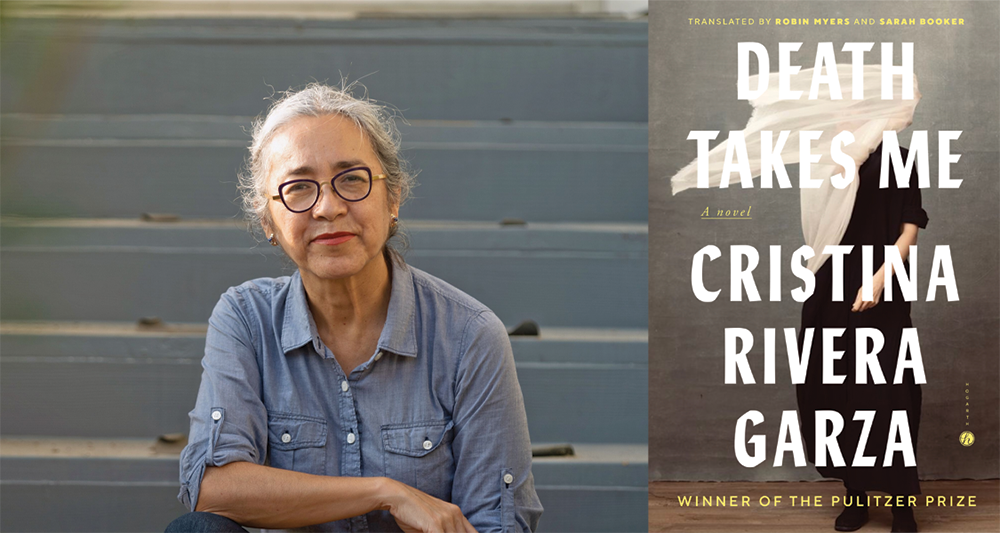

Death Takes Me by Cristina Rivera Garza, translated from the Spanish by Sarah Booker and Robin Myers, Hogarth, 2025

Death Takes Me, the latest novel by Cristina Rivera Garza to be translated into English, starts with a sort of epigraph titled “The Castrated Men.” The epigraph is a quote by Slovene philosopher and sociologist Renata Salecl: “However, with humans, castration should not be understood as the basis for denying the possibility of the sexual relationship, but as the prerequisite for any sexual relation at all. It can even be said that it is only because subjects are castrated that human relations as such can exist.”

The novel thus immediately establishes its premise, both in terms of tone and theme, but also hints at Rivera Garza’s fragmentary and intertextual writing style. By quoting Salecl, who was inspired by Lacanian theory on castration not as a physical mutilation but as a limitation on language, culture, and social norms, she throws the reader right into the middle of the type of discourse on gender dynamics with which Death Takes Me will attempt to engage.

As the novel begins in earnest, we find Professor Cristina Rivera Garza—the main character as well as the name of the author herself—on a run through the alleys of an unknown city when she comes across the body of a young man. The man has been mutilated, his penis cut off, laying in “a collection of impossible angles.” Accompanying the body are four lines of poetry, written in a red lipstick, from “Árbol De Diana” by Alejandra Pizarnik, a legendary Argentinian poet active in the 50s and 60s:

beware of me, my love

beware of the silent woman in the desert

of the traveler with an emptied glass

and of her shadow’s shadow

After reporting the crime to the police, Cristina, herself an expert in Pizarnik’s poetry, becomes entangled with The Detective, the woman assigned to investigate the case, both as an accomplice and a suspect.

More murders, all of men, all of whom have been castrated, and all involving Pizarnik’s poetry, unsettle the city as the novel progresses, and what follows is a genre-bending novel that intertwines elements of crime fiction, metafiction, and linguistic discourse. This is a premise in line with Rivera Garza’s larger oeuvre, which has been described as one full of “disturbing pleasure,” exploring gender violence, misogyny, and the limits of human language. While nodding to the classic structure of the detective novel, Death Takes Me inverts its gendered tropes: its two male characters, Valerio, The Detective’s assistant, and Cristina’s “Lover with the Luminous Smile,” are placed in roles typically assigned to the genre’s female characters. Instead of rational and scientific, they are portrayed as sensual and intuitive, and are never fully fleshed out. Post-coitus with an unspecified lover, Cristina wonders:

[W]hy isn’t he afraid? In the time that precedes pleasure and the time following it, the man hasn’t felt any fear. He’s in an unknown house, in an unknown bed, in an unknown body, and not for a second, not for even the tiniest sliver of that second, has he let himself be interrupted by fear. Or doubt. Or suspicion.

In its central crime, the novel offers an implicit nod to (and inversion of) the wave of feminicides in the city of Juárez. By modelling the narrator after herself, Rivera Garza is pointing a sharp finger to the literary and academic establishment for its role in perpetuating the linguistic and actual gendered violence in Mexico. But with the juxtaposition of the effort to solve this string of crimes and the text’s formal commitment to obscuring meaning, Death Takes Me raises the question: is it possible to write a novel that seeks to have a clear political message while also arguing against the desire to look for answers in literature?

First published in 2008 in its original Spanish, Death Takes Me, translated into English by Sarah Booker and Robin Myers, can be categorized as part of a larger wave of antagonistic literature—or antinovelas—seeking to disrupt expectations and create an uneasy relationship between the reader and the text, like Rachel Cusk’s Outline, which, though experimental in style, actively and constantly invites the reader to interpret the themes of the text and go beyond what is on the page. Death Takes Me, on the other hand, seems to categorically oppose the act of interpretation. Its many layers of reality, narration, and intertextuality conspire to hinder the reader from reaching any real conclusions. Interpretation is also explicitly likened to murder throughout the novel.

The crimes at the heart of the story—the dismemberment of the young men—problematize the physical and metaphysical realities of masculinity. Rivera Garza, as author and narrator, is intrigued by castration as a concept both in the literal and symbolic sense. The castration of these men is manifold: first and most obviously, they have had their genitals cut off. But the men have also been castrated in a more ontologically threatening way by being placed in the position of the female: la víctima, constantly revictimized through the reporting of their death. Rivera Garza frequently references the Chapman brothers’ sculpture Great Deeds Against the Dead, which depicts two castrated and dismembered men—the sculpture itself references Plate 39 from Goya’s The Disasters of War—and for Rivera Garza, it seems to serve as commentary on repeated spectatorship as repeated victimization. These men constantly suffer castration under the gaze of the reader. As the newspapers struggle with how to report on this unprecedented wave of androcide plaguing the city, we are faced with the stark fact that, in Spanish, the word for victim is always feminine. “No one, however, would find a suitable grammatical way to masculinize the victim,” Rivera Garza writes, “which was surely why—although it was surely for many other reasons, too—the newspaper would call it the case of the Castrated Men.”

This grammatical conundrum is, however, one that does not entirely translate into English, a language which doesn’t gender nouns like Spanish does. And with a focus on the theoretical framework of language and the episteme, the whole novel quickly becomes shrouded in a cloud of incomprehension. There’s a dizzying quality to the text; it is never quite clear, from one chapter to the other, or one sentence to the other, who is speaking, and the writing is choppy, jumbled—not-quite-stream-of-consciousness, not quite poetry. Cristina’s narration becomes increasingly unreliable as her personality begins to splinter and she takes on different personae. As a reader, we are made to question whether she could truly be the murderess: if she is capable of such gruesome acts. This sense of split personality drags the reader with it in a descent into madness. Anticipating her readers’ concerns and quoting Pizarnik, whose presence haunts the novel, Rivera Garza asks and answers, “Is clarity a virtue? I know no virtues. I only know desires.”

Similarly, reflecting on Pizarnik’s “journey towards prose,” Rivera Garza notes that Pizarnik was constantly “impeded by her own way of writing.” She quotes from Pizarnik’s diary:

My lack of rhythm when I write. Disjointed phrases. Impossibility of forming sentences, of conserving the traditional grammatical structure. I’m missing the subject. Then I’m missing the verb. What’s left is a mutilated predicate, tattered attributes I don’t know who or what to give them to. This is due to a lack of meaning in my internal elements. No. It’s more like a problem of attention. And, above all, a sort of castration of the ear: I cannot perceive the melody of a sentence.

This passage taunts the reader as Rivera Garza, the narrator, notes that Pizarnik’s issues can be summarized as 1) a lack of subject, and 2) a certain distance from reality, both of which also serve as a meta critique of the writing in Death Takes Me. It’s clear that Rivera Garza, the author, is aware of the impenetrable quality of her own writing. She’s doing it on purpose.

It is also clear that Rivera Garza wants the reader to let go of the impulse to interpret in order to soak in the feeling of the novel: obsession, madness, and violence. Towards the end of the novel, she muses on poetry and sets up an explicit opposition between the externality of prose and the internality of poetry (“THOSE WHO VERSIFY DON’T VERIFY”). Indeed, Rivera Garza seems to pose the very act of trying to bring clarity or meaning to a work of literature as an act of violence, likened to the decisive act of killing. Cristina receives a string of letters from someone first calling herself Joachima Abramövich, then later taking on the identity of real-life artists Gina Pane and Lynn Hershman Leeson—all of whom may or may not be the split personalities of the narrator herself and which act as conceptual and historical echoes of the novel’s project. The letter-writer insists: “Those who analyze, murder. I’m sure you knew that, Professor. Those who read carefully, dismember. We all kill.”

The Detective, in trying to uncover the truth of the murders and bring clarity to the case, is killing the poetic intention of the perpetrator (Cristina herself?) just as the reader is doing to the author by trying to find meaning. Rivera Garza quotes the philosopher Hélène Cixous, “All great texts are victims of the questions: Who is killing me? To whom am I giving myself over to be killed?” The act of interpretation is always also the death of the original meaning or the intention of the author, Rivera Garza seems to be saying.

Ultimately, however, the failure of The Detective to solve the case of the Castrated Men and catch the perpetrator comes to figure as a metaphor for and an indictment against society’s larger failure to re-imagine a world where women are not always the victims and where gender is not the governing structure of language.

Formally, then, Rivera Garza insists that interpretation kills art and she opposes the search for meaning in literature. Yet on the level of plot, the search for meaning is represented in the effort to solve the crimes at heart of the novel, and the failure to do so represents a political failure to come closer to understanding and solving the issues of misogyny. On one level, Rivera Garza celebrates the failure to find meaning; on the other, she condemns it. In the end, the overwhelming feeling that thus washes over the reader is one of confusion and disorientation. This takes the power away from the truly interesting questions she is trying to pose about gender, the place of poetry, and the (potentially violent) act of interpretation — questions she answers much more eloquently and efficiently in other work. As form and content fail to align, the novel suffers from the impossible task it has set itself, attempting to resist clarity while also delivering a clear political or linguistic message.

Linnea Gradin is a freelance writer from Sweden, currently based in South Korea. She holds an MPhil in the Sociology of Marginality and Exclusion from the University of Cambridge and has always been interested in matters of representation, particularly in literature. She has also studied Publishing Studies at Lund University and as a writer and the editor of Reedsy’s freelancer blog, she has worked together with some of the industry’s top professionals to organize insightful webinars and develop resources to make publishing more accessible. She writes about everything writing and publishing related, from how to become a proofreader or editor, and whether you need a translator certificate to be a good literary translator. Catch some of her book reviews here and here.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: