Humans throughout history have been fascinated by the elements. Unfathomable forces of nature, they entered our myths and minds aeons ago. There’s no time when we’re not in their thrall. Drawing from the vast store of our collective imagination across mythology, philosophy, religion, literature, science, and art, I present Elementalia, a series of five element-bending lyric essays that explores their enchanting stories and their relationship with the word—making, translating, and transforming meaning and message. This is not an exhaustive (nor exhausting) effort that covers every instance of and interaction with each element, but rather an idiosyncratic, intertextual, meditative work—a patchwork quilt of conversations with other writers, works, and texts across space and time.

Earth is cracking along her fault lines. And most of these fault lines are now human.

*

[William of Baskerville, a Franciscan friar-turned-detective:] “This is what we need: a way to get into the library at night, and a lamp. You get the lamp. Linger in the kitchen after dinner, and take one…”

[Adso of Melk, his protégé, a Benedictine novice:] “A theft?”

[William:] “A loan, in the name of the greater glory of the Lord.”

[Adso:] “If that is so, then count on me.”

– Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose

*

*

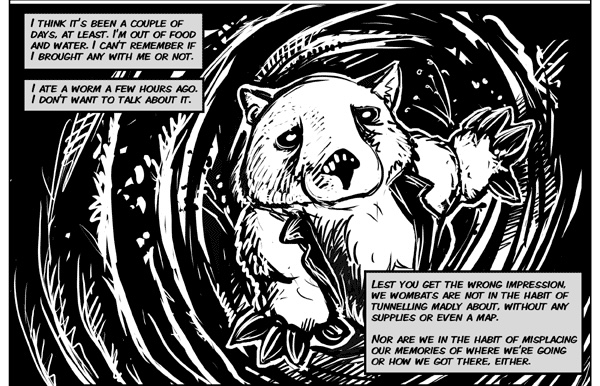

– Ursula Vernon, Digger

*

मुद्रा:

mudrāh

yogic gestures

*

THE ILLUMINATOR

The brown-robed monk sits at his desk by the darkening window. Aureoles shimmer on the beeswax candles that dot the scriptorium. He studies the folio of parchment, its frontispiece inlaid with gold leaf and held breath, burnished with a hound’s tooth. Verdigris, orpiment, vermilion. The nimbus of his hand seems to float over the letter. Ultramarine. He rubs at the pigment smudged on his thumbnail. He can no longer discern the vagaries of the vellum, nor the temperament of the scribe’s quill in the quire’s murky oakgall ink. He closes his eyes. The sum of all colours is an exaltation.

*

“Now Soma was in the heavens and the gods were here [on the earth]. The gods desired: ‘Would that Soma might come to us; we could sacrifice with him, if he came.’ They produced two apparitions, Suparṇī and Kadrū; Suparṇī in truth was Vāc (Speech) and Kadrū was this [Earth]. Disagreement broke out between them.

They then argued and said: ‘Whichever of us can see farthest will have the other in her power.’ ‘So be it.’” Roberto Calasso in Ardor.

I’ll have you know, before we proceed any further, that all the stories favour Suparṇī, also known as Vinatā, the modest one, mother of the golden eagle Garuḍa. (Nobody remembers that Suparṇī, in her impatience to see if her sons are indeed better than Kadrū’s, breaks the first of her two eggs and causes poor Aruṇa to emerge premature and malformed.) Kadrū asks for a thousand sons instead, and becomes the mother of a thousand serpents. Earth must be fruitful, after all. Their argument—one of many for they are sisters, both wives to the sage Kaśyapa—is about a horse in the distance and the colour of its tail.

“What Kadrū (Earth) sees and her sister Suparṇī (Speech) does not see—in the far distance beyond the ocean where that horse appears who is Agni—is the rope that ties the horse to the sacrificial post: ‘None other than the rope.’ Speech, in comparison with Earth, is she who does not see with total precision. And total precision is a rope that is tied to death. And so Kadrū challenges her sister to carry out the very action that can redeem her from death: the theft of soma [ambrosia]. It is as if Kadrū had said: Since you are like this—and you do not see what ties you to death—you have to fly off into the heavens and carry out that brave task which alone can redeem you from death. Otherwise, not seeing the rope that ties you to the sacrificial post means being already dead—or at least having lost your Self.”

What does Earth know that Word does not? Will self-righteous Word ever take a look at what much-maligned Earth is saying? Can Word learn?

Robert Macfarlane says in Landmarks:

“In Which a Baroque Fantasia Is Imagined

We need now, urgently, a Counter-Desecration Phrasebook that would comprehend the world – a glossary of enchantment for the whole earth, which would allow nature to talk back and would help us to listen. A work of words that would encourage responsible place-making, that would keep us from slipping off into abstract space, and keep us from all that would follow such a slip.”

*

“In a cedar-shake shack on a cliff–but we all live like this–is a man in his thirties who lives alone with a stone he is trying to teach to talk.

Wisecracks on this topic abound, as you might expect, but they are made as it were perfunctorily, and mostly by the young. For in fact, almost everyone here respects what Larry is doing, as do I […] Larry removes the cover for the stone’s lessons, or more accurately, I should say, for the ritual or rituals which they perform together several times a day.

I assume that like any other meaningful effort, the ritual involves sacrifice, the suppression of self-consciousness, and a certain precise tilt of the will, so that the will becomes transparent and hollow, a channel for the work.” Annie Dillard in Teaching a Stone to Talk.

*

HOW TO GROW A FOREST

from Hayao Miyazaki’s 1988 film My Neighbor Totoro

Little Mei and Satsuki have moved to a new town. Their mother Yasuko is in hospital undergoing treatment. They live with their father Tatsuo, a university professor, in a charming old “wreck” of a house by a great camphor tree at the edge of the forest. Mei has made the joyous acquaintance of Totoro, a mysterious kami, a guardian spirit of the forest. The Kusakabe family is slowly settling in.

One rainy evening, Satsuki and Mei are waiting at the deserted Tokyo Electric railway bus stop with an extra umbrella for their father. It’s getting dark and the rain isn’t letting up. Under the solitary street lamp, Satsuki is playing ayatori, cat’s cradle, a game of changing shapes. Rain falls in glinting lines parallel to the tall dark trees. Mei is falling asleep clutching her sister’s skirt, and is soon hoisted piggyback. Ripples spread in overlapping circles in puddles.

Footsteps. A large furry foot with five claws sloshes into view. Totoro! Enormous Totoro wearing a tiny leaf hat, raindrops falling on his nose plink plink. Satsuki lends him the spare umbrella. The first patter of raindrops on the umbrella trrtt makes his fur stand on end. He listens with growing thrill. Until he can’t bear it anymore and makes a thunderous bounce that lets loose a deluge upon their heads. He roars in delight. Catbus arrives beaming, wearing a matching grin. As he leaves, Totoro hands Mei a tiny parcel “wrapped in bamboo leaves and tied with dragon whiskers, full of magic nuts and seeds.”

The sisters plant the seeds in the garden. Mei squats all day with a watering can waiting for them to sprout.

Now the moon is full. Someone holding an umbrella is walking round and round the plot with two little companions. Oh, they’re jumping over the plot and back! Satsuki and Mei rush out from under their mosquito nets. They take their places. It’s time.

Hands together squeezing down, up and back stretching wide, squeezing down, stretching wide, squeezing down, stretching wide. Totoro grunts in effort, sweat beading on his fursome forehead. A sprout pops up from the earth pop. Satsuki powers through, brow furrowed, elbows out. Mei digs her toes in and tilts her head back extra. All pull together, and more sprouts go pop pop pop pop.

An invisible threshold has been crossed, and now they’re flowing in unison, and the plants are growing. Down to the earth, up to the sky. The plants are growing into trees. Down to the earth, up to the sky. Their trunks are growing taller and taller and thicker and thicker. Down to the earth, up to the sky. Their foliage is dwarfing the house where the girls’ father is working by lamplight, crowding the clouds out of the night sky. Down to the earth, up to the sky.

A forest has come to be. And it’s now time to fly.

*

भूमिस्पर्श मुद्रा

bhūmisparśa mudrā

the yogic gesture of touching the earth

Assume पद्मासन padmāsana, lotus. Place your left palm face up on your lap. Drape your right palm over your knee so that your fingers lightly brush the earth. You have now assumed the yogic gesture of touching the earth, a seal.

*

Night has fallen, and Siddhartha Gautama sits under the bodhi tree still. He has crossed every obstacle on the path. He is so close now. Only Māra, the great demon king of temptations, stands in his way. Gautama is deep in meditation, his hands folded in his lap in ध्यान मुद्रा dhyāna mudrā, his right palm over his left, both facing up. Gently he takes his right hand to his knee, extends his fingers to touch the earth. Earth, be my witness.

I’m unshakeable now, he seems to say, bring it on. That same night, he attains Buddhahood and establishes himself in supreme enlightenment.

“With your mindful breathing,

with your peaceful smile,

you sustain the mudra of Earth Touching.

There were times when you didn’t do well.

Sitting on earth, it was as if you were floating in the air,

you who used to wander in the cycle of birth and death,

drifting and sinking in the ocean of misperceptions.

But Earth is always patient

and one-hearted.

Earth is still waiting for you

because Earth has been waiting for you

during the last trillion lives.”

– Thich Nhat Hanh, Earth Touching

*

In classical Indian dance, a preliminary ritual has developed over time in which dancers ask for forgiveness from the earth—पादाघातं क्षमस्व मे pādāghātaṃ kṣamasva me—for striking her with their feet. Sitting, standing, walking, lying down are non-violent actions, and therefore, all right. But I still remember people from my grandparents’ generation touching the earth every morning—as they lowered their feet onto the ground from their beds.

Right hand and left hand; उपाय upāya, skilful means and प्रज्ञा prajñā, wisdom; संसार saṃsāra, temporal existence and निर्वाण nirvāṇa, transcendent liberation.

*

The Nine Nights of the Goddess, नवरात्रि navarātri. The tenth marks her day of victory. The goddess who is not outside my head vanquishes the demon who is not outside my head. This day also marks विद्यारम्भ vidyārambha, the beginning of learning, for little kids. But everyone joins in, kids of all ages, because we could all do with renewing our relationship with the written word year after year.

First I write on earth, and then on rice, and then in my notebook, the sacred syllables for Gaṇapati, elephantine maker and remover of obstacles, and Sarasvatī, goddess of the golden word. Invoking seed syllables, words, and gestures several thousand years old, I then make my offerings to her.

लं पृथिव्यात्मिकायै गन्धान् धारयामि ।

laṃ pṛthivyātmikāyai gandhān dhārayāmi ।

She of the essence of earth, to her I offer incense.

हं आकाशात्मिकायै पुष्पैः पूजयामि ।

haṃ ākāśātmikāyai puṣpaiḥ pūjayāmi ।

She of the essence of space, to her I offer flowers.

यं वाय्वात्मिकायै धूपं आघ्रापयामि ।

yaṃ vāyvātmikāyai dhūpaṃ āghrāpayāmi ।

She of the essence of air, to her I offer smoke.

रं अग्न्यात्मिकायै दीपं दर्शयामि ।

raṃ agnyātmikāyai dīpaṃ darśayāmi ।

She of the essence of fire, to her I offer the flame.

वं अमृतात्मिकायै अमृतमयाहारान् निवेदयामि ।

vaṃ amṛtātmikāyai amṛtamayāhārān nivedayāmi ।

She of the essence of water, to her I offer nectar.

सं सर्वात्मिकायै सर्वोपचारपूजां सङ्कल्पयामि नमः ॥

saṃ sarvātmikāyai sarvopacārapūjāṃ saṅkalpayāmi namaḥ ॥

She of the essence of all nature, to her I offer everything.

Earth as earth, holding below. Earth as space, holding above. Earth as air in between, inside and outside. Earth as fire for creation and destruction. Earth as water for nourishment and dissolution. Earth as everything. Earth to earth.

*

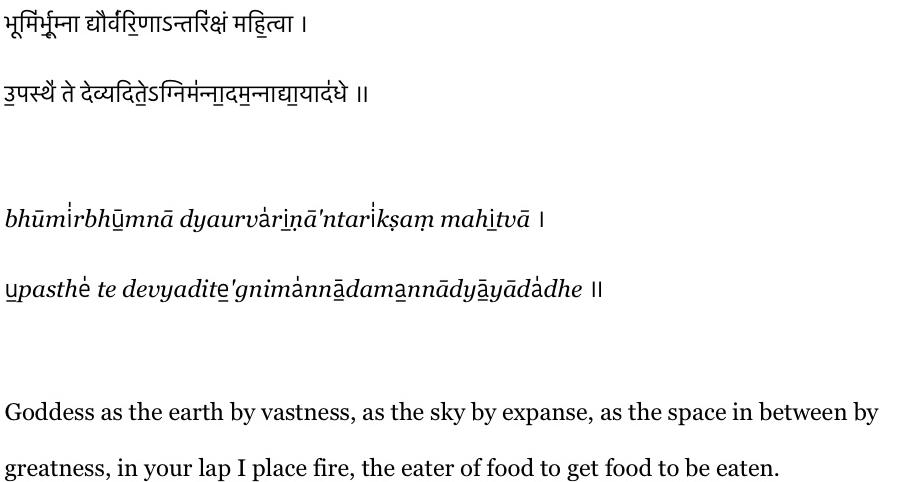

The Vedic Bhūsūkta, Hymn to Earth, starts thus:

“In traditional agriculture, the soil is the mother. She’s the mother who gives, to whom you must give back,” says scholar and activist Vandana Shiva. Here in India, when we work with the soil in the garden, we get real close to the earth. We squat in it, we get into it barehand and barefoot, we relocate earthworms and bugs by hand. With gloves and shoes on, how can you really feel anything? That would be like trying to eat—without the food touching the insides of your mouth. You can only protect yourself so much from the thing you want to get to know; you can only hold back so much.

In Gardens of Awakening, a book about Kyoto’s Zen gardens, Kazuaki Tanahashi and Joan Halifax Rōshi translate a poem attributed to Jianzhi Sengcan called Engraving Trust in the Heart:

“Missing the way by a hair’s breadth,

you separate earth from sky.

If you want to see the way as it is,

do not affirm or deny it.

Dividing things by opposites

is a disease of the mind.

[…]

Trust in the heart is not-two.

Not-two is trust in the heart.

Words, unspoken,

go beyond past, present, and future.”

In trying to understand the characteristics of authentic Zen art, these are the spoken ones Tanahashi arrives at: “direct (tanteki 端的), ordinary (buji 無事), vigorous (kappatsupatsu 活潑々), gleaming (jakushō 寂照), pivotal (daiyū 大用), nondual (funi 不二), and inexhaustible (mujinzō 無盡蔵).”

She of the essence of all nature, be my witness.

*

UNWRITTEN POSTCARD FROM WAYANAD

Dear V: If you were here, you would find yourself wrapped in a cold, white mist, and through the mist, you would see towering green dripping with water. You would rise before the sun and make your way among the birds, the frogs, and fallen mayfly wings to draw water from a blackened, steaming cauldron over the fire. Your glasses would fog up. Or you might go down to the river. I went with a bunch of kids. I stumbled a bit, donated blood to leeches, and almost missed a small viper about to fall on my head. They asked me Akka, what do you want to be when you grow up? Out of the mouths of babes. I’ve been having long talks with S, who has been at work for decades making this forest, carrying on W’s work after he died. We went up the tower with the kids and made animal sounds into the void. P’s rare orchids are in full bloom. Last afternoon, A and I, he’s in his late 80s now, sat by the field for some three hours waiting for the black cobra to reappear. It didn’t, so we went and made a dozen jars of orange marmalade. He taught me how to use the old wooden crank. Later, I made fresh coconut milk from scratch to put into my big pot of vegetable stew. I think everyone liked it because they emptied the pot.

*

“I thought the earth remembered me,

she took me back so tenderly,

arranging her dark skirts, her pockets

full of lichens and seeds.”

– Mary Oliver, Sleeping in the Forest

*

नमस्कार मुद्रा

namaskāra mudrā

the yogic gesture of offering respect

Assume पद्मासन padmāsana, lotus. Touch your palms to each other in front of your heart. You have now assumed the yogic gesture of offering respect, a seal.

*

*

കൃഷ്ണലീല-2

കുറേക്കാലം മുമ്പ് ഹരിയാനയിൽ ഒരു ഗ്രാമത്തിൽ ഒരു കുടുംബകലഹം വളർന്നു പെരുകി. വാഗ്വാദം മൂത്തു തെറിവിളിയായി. തെറിവിളി മൂത്തു തല്ലുകൂടാനായി അവർ ഒരു പാടത്തു കൂട്ടംചേർന്നു. ഇരുവശത്തും പത്തിരുപത്തിയഞ്ചുപേർ.

ഒരു സംഘത്തെ നയിച്ചിരുന്ന അർജ്ജുൻ പെട്ടെന്ന് മന:പ്രയാസമനുഭവിച്ചു തല്ലുകൂടാൻ വയ്യെന്ന് പറഞ്ഞു മാറിനിന്നു.

“ഒക്കെ ചാർച്ചക്കാരാണ്,” അർജ്ജുൻ പറഞ്ഞു. “എനിയ്ക്കു തല്ലാൻ വയ്യ.”

അപ്പുറത്തു ദുര്യോധൻ, കരൺ, എന്നിവർ കൂവിവിളിച്ചു, “ബേഞ്ചോദ്!”

അർജ്ജുന്റെ സുഹൃത്തും ചാർച്ചക്കാരനുമായിരുന്ന കിഷൻ എന്ന പാലുവില്പനക്കാരൻ അർജ്ജുനെ ഒരു വശത്തേയ്ക്ക് മാറ്റി കുറെ തെറി പറഞ്ഞു. (ഇന്നും യുദ്ധവിമുഖരായ പട്ടാളക്കാരെ അവരുടെ മേലുദ്യോഗസ്ഥന്മാർ തെറിവിളിയ്ക്കുന്ന ഒരു പാരമ്പര്യം സേനാവിഭാഗങ്ങളിലുണ്ടത്രെ.)

വീണ്ടും അർജ്ജുനെ പാടത്തു കൊണ്ട് നിർത്തിയിട്ടു, മറുപക്ഷത്തെ ചൂണ്ടിക്കാട്ടി കിഷൻ ഉച്ചത്തിൽ പറഞ്ഞു, “മാറോ, സ്സാലോൻ!”

അർജ്ജുൻ “സ്സാലേ, ബേഞ്ചോദ്!” എന്ന് പറഞ്ഞു തല്ലു തുടങ്ങി.

കിഷൻ പറഞ്ഞതും അർജ്ജുൻ പറഞ്ഞതുമൊക്കെ പാടിനീട്ടി അനുഷ്ടുപ്പിലാക്കി പ്രസിദ്ധപ്പെടുത്തി പ്രസാധകന്മാർ പിന്നീട് മുതലെടുത്തു.

ആരും സംസ്കൃതത്തിലായിരുന്നില്ല തെറിവിളിച്ചതെന്നും ഇവിടെ പറഞ്ഞുകൊള്ളട്ടെ.

KRISHNALILA–2

Sometime back in a village in Haryana, there was this family feud. Things got bad. There was a lot of name-calling. Itching for a fight, they assembled on a wheat field, a couple dozen guys on either side.

Arjun, the leader of the first faction, developed a sudden mental block and was all like, “I can’t do this, man. They’re all my relatives, you know.”

Duryodhan and Karan howled from the other side, “Benchod!”

Kishan, this milkman cousin of Arjun, drew him aside and swore at him. (High-ranking military officers have been known to swear at their battle-shy subordinates. It’s a thing.)

So Kishan led Arjun back to the field and pointed at the enemies, “Maaro saalon ko!”

Get the sisterfuckers. “Saale benchod!” Arjun was in.

Later they picked up what Kishan and Arjun said, expanded upon it, set it to meter, and made a ton of money, the publishers.

Let it be noted that none of the swearing was in Sanskrit.

– OV Vijayan, Krishnalila-2, translation my own

*

TIMEKEEPERS

I. The Elephant Stables

Manda, he’d said, upper lip curling,

low-born, ponderous and dull, slapping

flank with the back of his hand, unfit

for a king.

II. Of Men and Beasts

The war

of eighteen days,

like all other wars,

was too long

and too short.

III. After

Peeling back the dark husk of the night,

the sky fixed a red eye on this:

IV. The White Watch

The pārijāta is a small, white, many-petalled flower. It is different from other flowers in that its fall from the tree is not artless. It descends in a clockwise spin on its scented vermilion stalk. Balsam and flame.

But this is a dawn doubly white. Luminous spirals have long hushed into armour and cloth and flesh.

*

“I slept as never before, a stone on the river bed,

nothing between me and the white fire of the stars”

– Mary Oliver, Sleeping in the Forest

*

ज्ञान मुद्रा

jñāna mudrā

the yogic gesture of knowledge

Assume पद्मासन padmāsana, lotus. Place your palms face down on your knees. Fold your index fingers so that they touch the base of your thumbs. Straighten your other fingers. You have now assumed the yogic gesture of knowledge, a seal.

*

Philosopher Isaiah Berlin notes in The Hedgehog and the Fox: “There is a line among the fragments of the Greek poet Archilochus which says: ‘The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.’

For there exists a great chasm between those, on one side, who relate everything to a single central vision, one system, less or more coherent or articulate, in terms of which they understand, think and feel—a single, universal, organising principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance—and, on the other side, those who pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory, connected, if at all, only in some de facto way, for some psychological or physiological cause, related to no moral or aesthetic principle.”

Hedgehogs and foxes and something similar to what psychologist Howard Gruber calls “networks of enterprise,” a continual cross-pollination of bodies of knowledge.

Berlin continues: “These last lead lives, perform acts and entertain ideas that are centrifugal rather than centripetal; their thought is scattered or diffused, moving on many levels, seizing upon the essence of a vast variety of experiences and objects for what they are in themselves, without, consciously or unconsciously, seeking to fit them into, or exclude them from, any one unchanging, all-embracing, sometimes self-contradictory and incomplete, at times fanatical, unitary inner vision. The first kind of intellectual and artistic personality belongs to the hedgehogs, the second to the foxes.”

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the father of modern neuroscience, has this to say of such foxes, “To him who observes them from afar, it appears as though they are scattering and dissipating their energies, while in reality they are challenging and strengthening them.”

Networks of foxiness.

Robin Wall Kimmerer says in Braiding Sweetgrass: “I could hand you a braid of sweetgrass, as thick and shining as the plait that hung down my grandmother’s back. But it is not mine to give, nor yours to take. Wiingaashk belongs to herself. So I offer, in its place, a braid of stories meant to heal our relationship with the world. This braid is woven from three strands: indigenous ways of knowing, scientific knowledge, and the story of an Anishinabekwe scientist trying to bring them together in service to what matters most. It is an intertwining of science, spirit, and story—old stories and new ones that can be medicine for our broken relationship with earth, a pharmacopoeia of healing stories that allow us to imagine a different relationship, in which people and land are good medicine for each other.”

There are ways of knowing and there are ways of knowing. And in my own head, all walls are down. Braided tales of foxiness for a brittle blue marble.

“Those who dwell, as scientists or laymen, among the beauties and mysteries of the earth are never alone or weary of life. Whatever the vexations or concerns of their personal lives, their thoughts can find paths that lead to inner contentment and to renewed excitement in living. Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts.” Rachel Carson in The Sense of Wonder.

*

*

“‘The beginning of wisdom,’ according to a West African proverb, ‘is to get you a roof.’” Annie Dillard in The Writing Life.

The beginning of wisdom is to get you a roof. The sky might fall on your head. The weight of stars might just crush your skull while you sleep. You put a sheet between the air of yourself and all else there is, or you are not going to live very long.

On the other hand, as Mizuta Masahide, samurai-physician-poet student of Basho, says in the translation by Lucien Stryk and Takashi Ikemoto:

“Barn’s burnt down—

now

I can see the moon”

*

“Where can the need for concealment be expressed; the need to hide; the need for something precious to be lost, and then revealed?” asks architect and design theorist Christopher Alexander in A Pattern Language.

“We believe that there is a need in people to live with a secret place in their homes: a place that is used in special ways, and revealed only at very special moments.

To live in a home where there is such a place alters your experience. It invites you to put something precious there, to conceal, to let only some in on the secret and not others. It allows you to keep something that is precious in an entirely personal way, so that no one may ever find it, until the moment you say to your friend, ‘Now I am going to show you something special’—and tell the story behind it.”

Alexander shores up support for this idea from Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space. He quotes: “With the theme of drawers, chests, locks and wardrobes, we shall resume contact with the unfathomable store of daydreams of intimacy.” But Bachelard goes a lot further in Earth and Reveries of Repose.

“It is clear then that when we are able to give all things their right dream-weight – their right weight of dreams – dwelling oneirically means more than dwelling through memory. The oneiric house is a deeper theme than the house of our birth, for it corresponds to a need that comes from farther away.”

Architect and earthbuilder Didi Contractor says, “When I was a little girl, everytime I had a daydream I would design a house for me to live it in.”

Bachelard continues: “If the house of our birth lays such foundations in us, this is because it is in conformity with deeper – and more interior – unconscious inspirations than just the concern with protection, than the first warmth preserved and the first light protected. The house of memory, the house of our birth, is built over the crypt of the oneiric house. In the crypt is the root, attachment, depth, the plunging of dreams. We ‘lose’ ourselves there. It has infinity. We dream too of the crypt as of a desire, as of an image sometimes found in books. Instead of dreaming of what has been, we dream of what ought to have been, of what would have stabilized forever our innermost reveries.”

*

BUILDING

a brief architectural brief

“Raise high the roof beam, carpenters.

Like Ares comes the bridegroom,

taller far than a tall man.”

– Sappho

Give me

a circle, a halo, a circumscription,

a sphere of eleven dimensions,

a list of lists,

a key.

Give me

a thunderstorm poncho,

an endangered turtleshell,

a backpack no heavier than 12 kilos,

a cave.

Give me

a terrace of food,

a garden of songs,

a communal lovebowl,

a lab.

Give me

the bones of mammals,

their tendons and ligaments,

their shrinkwrap of fascia,

a ship.

Give me

a compendium of excruciating minutiae,

a harem of small kitchen appliances,

a nest of mynahglitter,

a web.

Give me

the unfittable fit,

the face of the mask,

the toomuch that I ask—

Give me

or go home.

*

“but my thoughts, and they floated light as moths

among the branches of the perfect trees.”

– Mary Oliver, Sleeping in the Forest

*

चिन्मुद्रा

cinmudrā

the yogic gesture of consciousness

Assume पद्मासन padmāsana, lotus. Place your palms face up on your knees. Fold your index fingers so that they touch the base of your thumbs. Straighten your other fingers. You have now assumed the yogic gesture of consciousness, a seal.

*

– Ursula Vernon, Digger

*

ĀDYĀKĀLĪ

My peristaltic grief

cannot contain your

colossal roiling churn,

this ancient reckoning,

this stormgathering heart

of this darkdancing nebula that

is not even

yet.

Your provisional troth, your

glut and parch, the comings

and goings of your universe — too

much for me, I’m telling you.

All I know is

this sun’s ecliptic, and this

brief palimpsest, this visceral

vivarium.

You break my heart, you

wicked wildwoman.

Evolutionary spandrel

I, seeking manumission

from your infernal machine, I

am done. Mother, I

am ready to begin.

*

A single day in the life of Brahmā, a single kalpa, aeon, is said to be one thousand mahāyugās or great ages. 4,320,000,000 years in human terms. At the dawn of each such day, each a new kalpa for us, a long-stemmed lotus blooms out of the navel of Viṣṇu, and out of the lotus emerges Brahmā. सृष्टि sṛṣṭi, creation. A new universe, the oneiric house from the dream of Viṣṇu. And when each night falls, the universe ends, and only potentiality remains. प्रलय pralaya, dissolution. And then again and again and again, the cosmic pulse continues infinitely. Everything repeats itself, cycles within cycles.

The aeon we are in now is the श्वेत वराह कल्प śveta varāha kalpa, The Kalpa of the White Boar. Hiranyaksha, the असुर asura king, kidnaps Earth goddess Bhūmi and imprisons her in the depths of the cosmic waters. Viṣṇu assumes the अवतार avatāra, (descended) incarnation, of Varāha, a colossal wild boar, dives into the deep waters, and emerges with Bhūmi nestled safe in his tusks. Earth is born from the waters; Earth is secreted in the waters; Earth is found in the waters. The boar’s grunting, growling, midnight-blue form with lotus eyes is made of यज्ञ yajña, sacrifice. And as the great boar emerges washed from the waters—Heinrich Zimmer notes in Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization—what he says to her is: Every time I carry you this way . . .

*

ĀDYĀKĀLĪ CONTINUES

You laugh

uvula clanging

in the black abyss of your throat

open

matted locks rip

great skull bursts

open

monstrous bloodfleshlotus

cornucopia of a thousand striations

open

seething screaming streaming sulci

open

sluicing boiling churning spinning

trembling rocking cracking breaking

smoking flaming burning melting

rolling flowing moving spreading

crawling swimming running flying

teeming sloughing molting roosting

breathing drinking hunting eating

spitting pissing shitting bleeding

rutting siring spawning rotting

merging throbbing pulsing rising

I fall like air

endless

through your noumenon

round and round and round

down and down and down

in and in and in fecund

humus of your

womb

*

“All night I heard the small kingdoms

breathing around me, the insects,

and the birds who do their work in the darkness.”

– Mary Oliver, Sleeping in the Forest

*

हृदय मुद्रा

hṛdaya mudrā

the yogic gesture of the heart

Assume पद्मासन padmāsana, lotus. Place your palms face up on your knees. Fold your index fingers so that they touch the base of your thumbs. Touch your middle and ring fingers to the tips of your thumbs. Straighten your little fingers. You have now assumed the yogic gesture of the heart, a seal.

*

“Myanmar earthquake released energy of 334 atomic bombs”

– The Times of India

“Myanmar earthquake: level of devastation ‘hasn’t been seen in over a century in Asia’, says Red Cross”

– The Guardian

“Myanmar’s military junta makes rare plea for help”

– CNN

*

I’ve finished college and been working for a bit. I’ve acquired the swagger of the newly-minted adult, a bit of money in my pocket, and a certain freedom with my time. I go bouldering and free climbing with a bunch of people in the rocky hills outside Bangalore. It’s nothing I’ve made any effort to study or train in systematically, but I like it. The other day I did my first chimney climb, where you start from the bottom of a narrow chasm with your back to one rock face, push your hands and feet against the other, and climb upwards. As the chasm widens funnel-like towards the top, the challenge is: thinking through your changing posture while stretching almost horizontal, while also maintaining the necessary tension in your body so you’re still moving upwards and not falling all the way back down. I make it out into the light.

Today I’ve found this other break in the earth and jumped in. I keep walking down. When the edge of the ground goes over my head, my friend who’s been teaching me calls out: Do you know what you’re walking in? It’s not another chimney. It’s an earthquake fissure.

There are many tremors in many places over the years. There’s sleeping through and holding things down and standing in doorways and running down stairs and checking the news and calling people and providing aid and raising funds and attending cremations. There’s missing the big one in Kathmandu by a day, bags packed and plane uncaught.

*

“You’ve got to stop thinking like an Airbender. There’s no different angle, no clever solution, trickety-trick that’s gonna move that rock. You’ve got to face it head on.”

– Master earthbender “Blind Bandit” Toph Beifong

teaching airbender Aang the fundamental ways of earth,

Avatar: The Last Airbender, S02E09 Bitter Work

*

It’s the fastest I’ve ever moved in my life, so fast it takes a few seconds for my brain to register that my body is no longer in the autorickshaw and is here instead, a hundred feet away, kneeling on this still-warm asphalt in the gritty dusk of Bombay, pulling this little boy out of this insanely deep pothole in the middle of this busy, busy road, vehicles streaming past us, drivers screaming in rage, a few more seconds to have the mother snatch the boy from my arms and run wordlessly to their lean-to in the slum by the road, the boy’s skull uncrushed and fine, his tiny body unswallowed and whole, and a few more hours to get home and step into the shower and see the many, many tyre tracks over the skirt of my ivory kurta that never wash off no matter how hard I scrub.

*

ARUNACHALA, THE RED MOUNTAIN

a vignette

[starting theme playing]

[birds chirping, bicycle bells ringing, temple music playing, filter coffee stretching]

This is the bustling temple town of Tiruvannamalai, in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Home to Arunachala, the sacred Red Mountain and the ashram of the late Ramana Maharshi. Ancient Tamil poems mention the great forests that these slopes once held. Several hundred years ago, you could still have seen them.

[leaves rustling, peacocks rattling]

Geologically, the Arunachala hill belongs to a chain of ancient granitic rock called the Eastern Ghats, much older than the bigger, wetter Western Ghats. It rises from the surrounding plains to a height of 860m. This was once a tropical dry deciduous forest. But years of logging and manmade fires have left a rocky hill covered in a single species of grass, and dotted with boulders and small patches of stunted trees.

Efforts are underway to rewild the mountain and restore its complex ecosystems. The people are exploring how to live sustainably and teaching their children. They’re growing food—rice, heritage millets, oilseeds, pulses, vegetables, different varieties of greens, button mushrooms, fruit—and medicinal plants. They’re setting fire breaks and building with earth. They’re replanting over a hundred indigenous species, 15,000 trees each monsoon. Owls, peacocks, parrots, pigeons, sparrows, snakes, bats, lizards, and several insects are coming back. Cows, monkeys, dogs, and crows never left. Once tigers and leopards roamed the mountain, but that might still be a long way away.

[temple music playing, people chattering, street vendors calling, dogs barking]

Tonight is Kartikai Dipam. Pilgrims are circumambulating the mountain. Ascetics and beggars are lining the streets. Street vendors are hawking their specialties under sodium vapour lamps. We can hear many overlapping languages in the throng—Tamil, Sinhalese, Malayalam, Kannada, Telugu, Hindi, and others.

[thunder rumbling, rain falling]

A full moon has risen. A great fire will now be lit in a cauldron atop the mountain.

[temple bells ringing, prayers rising, rain falling]

Everywhere on the planet, the landscape and the living world are at risk from the activities of humans. Our relentless consumption of resources without regard or replenishment has destroyed ecosystems, pushed several species over the brink into extinction, endangered the earth. But we still have a chance to put things right, recalibrate our presence on the planet, reestablish our true fellowship with nature.

[thunder rumbling, rain falling]

Someone asked Ramana: How should we treat others?

Ramana replied: There are no others.

Here, the green is starting to come back.

[ending theme playing]

*

Big questions need not be chased after; they will come. We cannot set out to write something that endures; if there is a grain of truth in what we write, it will. Salman Rushdie, knifed eye endarkened, looking like Odin himself now, says: “I always try not to overstate the power of literature. What writers can do—and what they are doing—is to try and articulate the incredible pain that many people are feeling right now and to bring that to the world’s attention. I think writers everywhere are doing that right now, and that’s probably the best we can do: articulate the nature of the problem.”

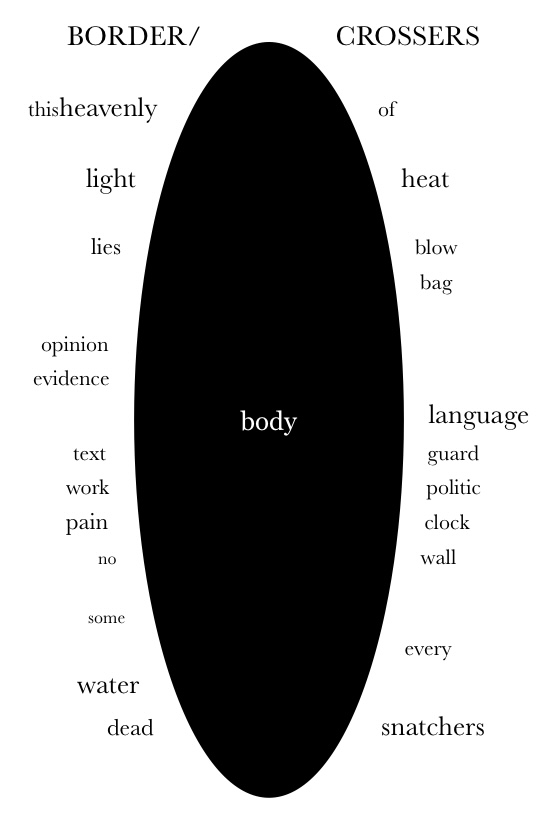

If we are part of the earth, there are no distant losses. All losses are personal. All poems are requiems. But we will lay out our medicine bundles. We will find. We will summon and name. We will mend and heal. And we will write, for as long as it takes. “Every language is an old-growth forest of the mind, a watershed of thought, an ecosystem of spiritual possibilities,” says anthropologist and ethnobotanist Wade Davis in The Wayfinders.

Chaotic-good William, lawful-good Adso, and the greater glory of something. A night, a library, a lamp.

*

“All night I rose and fell, as if in water,

grappling with a luminous doom. By morning

I had vanished at least a dozen times

into something better.”

– Mary Oliver, Sleeping in the Forest

*

“The final chapter is ours to write. We know what we need to do. What happens next is up to us.”

– David Attenborough

*

– Ursula Vernon, Digger

*

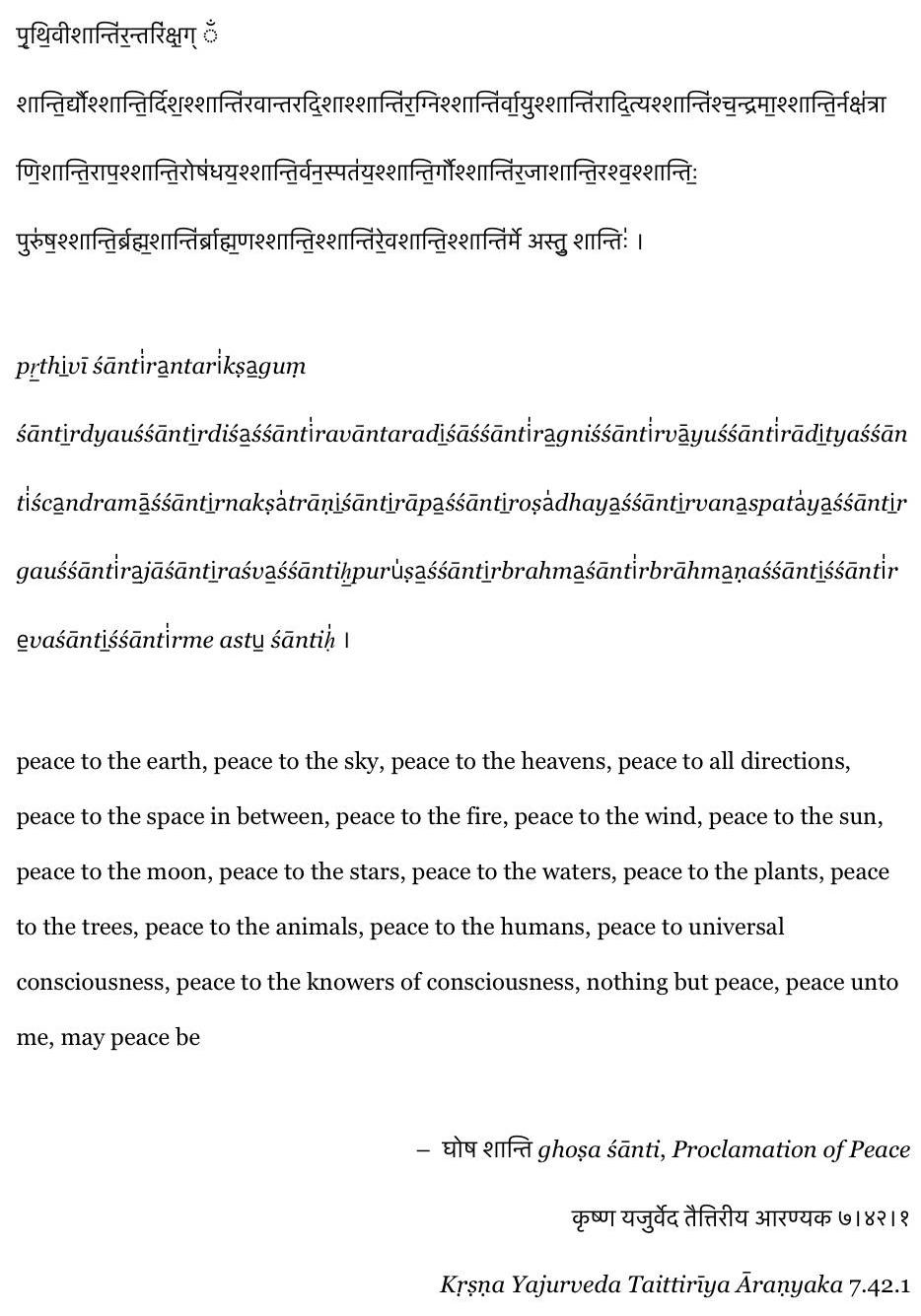

ॐ

सर्वेषां स्वस्तिर्भवतु ।

सर्वेषां शान्तिर्भवतु ।

सर्वेषां पूर्णं भवतु ।

सर्वेषां मङ्गलं भवतु ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

oṃ

sarveṣāṃ svastirbhavatu ।

sarveṣāṃ śāntirbhavatu ।

sarveṣāṃ pūrṇaṃ bhavatu ।

sarveṣāṃ maṅgalaṃ bhavatu ।

oṃ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ ॥

om

for all beings, may there be wellbeing

for all beings, may there be peace

for all beings, may there be fullness

for all beings, may there be auspiciousness

om peace peace peace

– शान्ति मन्त्र śānti mantra, Peace Mantra

***

Kanya Kanchana is a poet and philologist from India.

CREDITS

All © Kanya Kanchana, except where mentioned.

– Opening Image: Tiny bodhi leaves (Ficus religiosa) sprout from the roots of a big tree that had itself broken through concrete in its youth. Tamil Nadu, India.

– Closing Image: A message for peace found among random graffiti. Kerala, India.

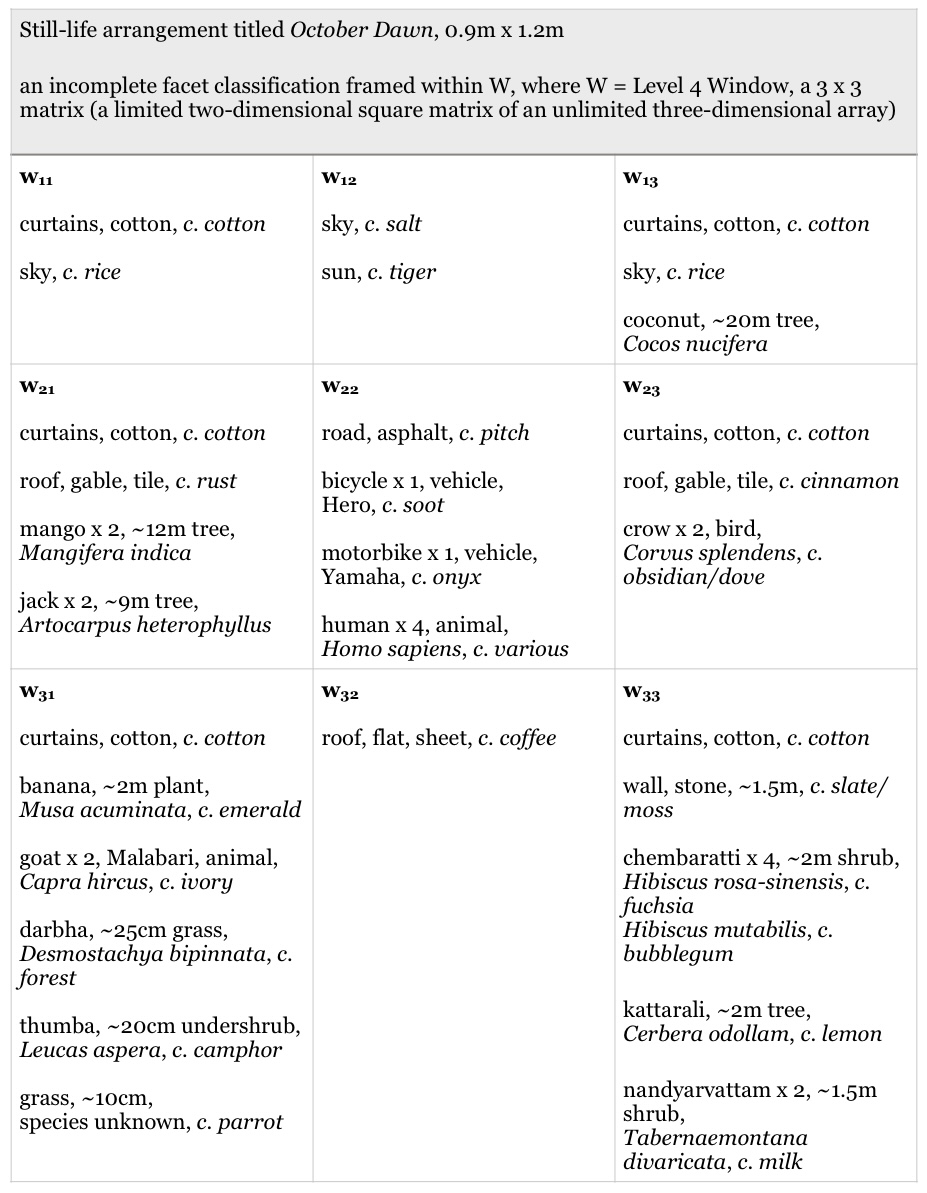

– The Illuminator, unpublished microfiction; border/crossers, unpublished poem; Timekeepers, poem first published in Mukoli; Still Life Arrangement, piece first published in Works & Days; Building, poem first published in The Common; Ādyākālī, Ādyākālī Continues, unpublished poems

– Krishnalila–2, microfiction by OV Vijayan, unpublished translation author’s own. Here Vijayan takes an enjoyable dig at the Bhagavad Gītā—at the whole seriousness of the enterprise—by transposing its prelude to contemporary rural Haryana in northern India and scaling the great war down to its essentials, the he-said-she-said of a family feud between cousins. I’ve retained the Hindi swear words from the Malayalam original.