing deep inside me broke.” Or, as Kyungha says: “A desolate boundary had formed between the world and me.” Months and years of research, discovered photographs and testimonies about the massacres at “G-“ and at Jeju break Kyungha over and over again in this novel. But not her alone—as she travels to Jeju, and makes her way through Inseon’s family’s archive, it seems as though every tender thing, both in her and Inseon, and in Inseon’s mom and dad, has broken. In Kyungha that tender thing continues, unrelentingly, to break.

Kyungha’s journey to Inseon’s house after she arrives on the island is difficult, and she considers giving up multiple times. There is a blizzard, the buses are barely running, her phone is about to die, the house is isolated, and the roads and trees are unrecognizable to her. On her way up to the house, she has another episode; she writhes in the snow, temporarily blinded and incapacitated. Amidst all this difficulty, which perhaps reflects the difficulty of the unearthing of local and national traumas, the truth of Kyungha’s present reality begins to escape our grasp. Kyungha’s reality and memories are interjected and interspersed with those of Ineson and her family. Happenings from this point on (has she fainted? Has she died? Has she reached the house? Is that actually Inseon speaking to her? Has the bird died?) become indistinguishable from the past, from family histories, collective memories, witness testimonies, news stories, imagined and recorded scenes, dreams, hallucinations, and reality.

This formal breaking of the novel, and the breaking Kyungha herself experiences, forces us to confront a different understanding of time, one that ebbs and flows and unfurls and crashes and bifurcates and transforms as the water that surrounds the island and crashes in on Kyungha in her dreams does—one that exists in multiple forms simultaneously, that overwhelms and drowns and swallows and quenches and carries. Han’s ability to mimic this experience of time is incredible. Her prose, in e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris’ translation, is captivating and mesmerizing. You are constantly unmoored, flowing. The lack of quotation marks and the long blocks of italicized text draw you into a trance, and the vivid descriptions of Kyungha’s dreams, the disturbing details of the massacres and the realistic recounting of Inseon’s family’s history, even as they ground you, threaten to drown you. As she speaks to Inseon in the hospital, all of a sudden:

As though someone has flicked a switch, my dream roars back, so vivid and tangible I stop breathing for a second. The squishing of my sneakers, the sponginess of the ground underfoot, the water seeping from beneath the snow. The tide rising up to my knees in the time it would take to blink, engulfing the black tree torsos, the burial mounds.

The US-funded Zionist genocide in Palestine was on my mind as I read this novel, and as I go over every underlined sentence to write this review and see my scribbled “Gaza!” in Arabic on the sides of the pages, I am reminded that it is in 1948 as well that the still-ongoing Nakba in Palestine began. And now, the genocide that began 18 months ago in Gaza continues, with over 50,000 dead and thousands more injured, maimed, under the rubble, and starving. It is impossible for me not to think of Gaza when I read about the way that the history of “G–” takes over Kyungha’s waking moments and her dreams, and seems to render everything in her present life meaningless and unbearable. It is likewise impossible not to think of Jeju, especially this month, when I open my phone and see the images and videos coming out of Gaza interspersed with posts memorializing Jeju’s 1948 uprising and its martyrs, known as the April 3 incident. It is not possible to move beyond atrocities when its perpetrators are unyielding, and when justice eludes us.

What I find both breathtaking and heartbreaking is Han’s refusal to even attempt to do so. Her insistence on remaining with the atrocities and letting them take over her characters’ lives gives life as it strips it away, because such capacity for empathy is what the suffering of our human kin creates in us, if we only allow it to. It threatens our physical and mental well-being, chips and eats away at us, and blurs the lines between us and those who suffer—it superimposes their memories and stories over our own, and allows their mourning and grief to infect our every day. It becomes practically impossible to function normally. Just as Kyungha wonders about her naivete and her expectation that she would be able to go back to her own life and leave behind the book project once it got published, Inseon says: “I’d thought when [my mother] was gone, I would finally get back to my life, [but] I realized the bridge back had disappeared. Mom wasn’t there to crawl into my room, but I still couldn’t sleep. I didn’t have to die to escape, but I still wanted to die.” As many have said since the genocide in Gaza began, and as Han makes clear: after such a breaking, there is no ‘normal’ to get back to.

Ruwa Alhayek is a Ph.D. student at Columbia University, studying Arabic poetry and translation in the department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African studies. She received her MFA from the New School in nonfiction, and is currently a social media manager at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: