The brevity of a transcendent ecopoetics, a fierce diagnosis of the contemporary art world, the psychological torture of a toxic relationship, a gathering of formidable Afro-Brazilian voices. . . This month, we are delighted to introduce fifteen new works from around the world, from the intimate to the twisted, the reverent to the radical, of healing and breaking, of what goes on within us and between us.

Apparent Breviary by Gastón Fernández, translated from the Spanish by KM Cascia, World Poetry Books, 2025

Review by Xiao Yue Shan

Rhythm in poetry, Yeats told us, serves to “prolong the moment of contemplation—the moment when we are both asleep and awake” by balancing a monotonous formula of language with the surprise of new images, ideas. In his metered perfection, he reminded us that we are innately rhythmic creatures, alive by the steady pace of breath and heartbeat, habit-forming and fond of repetition, and every interruption to this enduring pattern is a miniature shock, a fracture, a revival.

The hundred poems in Gastón Fernández’s Apparent Breviary are full of interruptions: huge, gasping chasms of silence throwing poetic rhythm into some archaic past. A few pages in, I understood why their translator, KM Cascia, had admitted that the poems made them “squirm.” They unsettled me too. With no guiding cadence to the words, no comfort of the steady pulse, with language disorientating in its skeleton arrangement, there is a sense of learning how to read again, examining each word set firmly on its own—rare stars in the page’s matte sky. Max Picard had once brought up the idea that language is too self-conscious: “each word comes more from the preceding word than from the silence and moves on more to the next word in front than to the silence.” In Fernández, this isn’t so; here, language is conscious of its origin and reverent of its silent surroundings, and as soon as one acknowledges this fact, the vacancy of the negative spaces on the page begin to seem inviting. Instead of being read as simply text, there is something of Apparent Breviary that demands to be interpreted as score, in which the nothingness is full of measures, divisions, momentum. The poet demands we notice that the emptiness is alive: it breathes.

It’s something sacred, and the breviary in the collection’s title gestures at a venerated tradition, but the poet is more interested in the behaviour of religiosity than its actual praxis; he is intrigued by how solitude cultivates the ritualization of time, how the unknown palpates and excites us, and most importantly, how absolute distinctions form between symbols and the subjects of their representation: “Lord. // The word gets lost in the / name.” Considering and then adapting the act of worship, he returns a necessary component to philosophical contemplation: distance. Instead of looking at things ever-more closely, these poems nurture separations and pathlessness, giving privacy to the mystery. They wander the elapse between what is within reach and what is beyond reach, never supposing that words can do more than simply indicate.

There is nothing beyond

the sign, the aura isopaque.

Sign. above all

things. Aura.

When facing the unknowable, we fill the spaces with what we do know—pieces of ourselves. In approaching language with a minimalist hand but an all-encompassing vision, Fernández thus creates within his sparse, firework poetry a phenomenological position to portrait our experience of memory (its flashing occurrences), the moment (briefer than seconds), knowledge (its disparate pieces), and realization (that strange, spontaneous arrival)—all these ephemeral and shapeshifting subjects which blare so brightly before disappearing. The desire to trace that disappeared form, to find that sound in silence, the need to describe what lingers in the wake of the departure. . .

Mythocracy: How Stories Shape Our Worlds by Yves Citton, translated from the French by David Broder, Verso, 2025

Review by Xiao Yue Shan

The storyteller is something of a villain. For all who have been horrified at the authoritarian weaving tales to further entrench their agenda, who are weary of corporations seizing upon narrative as the most efficacious manipulation, who remain suspicious of the curation and editorialization of reality, there is much to resent about story and its hold on us. In Mythocracy, the theorist Yves Citton spends plenty of time describing the processes by which stories penetrate our perspectives and enable our actions, fully recognizing that our unstoppable urge to invent, compile, exchange, and actualize narratives is not only innate and automatic, but that stories are the fundamental channel between public events and private perception; however, unlike similar investigations like Peter Brooks’s Seduced by Story or Christian Salmon’s Storytelling: Bewitching the Modern Mind, both of which depict the operations of narrative as deeply sinister, Citton proposes that it is now necessary for the righteous left to develop and harness the power of stories for its own political purposes.

In constructing its examination into story’s effects, Mythocracy builds significantly from the work of Baruch Spinoza, and the philosopher’s concepts of potestas and potentia. The former is the power of the authority, and the latter is the infinitely more forceful power of the multitude. Despite the fact that a leader has no power but that invested in them by their followers, the workings of our society depend on the myth of potestas and its seemingly unshakable command. From there, Citton describes the “soft power” that “consists in making others act of their own free will,“ that enables to potentia to continually invest their authority into the potestas—and this soft power is story.

With the rise of demagogues and their shockingly successful strategy of straight-up lies, Citton’s directive to the left is convincing. Stories are by their nature simplistic, as their very form rejects the complexity and simultaneity of reality, and politicians have long harnessed this reductivity to justify their positions, most of which aim not for the resolution of any issue, but the garnering of popular appeal. As the author explains:

. . . ideological myths make (partially) intelligible a tangle of causalities whose hypercomplexity always risks inhibiting any intervention. In doing so, they operate as a catalyst for political mobilisations: we act because we believe (in part wrongly) to have identified the decisive cause of a situation.

It would then seem that Mythocracy’s position articulates a simple desire for the left to simply win, but throughout, its author continually specifies that these terms do not represent any particular ideology besides that of the left’s value of equality and polyphony, and the right’s value of control and singular truth. The most desirable result would be the use of narrative to imagine alternative ways of living that resemble the way we want to live, and to make them real enough to us that we are willing to take action to rescue those worlds from the realm of fiction. In doing so, we reassert the individual capacity of the potentia “to produce counter-conducts, counter-stories, and counterinterpretations.”

The distinction between reality and fiction conveniently ignores the many intersections by which the two inform, supplant, and disguise one another, because human reality is composed of individuals who fictionalize. Citton’s illuminating and meticulous volume incorporates neurology, anthropology, linguistics, history, and philology to trace the ways in which narratives travel and develop in order to build our civilizations, investing itself in its conviction that stories are necessary—and inescapable. We might as well use them to do some good.

Applause for a Cloud by Sayumi Kamakura, translated from the Japanese by James Shea, Black Ocean, 2025

Review by Dan Shurley

When distraction is a way of life—as it is in our increasingly techno-authoritarian realm—paying attention is a radical act. With Applause for a Cloud, Sayumi Kamakura stages her quiet rebellion with nothing more than cherry blossoms, clouds, and wind. From early on in this bilingual collection, the celebrated haiku writer invites us to slow down, to appreciate the beauty of nature and make ourselves at home in her enchanted world:

This is a swaying

water lily leaf—

won’t you take a seat?

Who exactly is speaking here? And who is being addressed? The water lily? A frog? The poet? As translator James Shea notes, Japanese haiku “omit pronouns, do not distinguish between singular and plural nouns, and allow more syntactic flexibility than English poetry”; with this same approach, he preserves the ambiguities that allow Kamakura to blend subjectivities, creating a feeling of cosmic awareness that transcends the consciousness of any individual entity.

Perhaps the most traditional function of haiku is to mark the start or close of a season, and Applause abounds with these seasonal words—though often salting them with deadpan wit: “‘Summer’s over’/ mutters a goblin/ in the tree crotch.” Another way Kamakura subverts traditions is via animism rather than the haiku’s customary associations with Buddhism. Here, nature possesses agency and intent: There’s “the camellia flower” that “wants to drop/ next to that man”—a pungent image given the blossom’s traditional association with decapitation in Japanese culture.

A distinctive formal feature of the collection is its arrangement of haiku in groups of three, creating what might be read as triptychs or montages. Consider this sequence:

Passing through/ the hole of a donut,/ summer continues

A bee plays in juice/ and drowns/ before too long

Which grain of sand/ disappeared alone/ into the desert?

There’s no obvious connection between these three pieces—summer passing through the hole of a donut, the doomed pleasure-seeking bee, and the ascetic grain of sand who goes off on a vision quest in the desert—but they invite readers to make their own disjunctive links in a call to renga, the literary game from which haiku originated.

Despite these thematic associations, It isn’t until the book’s third section, “Clouds,” that a narrative emerges and the most personally revealing haiku appear: “Like stars to the night,/ my husband/ tied to tubes.” Kamakura, in her role as “the wife,” mourns her husband’s absence with powerful restraint: “In the hollow/ of your pillow—/ the dream again.”

With their careful attention to daily life and cyclical time, these bright, elegantly translated haiku remind us that brevity need not mean haste, and that attention, properly paid and framed with generous whitespace, remains our most sophisticated technology.

Someone to Watch Over You by Kumi Kimura, translated from the Japanese by Yuki Tejima, Pushkin Press, 2025

Review by Eric Bies

Yuki Tejima’s limpid translation of Someone to Watch Over You marks the English debut of Kumi Kimura, a two-time nominee for Japan’s prestigious Akutagawa Prize. Kimura’s novel is a slim thing—a small-town tale about memory and guilt—but it offers a compelling picture of an improbable relationship.

Taking place in Iwate prefecture, some five hundred kilometers northeast of Tokyo, the novel is set in the early weeks and months of the COVID-19 pandemic (though Kimura never names the virus outright, characters wear masks, vigorously wash hands, and disinfect groceries). The story centers on Tae, a lonely, anxious, somewhat paranoid former schoolteacher. At forty-six, having returned from Tokyo to watch over her parents, she now lives alone in the house that had belonged to them, who are both dead at the outset of the novel.

All of this presents the promising gambit of a woman who, provisioned with a modest inheritance, has everything she needs except human connection. The exigencies of a lockdown complicate the matter, but Tae doesn’t need a pandemic to be skittish about people. The death of one of her students, a decade past, continues to haunts her, and when an old man in the neighborhood dies under mysterious circumstances—murder? suicide? the virus?—Tae can’t help but assume that her presence in town precipitated it.

She’s a bit superstitious, but she’s also practical. When her shower drain clogs, she arranges for a young, local handyman—Shinobu, who’s a bit of a wanderer and a loser—to unclog it. Excluding a few expository flashbacks, the novel alternates between Tae and Shinobu’s points of view, largely in real time. Most of these transitions are seamless; other sections, imbricated like roofing tile, punctuate the book with comic irony, much of its charm banking on the fundamental contrast of a difference of minds. Though neither knows it at the time, a clogged drain won’t be the last incident to draw them together. It might even dawn on Shinobu, who contends with his own dark past, that he needs Tae as much as Tae needs him.

Kimura skillfully establishes a delicate tension between her two protagonists—precisely the kind that has always characterized the sometimes awkward, sometimes revelatory unfolding of a relationship between total strangers. Someone to Watch Over You may not offer any meet-cutes or satisfy any explicitly erotic criteria, but the complicated relationship at its core feels real. It’s a novel of and for our complicated times.

Wickerwork by Christian Lehnert, translated from the German by Richard Sieburth, Archipelago Books, 2025

Review by Eric Bies

Christian Lehnert, the author of eight volumes of poetry in German, makes his English debut in Wickerwork. The collection ranges over the output of a decade, gathering roughly a hundred-thirty poems, disclosing roughly a poem a page, with most of them being the briefest of texts; the majority make their mark in all of two lines, and their subject matter is nominally narrow as well. There’s a poem about a salamander, a poem about a butterfly, a poem about a tree, a poem about a flower—even a poem about an amoeba:

What turns up outside / be it substance or reflection /

Flows around the cell / its pseudopod extended / in affection.

The rhyme is preserved from German (as is the same for virtually all the poems)—and those forward-slashes aren’t line breaks. Lehnert’s punctuation is as conspicuously unconventional as Emily Dickinson’s, doing for the virgule what hers did for the em dash. In Lehnert’s hands, the mark is a kind of repeating saber slash, offering further divisions of rhythm and sense. It might just be the next best thing to a comma, which, anyway, for more than half the book’s length, Lehnert does without entirely.

It’s this first half, too, that feels most alive, justifying the collection on the strength of its quiet precision alone. In two-line poems about seed pods, fungus, geese, plankton, and moths, Lehnert’s spare style makes its most memorable strides. (To say a couplet strides at all might sound like a stretch, but these poems stick in memory with all the distinction of a classic epigram.) In writing about nature, Lehnert looks past lions and wildebeests to exalt the smaller stuff, and when he writes, for instance, of red wood ants (“Their nest extends / the full length of the branch [/] That breaks / handing the ants / over to chance.”), he immediately designates himself as trustworthy a guide to the universe as Francis Ponge. Such poets possess what can’t be faked: a wise, cosmic humor, and a keen sense of proportion.

Line by line, Richard Sieburth’s translation is the epitome of graceful economy. These poems effortlessly intuit just the kind of spiritual dimension known by anyone who’s stood in awe of nature. And those who know will know that it need not be a Niagara. This is the epic opposite of epic poetry, and that is a kind of miracle.

Covert Joy by Clarice Lispector, translated from the Portuguese by Katrina Dodson, New Directions, 2024

Review by Ben Goldman

Any selection is a kind of culling. In New Directions’ latest Clarice Lispector offering, one might lament the absence of any one of the eighty-five tales translated by Katrina Dodson in the 2018 Collected Stories (personally, I miss “One Hundred Years of Forgiveness”). Nonetheless, the nineteen that comprise Covert Joy form an excellent gathering of some of her most recognized stories and act as the foil to her longer work; though they are also intensely inflected with the numinousness of the inarticulate instant and the climactic recognition of the unperceived, in their groundedness they depict even more intensely the gushing out of such elements from the quotidian—the life of objects, duty, routine.

This difference between short- and long-form is perhaps illustrated most strongly in the final story of this selection, “That’s Where I’m Going,” because it unspools in Lispector’s novelistic mode, closer to an intimate philosophy than to narrative:

Yes, I’m going. And I’ll return to see how things are. Whether they’re still magic. Reality? I await you all. That’s where I’m going . . . At the edge of I is me. To me is where I’m going. And from me I go out to see. See what? to see what exists. After I am dead to reality is where I’m going.

Most of the other stories in Covert Joy situate themselves in the realm of the prehensile; Lispector finds a way to enter the mystical from the ground up. Note the difference in a story like “The Foreign Legion”:

The chick, it kept peeping. On the polished table it didn’t venture a step, a movement, it peeped inwardly. I didn’t even know where there was room for all that terror in a thing made only of feathers. Feathers covering what? a half dozen bones that had come together weakly for what? for the peeping of a terror.

For me, it is in the angle of approach of this latter example that I feel the power of Lispector’s visionary prose most acutely. If in “Love” she writes that “the cruelty of the world was tranquil,” the abstraction takes on an imagistic meaning—for the tram has lurched and Ana has dropped her knit sack, smashing the eggs. The stories remain as ontologically and cosmologically motivated as the major novels, yet they narrate us into the kind of transubstantiation that Agua Viva and The Passion According to G.H. are perhaps meant to already be. Both induce wonder, but the stories make me feel like I myself am “that tiniest point of surprise lodged in the depths of [Ana’s] eyes.”

Theory of the Rearguard: How to Survive Contemporary Art (And Almost Everything Else) by Iván de la Nuez, translated from the Spanish by Ellen Jones, Seven Stories Press, 2025

Review by Xiao Yue Shan

It’s difficult to talk about Peter Bürger’s The Theory of the Avant-Garde without feeling like one is reissuing the obvious. Of course the aesthetic inventions of a hundred years ago felt truly radical. Of course the breaking-up with the institution of art itself was a first. Of course everything that followed has been tinted by that failure. It’s good then, that we have Iván de la Nuez’s Theory of the Rearguard, which takes over from Bürger’s work without reiterating it and its dismays. If the purpose of the avant-garde was to dissolute any barrier between art and life, the rearguard is written here as a construct of art and survival. It is the survival of art, of the imagination, of humanist endeavor, of the global industry, but ultimately, de la Nuez asks that we take this word at its base definition, as a mode of being instead of an abstraction; survival is a truncated vision of life, where the future shrinks into the immediate. How does contemporary art live on, then, in this miniaturized vacuum of desperation and uncertainty, constantly ruminating on its own mortality?

Chronology is a strange dictator. Once the avant-garde was institutionalized as a movement with a beginning and an end, and the whole concept of going beyond the present was firmly located in the past, the question of the future is left in a slow dissolve. With the contemporary implicated in this impossible contradiction, de la Nuez ascribes a telling panic to our instinct for creation and expression. In his words, the artist must “moonwalk”: go backwards while pretending to go forwards. Art now enjoys a tremendous distance from life through its immensely profitable insistence on its own necessity, and yet to provide evidence of this importance, it must still continue to engage life, to follow its motions and entertain it—by any means necessary. After the avant-garde, the deluge, and Theory of the Rearguard expresses a knowing resentment with how contemporary art now thoughtlessly adopts life, in politics and in brands, in technologies and rhetorics, gorging on its own excesses and seeking any possible way to remain with us, to be admired and confided in by us—but then fleeing from us to take haven in the collector’s archive and the insatiable museum.

Art has always made of itself as salvation, and it’s true—it saves us. (Even the most cynical can admit this; that’s why even the most sardonic critics continue to put out Theories.) Contemporary art, however, wants to readjust that faith: it’s not going to fix the world, but it will offer us sustenance through to the very next moment. In its regard, the present is an ever-quickening series of disappearances and discoveries, and de la Nuez states that in following it, “we are assembling the aesthetic advance of a politics that needs to legitimize itself and an economy that needs to impose itself.” It’s a great line, and demonstrates much of his brilliance—as well as the equal acuity of translator Ellen Jones: clean summation, casual expertise, earned confidence. As an accomplished curator and critic, he brings a winking insider’s view to the dramatics of contemporary art’s lapses and dying sputters, condemning its vacuous edifices while still continuing to search for meaning and necessity. That’s survival instinct.

For its ninety-odd pages, Theory of the Rearguard is filled with enclosed sparks of pointed diagnosis, told with charismatic humor and an insistence on seeing through the bullshit, but there is a discursiveness and a crowded nature to its multitude of ideas, which rarely breathe for more than a couple pages before the next comes along—from the falsity of multiculturalism to the atomized city, from photography and reproduced truth to artist-writer pairings: fragments in correspondence with our amorphous and duplicitous reality. De la Nuez is a gifted aphorist, and one suspects a delightful conversationalist, full of notes and stories and references, and as such the book resembles more a fireworks show than an enduring luminosity—but perhaps this simply mirrors how brevity is now the essence of our modern experience: “The fact is that we do not produce artefacts or ideas, machinery or works of art that compete on the market of durability, but rather on the market of transience.”

stay with me by Hanne Ørstavik, translated from the Norwegian by Martin Aitken, Archipelago Books, 2025

Review by Liliana Torpey

The readers who are unable to relate to Hanne Ørstavik’s unnamed first-person narrator in stay with me would be the lucky few. In a flowing and immersive narration, the author reveals a warped and desperate logic as her protagonist, at fifty-two years old, becomes hopelessly attached to M, a man seventeen years her junior. M is hot and cold with volatile rage, while the narrator is unable to close out the day without several drinks. Together, they forge a precarious attachment, one that leaves the narrator constantly on edge and afraid. But afraid that M will leave, that he will hurt her, or both?

While their problematic romance occupies the center of the novel, the story is framed by the narrator’s childhood, spent with a punishing and explosive father. She knows this is the root of her fear and perhaps also of her deep desire for connection—something she’ll pursue at any cost. This fact frustrates the reader, who will want her to take that knowledge and run, leaving M in the dust, but the narrator is precise in her thought process, however convoluted it may appear: “. . . knowing never helped. I’ve known all along. I’ve just never known what to do about it.” As exasperating as it is to watch someone get stuck in a seemingly simple knot, I’d wager most of us have been in that place, with a clear view of our predicament and not a clue how to escape it.

A writer herself, the narrator works through her dilemma by creating her own novel. This novel’s protagonist, Judith, is also in her fifties and beginning a relationship with someone younger—in her case, a highschooler of “seventeen, eighteen” years old. While Judith seems to serve a purpose for the narrator, her purpose for the reader is questionable. Scenes from this meta-novel are sparse, and Judith’s involvement with a teenager renders her loneliness unsympathetic. While stay with me engages with the child within us—the one full of both wonder and fear—these sections bring to mind the question of the adult’s choices to either reduce or remediate harm.

While it is painful to watch Ørstavik’s protagonist suffer and struggle, her valiant efforts to understand herself are spilled vulnerably across the pages, until she feels ready to make a different choice—to “shift [her] gaze,” and embrace herself, rather than running herself ragged for those who only reject and diminish her. The meta-asides and agony that lead up to this moment do not make its arrival any less revelatory or refreshing.

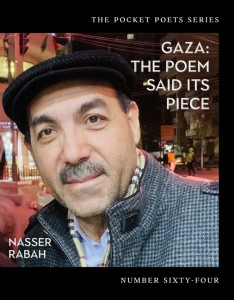

Gaza: The Poem Said Its Piece by Nasser Rabah, translated from the Arabic by Ammiel Alcalay, Emna Zghal, and Khaled Al-Hilli, City Lights, 2025

Review by Liliana Torpey

“. . . we meet in the garden of madness,” Nasser Rabah writes, “when luck struck once.” We too are lucky to meet Rabah’s first collected works translated into English, as madness rages all around. Throughout this varied and transforming compilation, Rabah’s lines devastate: “I save their ball for the kids for after the war. They might return with no legs”; and they sing: “Your fingers will be the fruit of orange trees, your arm the staff for a victorious flag, and you heart the train’s last station. . .”

Gaza: The Poem Said Its Piece includes poems written before and during Israel’s most recent assault. Rabah is compelled to write even when words seem insufficient, when they succeed only in obscuring the purity of sorrow, rage, and joy. Still, he continually struggles with his craft’s urgency, offering words at the altar of life while simultaneously recognizing their frailty and dependence on an invisible listener—be it God, a reader, a dead friend. “The heart doctor treating me now recommends only one thing. . .” he writes: “stop writing the diaries of a dead village.”

In their afterword, translators Ammiel Alcalay, Emna Zghal, and Khaled Al-Hilli speak to the long and slow process of learning to read Rabah’s poems, of allowing the poems to teach them. In their translations, they’ve specifically accommodated the “non-understanding” evoked by Rabah’s poems, which are searching, glitteringly tactile, and intuitive in their movements; often it seems that Rabah is following the poems, rather than the other way around. I, too, felt compelled to shift into an intuitive posture to feel along the poems’ features as I read:

O Kids, do your best—when I’m asleep—to laugh as loud as

watermelon, to wake me up from the nightmare, and realize

I’m not a wall passersby hang their worn-out days on.

Illuminating and lamenting the bewilderment of war and destruction, these poems expose what is shocking and what is banal: the dazzling presence of luck, bombed buildings which still stand, and “beautiful doubt.” Meanwhile, memories and old loves are forgotten in favor of surviving another day. While some may question how such grand scales of violence may be endured, Rabah carves space for the heart with an exquisite and excruciating attentiveness—even when it turns to stone, becomes “a plaza of ash,” or “flutters like a spinning coin.” The heart is present, always, everywhere, even destroyed, cold, and hardened; it works its way through the poet’s fingers to write.

Water by Rumi, translated from the Persian by Haleh Liza Gafori, New York Review Books, 2025

Review by Eric Bies

2022 saw the publication of Gold, Haleh Liza Gafori’s first book of translations of poems by the thirteenth-century Persian poet, Rumi. Now comes Water, a companion volume, and the similarities between the works suggests that the two should be read one after the other. Both contain precisely fifty-four poems. Both crystallize—and diverge—along certain thematic lines. “Gold highlights Rumi’s rhapsodic, ecstatic side,” Gafori writes in her introduction. “Water, by contrast, is Gold’s moody cousin.”

It’s an apt distinction. Poke a finger at random into Gold and you run the risk of electric shock, landing on lines that vibrate to “the booming voice of the heavens.” Water’s mood is, well, earthier—no less spiritually inclined, but decisively grounded. Still, the two books overlap significantly in substance, and that’s a good thing; one can simply never have too much Rumi. Eight centuries separate his world from our own, but his poems are as modern as they come—not because they sound like they were written last week, but because they speak to the head and the heart, no matter the era.

Those who’ve encountered him in any of the popular anthologies (think Coleman Barks’ landmark collection, The Essential Rumi) will find a similar combination of styles and concerns in Gafori’s versions: lines that are personal and direct, spiritual but not religious, sincere while steering clear of sentimentality. Virtually every one of the book’s poems qualifies for the role of representative quotation. Here’s a short one: “When I leave this body, / people will ask— / what did he do with his life? // I knew you, Beloved. / That was enough.”

Rumi’s sensibility proves particularly congenial to readers who’ve struggled with other kinds of poetry, especially the more experimental stuff. There’s nothing cloying, cutesy, covert, or coded about these works. This is hardly to call his arrangements artless; rather, his candor disarms. While one is never in a bind to crack a cipher, one is frequently toe-to-toe with a consciousness that demands as it consoles, confronts as it exalts, courts as it recedes. Gafori’s marvelous sensitivity to rhythm elevates all of these qualities to the canonical level at which good work may last. Her poems flow and meander from one object of affection and attention to the next; the well-loved reader is only bound to wish there were more.

Contemporary Afro-Brazilian Short Fiction, edited by Ana Cláudia Suriani da Silva, Julio Ludemir, and Maria Aparecida Andrade Salgueiro, University College London Press, 2025

Review by Dan Shurley

“Rayanne is a Rio girl,” writes Geovani Martins in his story “Landless in the Sea,” invoking with this opening gambit a celebrated Caetano Veloso tune, while subtly subverting the image of the beach-loving Carioca that such songs have helped construct. For one thing, Rayanne is “a sem-terrinha,” a child of activists from the Landless Workers Movement; she lives in Rio’s distant outskirts, and has never been to the beach. When her family finally ventures to Ipanema Beach (one “for rich people”), their presence itself is a political act, and the reaction is predictable; the group is suspected of fomenting a “flash robbery,” police surround them, and students briefly shout their support before hurrying back to “finish a sociology paper.” Yet amid this hysteria, Rayanne still finds her glorious moment in the sea.

In just a few pages, Martins, who grew up in Rayanne’s Rio, encapsulates Brazil’s fraught social landscape, where race and class divisions simmer at the surface. This theme of boundary-crossing—what happens when the barriers of Brazil’s racialized hierarchy are traversed—runs through Contemporary Afro-Brazilian Short Fiction, an ambitious anthology that aims to raise the profile of Black writers from a country with the largest population of African-descended people outside Africa itself, but whose literary achievements have rarely been recognized.

The collection grew out of translation workshops conducted at Festa Literária das Periferias (FLUP), a literary festival staged on the outskirts of Brazil’s traditional cultural spaces, and brings together multiple generations of Black Brazilian writers. From celebrated novelist Conceição Evaristo comes “Dancer’s Feet,” about a performer who escapes the favela but forgets his origins, only to receive a haunting reminder—possibly a curse—from three Black elders. From the emerging writer Denise Homem, we have the allegorical “Brazilian Citizen,” which follows a writer whose favela diaries gain acclaim. The writer sees her star rise steadily—until she discovers that her publishers are plotting to sell her film rights without fair compensation. She then makes a radical choice to withdraw all authorizations for her work and retreat to a farm, where she lives happily ever after. One imagines Percival Everett chuckling his approval.

The anthology is guided by what critic Eduardo de Assis Duarte terms “friction-fiction”: texts that remain “in permanent friction with the status quo.” Many stories offer glimpses into Rio’s marginalized communities, including its queer scenes, where characters navigate precarious existences with swagger to spare; elsewhere, the “friction” often manifests as paranoia, self-doubt, and despair, particularly in the stories set in favelas, where characters walk a tightrope between gang violence and police brutality. Yet these writers deliberately avoid sensationalized portrayals of Black gangsters and crime, which, as the editors note, would only reaffirm stereotypes linking Blackness with criminality. Instead, by centering the experiences of the victims of violence, these writers reclaim narrative agency and complexity for their Black protagonists—fulfilling the editors’ broader project to reorient these contributions toward the global African diaspora.

If the anthology tends on the whole toward didacticism, its overt sociological commentary is leavened by its stylistic variety. Esmeraldo Ribeiro’s surrealist gem “Mirror Women” cruises under the radar of direct confrontation with the dominant culture, instead generating friction through formal experimentation and symbolic complexity. With its cryptic poetry, multiplicity of marginalized women’s voices, and retroactive framing device calling to mind Poe’s supernatural tales [!], it represents a more subtle challenge to literary convention—and one that rewards careful rereading.

Ultimately, what emerges from these stories is a collective portrait of Black Brazil that, despite occasional translational infelicities, makes good on the anthology’s ambition with bitter irony and verve.

Gloria by Andrés Felipe Solano, translated from the Spanish by Will Vanderhyden, Counterpoint Press, 2025

Review by Liliana Torpey

My mom once told me, while looking at black and white photographs of my grandmother and her family, that in Colombia, street photographers used to snap candid portraits of well-dressed urbanites walking the city; afterwards, they’d hand their subject a card of some kind, which could be taken to a developer to purchase the photo. The cover of Gloria, shot by renowned photographer Gary Winogrand, recalls this practice—if it were adapted to the gritty streets of 1970s New York City. The photo’s subject, a visual stand-in for the novel’s protagonist, is caught in an eternal stroll, hair floating in the gust of her stride, embodying a youthful grace.

Like its cover, Gloria is a portrait of a young woman finding her way. The narrative primarily follows her over a single day in Spring of 1970: before, during, and after witnessing Argentine singer Sandro’s performance at Madison Square Garden—the first Latin American artist to take that stage. This is the day, the narrator tells us, that “Gloria was Gloria for the first time.” We are then given momentary glimpses into other stages of her life, including childhood, marriage, infidelity, motherhood, and career changes—but the focus returns always to this eternal present: Gloria waiting for her temperamental boyfriend Tigre to show up, Gloria walking to a Times Square diner with her friends, Gloria wondering whether or not to follow through with Sunday’s plans. We also peer into the background that gives texture to these everyday events: her father’s murder during the height of political violence in Colombia, and her stoic mother whose disinterest wounds her.

However, each memory and aside feels ephemeral, ungrounded, emerging like an incandescent bubble before drifting curiously away. The connective threads between past, present, and future are faint, weaving a web of unclear meanings and indistinct relationships. Eventually, the story is revealed to be narrated by Gloria’s son, but his identity is equally watery, their relationship vaguely articulated. At 154 pages, Gloria resembles the other art forms it references—photography and music—more than a novel. It captures the lightness, the wonder, the refreshing breath of youth’s horizon. Like a melody, it leaves an impression but with a light touch; like a photograph, it captures its subject’s essence but not her wholeness or true depth. As I read, I saw her clearly before me, but couldn’t quite grasp where she’s been, or where she’s going—much like the way we meet pretty much everyone, in the middle of their lives.

The Mountains of Kong by Dag T. Straumsvåg, translated from the Norwegian by Robert Hedin and Dag T. Straumsvåg, Assembly Press, 2025

Review by Dan Shurley

A disease runs off with a medical specialist, provoking jealousy in the patient. A discarded child’s shoe sprouts first a foot, then a leg, before burrowing back into the cobblestone. A couple, themselves incapable of crying, engage a man to serve as “the surrogate mother of their tears”—with surprising success. In The Mountains of Kong, an amusingly maladjusted collection of prose poems by the underrated Dag T. Straumsvåg, objects lead autonomous lives, and the inexorable decline of the body and mind inspires paranoia and laughter in equal measures.

The volume arrives in a bilingual edition from Canada-based Assembly Press, with Robert Hedin’s unobtrusive and finely crafted translations placed alongside the Nynorsk. Spanning two decades of consistent work by the Norwegian poet, the poems present a wide range of subjects in various states of dislocation and disillusionment. The more active pieces read as highly compressed micro-narratives that rely on defamiliarization to highlight the absurdity of life—all within highly regulated syntax. In a piece called “Retired Private Detective,” the protagonist, disturbed by his aging body, launches an investigation into himself—a premise that spirals into wild speculation.

He could hear this sound deep inside himself, a munching sound, like someone gnawing on a leg bone. He suspects his ex-wife, then his neighbor. A few months later he begins to limp. Maybe the limp was planted there. He moves to another city, changes his name. He can still hear the munching. He grows older. He grows shorter. He suspects everyone. People die and leave him trinkets in their wills. Other parts of him go limp. He loses his hair. He investigates himself. Each morning he wakes to a silvery plane buzzing out of the sun, dropping breakfast in his mouth without spilling.

This is the psychological terrain mapped out by Dostoyevsky, Gogol, Kafka, and, thrillingly, the obscure Soviet absurdist Daniil Kharms, whom Straumsvåg has cited as an influence. Elsewhere, Lewis Carroll comes to mind, but the people on the other side of Straumsvåg’s looking glass appear just as miserable and disappointed by life as those peering through it. Still, the poems are funny even in their bleakest moments, deriving their liveliness from the daily bread of the imagination.

A Girl Is Lost in Her Century, Looking for Her Father by Gonçalo M. Tavares, translated from the Portuguese by Daniel Hahn, Dalkey Archive Press, 2025

Review by Liliana Torpey

“Chance, what happened to him, defined his path; as if the outside world was in control of him, as if his destination was not within him, but within each person he encountered,” writes Gonçalo M. Tavares of his protagonist. “Wherever they take me, I go.” A Girl Is Lost in Her Century, Looking for Her Father begins when this aimless fellow, Marius, meets Hannah, a fourteen-year-old girl with Down syndrome, on the street; as can be surmised from the title, she is looking for her father. Hoping to deliver her to a safe, familiar person, Marius then accompanies Hannah to Berlin—where she says they might find him; without any resistance on his part, Hannah’s goal becomes his goal.

Rather than an actual search for Hannah’s father, however, the novel follows the various people (mostly men) the pair meets along the way, each of whom profess bizarre and loyal obsessions: an antique collector carries on the patrilineal tradition of recording consecutive even numbers into a series of notebooks every day; a man in their motel repeatedly plays the musical notes found in a destroyed archive on the piano; and so on, with increasingly unexpected characters and customs. These preoccupations allow each individual to create protected, internal universes, detaching their attentions from the horrific events of the war or preserving their intellect for posterity. A kind of postwar echolalia consumes these characters, and Marius floats from one to another. Like scattered north stars, they draw him in.

Hannah’s character appears to serve primarily as a framing mechanism for Marius’s explorations, her condition mirroring the other characters’ vulnerabilities. “Marius thought about how hard that was, not just for someone with a learning disability, but for all human beings, for all living things—to ‘indicate which part of your body hurts.’” The kinship between the two grows based on their shared sense of disorientation as two lost souls, yet Hannah’s own story is marginal, her interiority unknown—supposedly due to her disability, though perhaps also because of some traumatic event related to her father’s disappearance.

Through consecutive encounters between alienated minds, stripped of any collective meaning by the sweeping events of their era, Tavares’s fiction offers a philosophical study of a time when very few true purposes remain viable. In this tumult, A Girl Is Lost details the many absurd ways individuals fulfill their rational need for purpose, nurturing strange and idiosyncratic passions, channeling their imagination and attention in disparate directions—though few of them, if any, lead away from loneliness.

The Night Trembles by Nadia Terranova, translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein, Seven Stories Press, 2025

Review by Liliana Torpey

When an earthquake arrives on the night of December 27, 1908, it strikes both shores along the Strait of Messina. On the Calabrian side, Nicola, an eleven-year-old boy, feels the earth tremble while tied to his bed; he’s been locked in the cellar by his mother, who claims to be hiding him from the devil. In Messina, Sicily, Barbara collapses along with her balcony while ruminating on how to break free from her controlling father, who has promised her hand to a stranger. The earthquake destroys everything: buildings, limbs, families, the concept of family entirely. Nicola and Barbara survive, while their guardians either perish or disappear in the chaos.

Naida Terranova’s novel viscerally captures the sharp realities of a world undone, while holding fast to the terrifying opportunity that the disaster offers both Nicola and Barbara—a new life salvaged from the rubble. “I was free in a frightening and irreversible way, and I had to use that gift before it used me,” says Barbara. Tragically, however, it is impossible to parse their freedom from annihilation. When Barbara later suffers a shocking assault by a sailor delivering aid—a scene that Nicola witnesses, they are both indelibly marked. “Of all the splinters that were still falling on my city,” recounts Barbara afterwards, “I had not avoided the sharpest.”

The Night Trembles exposes the structures of power and patriarchy that remain firm as physical architecture crumbles, skillfully illustrating how the disarray of disaster is used to reassert existing power dynamics. And yet it is full of grit and tenderness; Nicola and Barbara create what they can with what they have, building chosen families that break from their biological ones, creating systems of protection and care.

Each chapter is named after a major arcanum of the tarot, and a brief explanation accompanies each symbol. The chapter “Temperance,” for example, offers a lesson embodied by the figure on that card: “Is he not the one who bears the good news that beyond the duality of ‘either-or’ there is—or is possible—still that of ‘not only-but also’ or ‘both-and?’” The novel embraces this ethos. In Barbara and Nicola’s story, catastrophe does not offer silver linings; rather, rupture reveals how many lives are indeed possible, and, for an instant, it tosses those possibilities into the air. Some hit you on the way down, while others you can catch if you are quick enough.

Eric Bies is a high school English teacher. His writing has appeared in World Literature Today, Rain Taxi, Full Stop, Open Letters Review, and many other places. He lives in Southern California.

Ben Goldman is a writer based in Belgium. His work can be found in Washington Square Review, Sonora Review, and Words Without Borders.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet, writer, editor, and translator.

Dan Shurley is a writer and journalist in Philadelphia. His fiction, poetry, and criticism have appeared in Granta, BOMB, the TLS, the LA Review of Books, and a few other places. His writing on Indigenous cultural erasure in Philadelphia has been cited by the American Library Association.

Liliana Torpey is a writer and translator from Oakland, CA. Her work has appeared in The Rumpus, NACLA, and Euronews Culture. She is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at San Francisco State University.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: