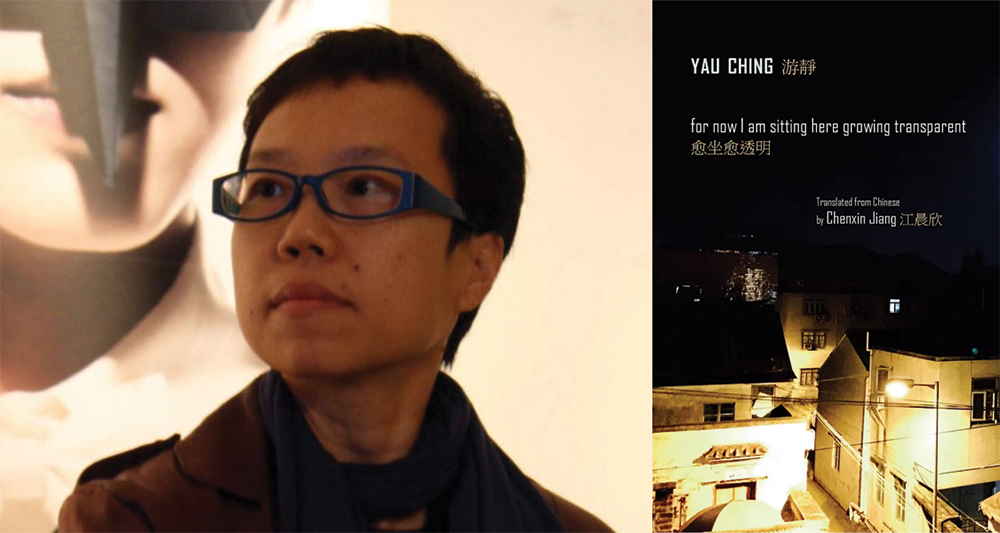

for now I am sitting here growing transparent by Yau Ching, translated from the Chinese by Chenxin Jiang, Zephyr Press, 2025

In the poems of Yau Ching’s For now I am sitting here growing transparent, there is a longing, on the part of the poet, to engage with literature for its own sake. She declares that: “I’ve always liked the idea of reading in bed, a life spent / falling asleep reading waking up / and reading more . . . / I only ever write on assignment / my life is ten cents per word no pay no words.” Exemplifying how Yau uses softness and vulnerability in the stead of impassioned critique, readers are likely to find themselves entranced by these poems, their fiercely gentle existence outside of social hierarchy. The resulting text is both relatable and transformative.

Translated from Chinese and published by Zephyr Press, For now I am sitting here growing transparent is Yau’s fifteenth book, and her first to be translated into English. Gathering work from Yau’s other collections, this text is a kind of mid-career retrospective, making Yau’s work accessible to English-speaking audiences while also curating the most resonant and crafted poems from her corpus. These poems have been gathered and treated with great care by translator Chenxin Jiang, whose introduction foregrounds the reader in both the social and political context of Yau’s subtle poems, as well as their linguistic deftness and adventurousness, showcasing the enduring relationship between these two creatives. Admitting that Yau’s poetry provides a challenge due to its “wordplay and playfulness with form,” Jiang nevertheless comes up with solutions that match the idiosyncrasy of the originals.

Delicately understated yet full of Yau’s queer and feminist politics, this compilation is both ideologically and formally explorative, refusing to fall into the neat category of confessional poetry—or conversely, of explicitly political content. It also includes still images from the author’s film and video projects, creating a haunting multimedia experience reminiscent of mid-2000s zine culture as well as today’s visual-art-centered literary magazines, maintaining a deep stylistic relevance to ongoing social aesthetics.

The collection begins with a declaration of nonbelonging: “We are orphans / who don’t belong in Asia / neighborless friendless unbrothered . . . / This, then, is Eden.” Interpreted through a classically queer reading, this could be a liberationist statement—finding meaning in alienation and placelessness—but the lines also resonate as a beautifully cynical critique of futurism. In describing “Eden” as oppressive and isolating, Yau questions the very idea of a perfect or ideal future. Her fearless rejection of futurity calls to mind the anarcho-nihilism of the BashBack influenced journal baedan—which uses the concept of time travel to criticize the concept of civilization—or other such zine projects at the intersection of radical politics and poetry. For Yau, traditional symbols of status are meaningless in the face of actual community and all its glorious imperfection and disorder.

Yau then goes on to describe the physical harms caused by oppression, a personally experienced ordeal given her experience living and teaching poetry in Hong Kong amidst the nation’s intense political exchanges: “When I finally fled / the box called Hong Kong / my sensitivities were deadened / health itself is just numbness.” Given the Covid pandemic and the onslaught of AAPI hate that followed, this look at public health could not be more urgent, especially for English-speaking audiences who may be all too willing to forget the struggles, desires, and humanity of communities in China and Hong Kong. In Yau’s view, it is always the most marginalized people, such as residents of Hong Kong, whose health problems are ignored by institutions, whose intuition and somatic senses go dormant due to constant invalidation, and who are blamed for the public health issues that harm them most. According to Jiang, even the language itself is a site of oppression; in her foreword describing her process, she comments on Yau’s “insistence that standard Chinese is not her own language—and indeed, the Cantonese inflection . . . makes her point.” In Yau’s poetry, even the body and voice are contested territory, as is language and its intersection with culture—but this also leads to the implication that embodiment and language can be liberatory in and of themselves.

Narrowing down from the societal view, many of Yau’s poems also explore her most prevalent themes—such as that of nonbelonging—from a more personal standpoint. In “No City,” she writes: “Whenever I go to a new place / I think about settling down / I’m looking for what I imagine / the thinkable cannot be done.” The speaker here simultaneously possesses a deep drive for exploration and a longing for stability, yet knows that neither can offer an authentic mode of being. Having shown her film projects in German, Japan, France, and beyond, Yau is both a citizen of the world and inextricably rooted in the context of Hong Kong; her poetry mirrors this generative liminality, displacing both her attachment to place and her equally intense desire for novelty and translocal community.

Similar to the first poem, “No City” finds a paradoxical sense of home in marginalization and placelessness, acknowledging the dualities of experience. Later poems then see her as “torn between grief and nihilism” as she probes a sense of loss, but all the while, she continues to take a gentle, non-confrontational approach to political issues, casting herself as approachable and quiet, yet deeply radical—an organizer and a storyteller all in one. This echoes Yau’s broader strategy of exercising her political views with vulnerability, driven by emotion and care.

Prose poems populate the second half of For now I am sitting here growing transparent, and the first, “Private Furniture Sonata,” retains a faint echo with the title: “The light in your home is never bright enough. You can’t make out anything transparent.” A few pages later, in the poem “To A Friend,” Yau pivots away from domesticity and instead focuses on intimacy, supporting a friend through shared jokes, references, and surprising notes of honesty that only ever arrive in the face of non-judgment. “I can’t believe we’re talking about this thousands of miles apart. In the same country but so far away.” As the creator of multiple spaces focused on sharing vulnerability around intimate experiences—such as the Sex Workers’ Film Festival and Women’s Theater Festival that she co-founded in Hong Kong—Yau argues that friendship is nothing without a sense of solidarity in the face of patriarchal bias.

Yau describes herself as simultaneously “the most overrated and underrated,” and this collection sees its poet eventually arriving at a kind of self-assured openness, a universe in which she can be both confessional and declamatory. Thus, For now I am sitting here growing transparent is not solely a detached work of art for art’s sake, but a radically prefigurative text intertwined with social movements and communities of care, creating a world without dichotomies between softness and strength.

mk zariel {it/its} is a transmasculine poet, theater artist, movement journalist, & insurrectionary anarchist. it is fueled by folk-punk, Emma Goldman, and existential dread. it can be found online at https://linktr.ee/mkzariel, creating conflictually queer-anarchic spaces, and being mildly feral in the great lakes region.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: