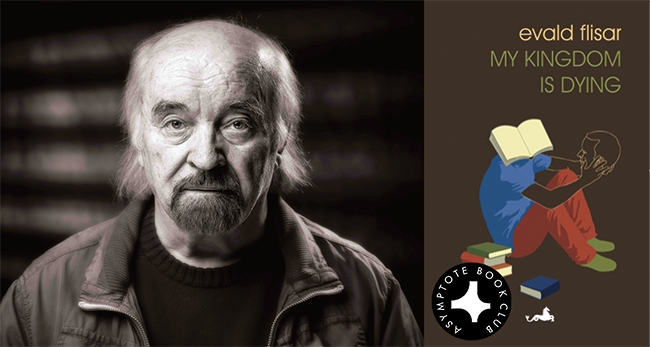

Having made his mark on nearly every literary genre from playwriting to children’s books, Slovenian author Evald Flisar has plenty to say about language and its multiplicity. So it is that a life lived in (and through) letters is at the centre of the wondrous and wandering My Kingdom Is Dying, the author’s latest novel to be translated into English, and our Book Club selection for the month of March. Following an aged writer in his recollections, Flisar constructs the barrier between memory and fiction as exceptionally porous in a mind prone to hyperbole, intertextuality, and philosophical ideals of narrative, making way for an astute investigation into the confabulation at the centre of our worldly regard. Here is the self as a living archive, as un-fact-checked autobiographies and indexes—as if each writer, each storyteller is a living incarnation of literature itself.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

My Kingdom is Dying by Evald Flisar, translated from the Slovene by David Limon, Istros Books, 2025

At the beginning of Evald Flisar’s latest novel, My Kingdom is Dying, a hypochondriac writer has just broken both his wrists in a bizarre fall, catalysing a decay of home and body that progresses with worrying speed. While convalescing, he lists all the maladies experienced throughout his long and distinguished career—thus far, he says he has

fallen ill three times with malaria (on one of these occasions with falciparum, which almost killed me), as well as typhoid fever, Legionnaire’s disease, pneumonia and Dengue fever . . . But then other things appeared: increased stomach acid (stress, said the doctor) . . . problems with my spine and vertebrae, I often had to spend a month immobile in bed . . . and then unexplained pains . . . my body was disintegrating. . .

He acquires a carer to aid him in the healing process, and with this, the reader is gradually drawn into a world wherein the two become increasingly physically and emotionally entwined. A literary tale about storytelling wouldn’t be complete without someone taking the role of Scheherazade, and with the arrival of the incredulous but devoted carer, the writer is given a perfect audience. As he narrates his own life, he is met by an enraptured, encouraging ear that is always wanting more.

The relentlessness of his self-obsession, iterated with stimulating humour, is continually exacted through his stories, and through their twists and turns, one eventually comes to understand and appreciate the literary goals of the real-life author: to compose a gentle satire about the process of writing literary fiction, and to shine a light into the odd situations authors occasionally find themselves in.

The first story the writer launches into is the (rather implausible) recounting of a sumptuous conference in India, the theme of which is the meaning of the short story. The conference takes place in a five-star hotel in Kolkata, where both famous and unknown delegates are helplessly throwing up quandaries about the nature and purpose of composition; there, the likes of John Berger and Susan Sontag are duelling unnamed international writers—including the narrator himself. As the telling progresses, Flisar includes subtle, anecdotal explorations in the art and nature of narrative, ranging from the Japanese author condemned to a closed circle of plagiarism—in which everything he writes turns out to have already been published—to the American who uses a mechanical plot-finder that “contains two thousand characters, events, circumstances and motives . . . from which it is possible to combine the highest number of possible stories following the principles of coincidence, polarity and similarity.” Meanwhile, the narrator’s literary ideals are perhaps the greatest out of all those in attendance—and the most obvious iteration of Filsar’s own philosophy—as he admits to an incredulous audience of literary counterparts:

It seems to me that the only progress would be a story whose effect, form and meaning would be total and universal, which would have all the available ingredients in the right proportions. A story that would be everything to everybody: a myth, a parable, literary discourse, a fairy tale, a legend, a psychological outline, a commentary on human fate, a philosophical puzzle; equally amenable to all, from a road mender to a mathematician, from a youngster to a literary ideologue.

At some point along the way, one becomes aware that the illustrious gathering at the Kolkata Hilton is entirely fictional. As events begin to repeat like glitches in the matrix—with writers attempting to escape but always being held back by external events—they finally end up in an all-consuming plague which traps all conference participants inside the hotel, while beyond, the numbers of victims continue rising.

Back in a slightly destabilised reality, the writer wraps up his telling of the Indian conference to delve into the story of his reunion with his own long-lost father. Here, one is given some insight into Flisar’s own native Slovenia, with idyllic countryside locations, childhood walks through the woods, and a village school where an astute teacher notices the extraordinary talents of a young would-be writer. There is also a kindly, wise grandfather, always ready to guide his precocious grandson, and of course—as we are now in the realm of the fairy-tale—the long-lost father is inevitably rich and well-connected, offering an escape from the rural to the urban, from eastern Europe to the cultural riches of London.

After moving through these nostalgic scenes of childhood and his early writing career, the writer suddenly pivots to describe what followed: a gradual onset of writer’s block, and the subsequent period of recovery at a Swiss clinic. Moving dramatically to an exclusive institution named after Hitler’s holiday home, the Berghof (a monicker generic enough to be coincidental until the trying nature of its treatments comes to light), he unexpectedly meets there the jury of the Booker Prize. Throughout the novel, Filsar continually imbibes the locations with literary significance and populates the pages with famed literati, using these elements to posit the enduring questioning of fiction’s function and its societal position. The notion of Martin Amis, J. M. Coetzee, Saul Bellow, and Graeme Greene all visiting the clinic on ‘Magic Mountain,’ with an unmentioned and unseen Thomas Mann eavesdropping on their conversations, is a particularly delicious affectation.

From autofiction to fairy-tale to thriller, one hardly has time to understand each narrative paradigm before the novel slides into another genre, culminating in a novel that strongly questions the nature, possibilities, and limitations of fictional writing. What remains consistent, however, is the demand put on the reader to ask themselves what is true and what is fiction; such concerns are articulated through the voice of the carer, to whom the narrative returns after each episode—a period of reflection and conversation between her and our writer. This is a book that presents art reflecting reality (or reality reflecting art) at its most potent and bizarre.

Flisar is one of Slovenia’s most notable literary exports, with a corpus including novels and plays that have been performed widely over many years, in languages and locations ranging from Tokyo to Reykjavík. His long and distinguished career began with a bursting onto the literary scene with The Sorcerer’s Apprentice in 1986, a novel since considered a classic in his homeland. What followed were thirteen novels, four travelogues, and over twenty plays. At the time of his induction into Slovene Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2023, his work had appeared in two hundred and fifty translations, making him the most translated living Slovenian author and playwright—but is Evald Flisar the most famous writer you have never heard of? If so, he is not unusual for that part of Europe once categorized as ‘the east,’ for although the walls came down some decades ago, it remains the lesser-known, lesser-referenced, and lesser-read part of the old continent. Often, the famous authors quoted in My Kingdom is Dying reminds one of the same imbalance: any reader would likely know Martin Amis or Saul Bellow, Salman Rushdie or Graham Greene—and yet the author-narrator himself remains anonymous.

We should be grateful that the art of translation has recently grown in appreciation, allowing many such long-neglected authors to gain new audiences. As Flisar demonstrates his finesse in fiction-writing through this spectacular and densely layered novel, David Limon offers us his own expertise in translation—with his deployment of understated UK idioms a particular delight in a translated world dominated by American English. A particular favourite is the deployment of lower register Anglo-English in a passage describing Percy Bysshe Shelley’s funeral: “there, his wife and friends, including Lord Byron, cremated his body using bunches of branches, and in a timely fashion one of his friends pulled out his heart from the flames, handing it to his widow.”

A master prosaist capable of luring the reader into the most psychologically complex of tales, Flisar’s books can seem at first simplistic and familiar, only to break out in unexpected ways. The late critic Eileen Battersby summed it up nicely in her review of his novel, My Father’s Dreams: ‘Flisar . . . has an individual approach to narrative. Logic does not interest him; human behaviour at the mercy of a damaged psyche is his chosen theme.’ Now, at the grand age of eighty, it seems that he has smoothed his edges and produced an all-encompassing work of fiction that dissects writing’s relationship to his own ‘damaged psyche.’ Indeed, My Kingdom is Dying is a quiet masterpiece of the type that his fictional persona constantly dreams about, and in reading, one cannot help but reflect on one’s own expectations of fiction: is it as entertainment or guidance, a show of cleverness or a revelatory potential? This thought plagues the narrator as well:

Maybe reality, too, is no more than a form of fiction. In a world where we demand evidence for everything, we are lost forever; in a world where reality, as we get entangled in the strands of analytical fiction, permanently evades us, what certainly remains present is only the endless possibility of love.

Michael Tate is the founder of Jantar Publishing, a London-based publisher of European Fiction and Poetry. He is a graduate of the University College London School of Slavonic and East European Studies, and has also studied at Univerzita Karlova in Prague.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: