Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico, translated from the Italian by Sophie Hughes, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2025

In the early 2010s, a specific gastronomic corner of the internet flourished alongside the rise of the Instagram aesthetic; food blogging evolved beyond sites run by home cooks from around the world, and social media brought its democratization to full swing. I too was among the converted. My weekends throughout grad school became increasingly spent wandering supermarket aisles in search of capers, plum sauce, sumac, fig jam, and macadamia nuts—which were especially hard to find in India at the time—while around me, artisanal coffee shops serving cold brews were just starting to appear, and the profession of pastry chef was becoming a lucrative pursuit. At the same time, a new generation of photographers emerged in Berlin’s culinary scene, sharing dreamy images of mid-century tables with pastel ceramic bowls of oatmeal and ruby-red berry coulis, positioned in wildflower fields with Photoshopped late-evening glow. Food, like everything else in life, became a highly publicized mode to exhibit the paragons of life, beauty, and self.

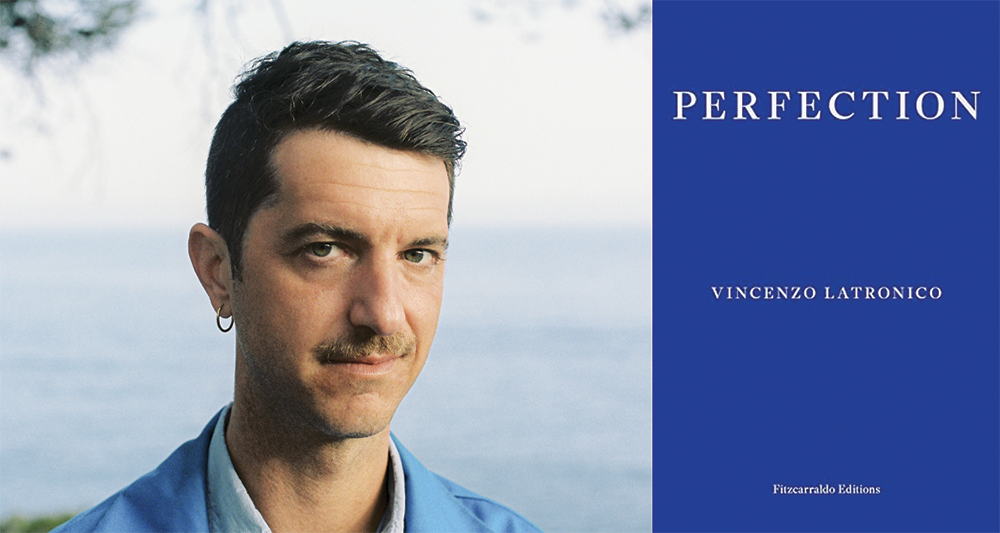

Vincenzo Latronico, a Milanese author originally from Rome, has previously written four books, but the Booker International-nominated Perfection is his first to be translated into English. Though the novel is affecting on several levels, it’s important to note that it will resonate differently with readers of various age groups. As a millennial, reading Perfection was like stepping into the looking glass; at times, it felt like the narrator’s striking delineation of the digitally idealized lifestyle, tinged with biting wit, was aimed directly at me.

The parasocial aspiration for the perfect image, the perfect avocado toast, the perfect holiday, and the perfect life form the core of Perfection, which begins with an objective reportage of a carefully curated apartment in one of Berlin’s increasingly gentrified neighbourhoods. The home is owned by two millennial expats, Anna and Tom, who are both digital nomads from some southern European country (perhaps Italy, though this is never specified), working in website design and marketing for global clients. The couple is often viewed as a pair, a dipole with vaguely sketched, amorphous identities, and in a third-person, “tell don’t show” approach, the narration allows us to clinically observe Anna and Tom’s lives over ten years, detailing on their living space, social interactions, jobs, tastes, and future aspirations in a changing Berlin. This almost anthropological study by Latronico strikes a solid balance between detached observation and wry humour, thriving under Sophie Hughes’s exemplary translation—which feels particularly significant as the lingua franca of English emphasizes that Anna and Tom could perhaps represent any person from this particular generation. Adding to this sense of universality is the lack of any dialogue or physical descriptions; just a few pages into the book, I realized that I didn’t know the colour of Anna’s hair—she could very well be me.

As acknowledged by the author himself, Latronico’s thematic tools draw from Georges Perec’s 1965 novel, Things: A Story of the Sixties, which explores the life of a Parisian couple, Jérôme and Sylvie. Perfection is anatomically resemblant to Perec’s Things, through the physical details set the two works firmly in their own times. Anna and Tom’s apartment boasts of monstera plants, New Yorker and Monocle editions, an ochre floor, petrol-blue upholstery, a Scandinavian armchair, spider plant cuttings in glass jars of water, an avocado seed just starting to sprout, and a limited-edition Radiohead album. On the other hand, Jérôme and Sylvie’s apartment has furniture “lacquered in dark red” with objects like “agates and stone eggs, snuffboxes, candy-boxes, and jade ashtrays.” Whereas the Berlin apartment has “monographs on Noorda and Warhol, Tufte’s series on infographics, the Taschen history of typefaces,” the Parisian flat features “a detail from The Triumph of Saint George, one of Piranesi’s dungeons, a portrait by Ingres.” Certain points of Perfection indicates that Latronico may have created a comparative illustration with Perec’s work—even Anna and Tom’s occupations possess some similarities with the market researcher couple in Things.

Perec’s story was based upon the bourgeois-bohemians of large French cities in the 1960s, where people had white-collar jobs, progressive politics, and increasingly defined tastes. His protagonists were part of the young brigade who sought a constant high standard of living, and the author uses their jobs in advertising as the central theme in his book, delineating how “the language of advertising is reflected in us,” and creating a position to criticize consumer capitalism. Perfection, then, goes one step ahead to capture the ethereal, non-material quality of social media in the twenty-first century. Latronico has spoken about how he was inspired by various Instagram photographs of monstera plants in living rooms during the pandemic, and his novel portraits this shiny world of objects—as well as the images and the fairytale stories associated with them.

Anna and Tom’s manicured surroundings aim towards a perfect picture, an ambition exacerbated by the fact that their digital life is intricately woven into their daily life. “Beauty and pleasure seem as inextricable from daily life as particles suspended in a liquid.” Having chosen Berlin in an attempt to create their own “mythology,” they take advantage of the city’s many offerings, attending gallery openings despite lacking genuine interest in art, constantly updating their Facebook and Instagram profiles, tagging locations of parties and bars, refueling on sushi. Eventually, however, the reader begins to notice tiny fractures in their impeccable façade, as a sense of omnipresent dissatisfaction looms over their apartment, jobs, meal plans, and social media presences, creating a gnawing exhaustion. The weight of possessions and the expectation to maintain an aesthetic architecture has entombed their authentic desires, and Latronico effectively captures this dichotomy through layered philosophical reflections:

That apartment and those objects weren’t merely reflections of their personalities: they provided a foothold, in their eyes proof of a grounded lifestyle, which, from another perspective (that of, say, their parents’ generation) appeared loose. In itself, chaos could be joyful, creative; but in that context, it only seemed to signal impermanence.

Even though the couple imbibes Berlin’s vibrant life, they are largely unaware of the broader European demography, the complex history of Germany, or the slow homogenization of the city—with English as the glue that holds their cosmopolitan community together. Their interactions with native Germans are limited, and their German-language skills are poor. This environment creates a quasi-monolingual existence, where everyone leans towards the “imprecise political left” and consumes news from similar liberal English sources, forming a “shared ideological koine.” Anna and Tom are one of the many keyboard activists tirelessly protesting and debating online about politics, class struggle, sex positivity, LGBTQA+ rights, or racism, contributing to a cyber ouroboros. However, such online polemics come to a turning point in 2015, when the civil war in Syria leads to a large-scale migration of refugees to Europe. In addressing this shift, Latronico writing proves deft and powerful, turning the earlier domestic bliss into a sharp sociological analysis. When faced with a real crisis, Anna and Tom realize that their skills don’t align with the urgent needs of their present situation; they organize efforts to catalog donated items, but such efforts at social work—along with the “meta-frenzy of this attempt to theorize their mobilization” online—proves to be ultimately misguided and fruitless. The irony of selecting a font for information pamphlets during such a grave situation was described with particular shrewdness; whenever Latronico mentions “Helvetica Neue Light,” the scene becomes increasingly amusing. Those of us who were caught in similar tumults will recognize the font as a symbol for a generation liberated by instant access to information, yet confined by hollow hipsterism.

Eventually, the protagonists try leaving freelancing for permanent jobs, but it doesn’t help. They move to Lisbon for a while, only to find the same emptiness they had felt in Berlin. Finally, they settle in the Sicilian countryside, where they live out days as if picking at old scabs. They are inevitably trapped in the world that we all helped create in the first place, a world struggling between endless images of a quasi-real abundance and limitless consumerism. We are in one way or another complicit in this cycle of dissatisfaction and material greed to achieve that perfect, abundant life. Can Anna and Tom escape? Can any of us?

In Things, Perec had written:

Sometimes it would seem to them that a whole life could be led harmoniously between these book-lined walls, amongst these objects so perfectly domesticated that they would have ended up believing these bright, soft, simple and beautiful things had only ever been made for their sole use. But they wouldn’t feel enslaved by them: on some days, they would go off on a chance adventure. No plan seemed impossible to them. They would not know rancour, or bitterness, or envy. For their means and their desires would always match in all ways. They would call this balance happiness and, with their freedom, with their wisdom and their culture, they would know how to retain and to reveal it in every moment of their living, together.

These lines could very well have been from Perfection. With its impersonal take on an entire generation, Latronico’s novel is indeed a deeply personal book of objects gazing back at us, full of questions about authenticity, reality, their significance, their future lives. Anna and Tom never truly feel fulfilled throughout the story; they are acutely aware that the life they present through their curated surroundings and their social media profiles is a veneer, and they understand that the fulfilment they derive from the likes and comments overshadows their actual experiences. Thus, the novel casts its eye out towards its readers, forcing an awareness of the time expended on digital avatars and the menial emotional returns this painstaking endeavour brings. It’s easy to criticize Anna and Tom when their efforts in social justice to find a more meaningful life seem small, but Perfection reminds us that we all play a part in the social and political changes caused by the internet—even if we don’t realize it.

Latronico succeeds in portraying a common existential ennui that flows from one generation to the next, changing its visage while retaining its emotional core—but he is also a millennial who understands our role in the digital world, and this novel is inherently rooted in that experience. Millennials are the first generation to experience the rise of the Internet while also growing up with older ways of communication and entertainment, and as such, we recognize the contradictions and vulnerabilities that come with a digital reality. Despite being swept up in the technological advances, we also remember a world without it, and this liminality is a perfect vehicle to explore the pros and cons of self-made identities. Perfection might have suited other generations or time periods, as seen in the case of Things, but it is ultimately the “iGeneration”—with the singular condition of being at once rootless yet globally connected, free and yet trapped—that gives this book its unique voice.

Sayani Sarkar has a PhD in biochemistry and structural biology from the University of Calcutta. She writes academic book reviews and interdisciplinary essays on her Substack newsletter called The Omnivore Scientist. Her reviews and essays fall within an intersection of science, nature, languages, arts, culture, and philosophy. Her works have been published in Full Stop, Tamarind Literary Magazine, LARB PubLab Magazine, Littera Magazine, The Coil Magazine, and The Curious Reader. Currently, she is the Editor-at-Large (India) with Asymptote Journal and a creative nonfiction reader for Hippocampus Magazine. She lives in Kolkata, India.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: