In the wartime world of Underground Barbie, our January Book Club selection, Croatian writer Maša Kolanović vivifies another realm that is both an escape and a radical interpretation of daily horrors: the playtime conjurings of children. With its many inventions playing out in the basements of houses and the corners of rooms, the scenarios of childhood imagination both mirror and refract the way conflict and nationalism intercept daily life, articulating a more intuitive, unfettered interpretation of ongoing events. The novel is translated with a deft attention to the prose’s texture and humor by Ena Selimović, and in this interview, both author and translator speak to us on working with this text and its singular voice, the transformation of pop objects across cultural divides, and how the language of play can speaks to its context.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Junyi Zhou (JZ): I’d like to start us off by asking you, Ena, about your history with Underground Barbie. How did you come across the book, and what drew you to translate it?

Ena Selimović (ES): The book and I share a ten-year history. Back when I was finishing my dissertation in comparative literature, a lot of the books that I was working from were not translated into English, so I found myself having to translate all these passages that were in my chapters. Underground Barbie, for me, was such a no-brainer because my dissertation was on the relationship between American and Balkan racialization—in other words, putting the perception of race in both places in dialogue with one another. In the Balkans people tend to think there is no such thing as race, but there very much is, and Underground Barbie really shows how race functions in times of war, because it depicts how children are remapping what it means to be pure Croatian.

Everything started there, and in 2019, Maša came to a conference in San Francisco, where I was then living. At that time I had written a plea for other translators to translate the book, but not thinking of myself as a potential translator at all. I didn’t think that was a career or something that I could pursue, because I’m not a native speaker of English. I also had the experience going back to Bosnia as a child and a teenager, and everyone would make fun of me for my American accent in Bosnian. It just felt like I couldn’t win.

But the more I thought about it, I realized that I had written both a chapter on this book and a plea for it being brought out in English—essentially, I’d read the book like ten times. Then, when I met Maša, I loved her, and we just clicked. She knows and respects my work, and she’s unusually humble, so one day I just asked her over coffee: “What do you think about me doing it?” She said yes.

JZ: It sounds like such a spontaneous process, and your collaboration together is really beautiful.

The narrator in Underground Barbie is a young woman, and the story is told from her point of view—though layered with a wisdom and incisiveness that comes with age. I find it interesting that while she’s making these really astute remarks, there’s still something innocent and unaffected about her. Could you speak more about your experience working with this dichotomy of tone? Was it challenging to maintain the balance between insight on one hand, and ingenuousness on the other?

ES: That was actually the biggest challenge, and it’s why the translation went through three complete drafts. Initially, my iteration was much more colloquial, diaristic, much more conversational in tone, with a much younger narrative voice. But the feedback I was getting from publishers is that it wasn’t literary enough, not incisive enough, or it didn’t do enough with language. So I thought, okay, how about upping the register, but keeping the spunk that Maša captures in her narrative?

There’s something about going through war that keeps the child in you alive. There’s the bad side of trauma and the good side of trauma, I think. The bad side would be that you’re stunted in a particular moment, but the good side is that you have the energy that’s captured from that moment, alive in you, forever. I don’t know if Maša wants to talk more about this. But I think we both very much have that child in us.

Maša Kolanović (MK): Yes, when war interrupts your play as a kid, you can never grow up. You always have this urge to reinvent your play so that you can go back to that point at which you were interrupted. In a way, the book is always coming back to the place of play. I think that this back and forth between the time of childhood and time of reflection, from a distant perspective, is what you said was your biggest challenge in translation, Ena.

JZ: Speaking of tone, I want to talk a little bit about humor. Underground Barbie contains many dark moments, for sure, but it is also quite funny. I’m thinking of the scene in which Svjetlana’s Ken is crippled by her young cousin, and the hilarity filtered through the narrator’s anger works especially well. What do you think of the role that humor plays in the novel? How did you factor it into your translation process?

MK: I can talk a little bit about the concept behind such scenes. The non-Mattel Ken doll in question was given the character of Dr. Kajfěs, a carnivalesque figure in the book. He is disgusting but at the same time also attractive to kids—the most subversive voice who is just tearing everything up all the time. He exists between the ideal world of Barbie—the pink world of imagination—and the real, darker world. When these two worlds collide, we are then stepping on these bombs of meaning and absurd connections. I’m glad to hear you found them humorous because I had lots of fun writing them, but I never knew if I was just laughing to myself, or how others would respond.

That said, I believe in the cognitive and emancipatory effect of humor, because it offers you the only exit from war and crazy, helpless, meaningless situations. It brings some kind of relief. And I also wanted my humor to be critical, to provoke a deeper level of thinking.

ES: The fact that the narrator has the agency to laugh about everything makes me cry harder. When teaching younger kids, the funniest ones usually worry me the most because I feel that their humor is also a defense mechanism for their realities. And sometimes the kid who laughs the hardest is in fact the most traumatized, which is not how we usually understand abuse or pain. I really like that Underground Barbie doesn’t give in too much to sentimentalism, because we have novels like Zlata Filipović’s Zlata’s Diary for that emotional tone. I’m not saying that the Diary is a lesser book—but it’s a different kind of book, and I think we as a society are primed for spunkier narratives. The narrator that we have in Underground Barbie is funny, strong, independent, and stands up to her brother when she can. It’s fresh to me.

JZ: I really appreciate your comments about catharsis in humor, and its inherent fragility that points us to its darker underside.

ES: Maybe I can relate the subject of humor to a larger context. Because the novel is set in Zagreb, everything is contaminated with war propaganda and paranoia. The language of propaganda, warfare, and paranoia eventually get to the kids and they can’t escape it; they can only rework it through their own language, and I think part of their reworking of language and politics lies at the center of this humorous effect.

JZ: I want to come back to Dr. Kajfěs. Arguably, he’s the pillar around which the children experiment with their gender roles and sexual curiosities as they’re playing in the basement. He occupies several violent vignettes, such as the duel between himself and another Ken, the body swap between himself and his Barbie bride, and so on. How do you see the connection between the children’s play of gender underground and the war overground? Do you think that their games can also be seen as a kind of war?

ES: I think that wars and nationalism are intimate, and they intrude naturally into your personal sphere, which includes your sexuality or gender. They work by way of bad poetry, and bad poetry is about objectifying the women and amplifying the men. The kids then play this out in the basement. In a sense, it’s how colonialism itself works on these very violently sexual or sexualized tropes.

MK: There’s so much power in in nationalism, and the kids are living in a relatively powerless world underground. But they also have power, and their power lies in their imagination, in their anarchistic impulses when playing, as Junyi put so nicely in her review; they have the complete freedom of how they want to play and what they want to do. Also, since the kids are in their tweens and facing the end of their childhood years, their sexual curiosities and the more decadent scenarios of play are appropriate to their stage in life. The world of grown-ups is so violent and boring, with nothing but news and politics, and they want to invent something else. They’re resisting this absurdist language and its violence. All of this explains how they play.

ES: I think this is where our reading of the book kind of differs. I don’t really see the children’s play as being completely free, because they aren’t immune to outside influences. I grew up in Turkey as a refugee during the war, and when I got lice and had to have my hair cut, my Barbie got a haircut too. But when my hair grew back and my Barbie’s hair never grew back, I realized I had done something awful to her. For me, the playing was a reflection of the reality that I, and the children, were immersed in.

MK: Of course, and I’m not contradicting you here. It’s an ongoing struggle, because the outside world is penetrating and infecting their play at the same time that the synopsis of real life is entering their games. They’re processing their experience through playing.

JZ: This is a great way to segue into imported popular culture in Underground Barbie, as it feeds into the reality that the children know and the imaginary world that they build. What case does the book make about how children receive and translate everyday information?

MK: Before the War of Independence, the culture in Yugoslavia was a mix between Western popular culture and Yugoslav popular culture. We had American soap operas, commercials, everything. And then there was a period of time when, as a kid, it was completely normal to watch reportage from some village or town where people were slaughtered. We were exposed to this brutal visual language of war. It was obscene, in this sense, to watch these scenes in tandem with the commercials of Western consumerism and abundance on the cable. The book tries to capture this obscenity.

ES: There weren’t any bounds at that time. Things weren’t rated. It’s kind of funny to imagine breaking news being rated.

MK: Yeah. I wanted to express this specific local situation of how we received popular cultural messages on the one hand, and how we responded to Barbie as a popular cultural icon on the other. Popular culture is a very vivid arena for meaning, and within the context of the war, the Western influence, and the image that Croatia built as being part of the West, children’s play is made even more complex.

ES: The popularity of these imported TV shows points to a kind of American semi-colonialism. The kids are literally playing with Empire, because they’re consuming all this proper “Western” stuff of empire.

JZ: Definitely. There’s an uncomfortable dissonance between the lived reality in 1990s Yugoslavia and the world that American media is depicting. And the children, in a way, are negotiating the tension between these two spheres.

I want to move on to the cacophony of voices and sounds in Underground Barbie. We hear news reports, radio programs, audiobooks, and songs. “And again—buzzing, banging, ringing, clanging, rustling, thundering, rumbling, howling, hear the language of my people!” What is the significance of sounds, whether they be speeches, radio signals, air raids, or music?

ES: Everything is so loud, right? And everything is an onslaught coming at you all at once. I think these sounds were really hard to translate, because they are so funny and so absurd in the original, so that’s why I ended up keeping the original words in there too sometimes, just for fun. But I’d rather pose this question to the readers, because it’s hard to know how one would respond to this challenge of having all these thick webs of sounds and references that they might not understand fully.

MK: I need to really give credit to Ena on her great translation, which was so difficult because she wanted to vivify all the violent and aggressive words and sounds. And the decision to transcribe them is very smart, because it’s good for the readers to hear the original language in its sounds and be aware of their specific effects. Another layer that I should mention is the omnipresence of the propaganda, the news, and the radio, which are always turned on in the novel. It points to the interconnectedness of the external world of grown-ups and the children, as they’re making their voice heard by creating their own news.

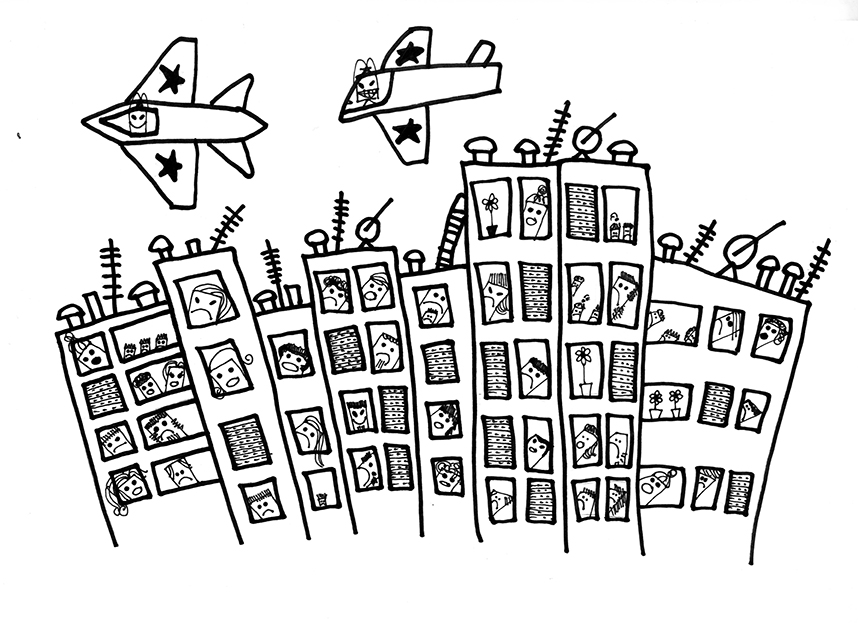

JZ: I love the whimsical drawings in Underground Barbie. Could you two talk a little about the relationship between text and image, and translation and illustration?

MK: Thank you so much. I love to draw, and I see my text in images. I think in metaphors, and I love how images enlarge the text, putting another layer of meanings and connotations. All my books of fiction are illustrated, and it’s something that I reward myself with after finishing a book—to think about the text in a more visual way. The illustrations in Underground Barbie are the most meaningful of all of my books, because they are organically attached to the texts. They’re simulating childish drawings and a playground for meaning.

ES: They’re much more playfully laid out in the original text, and have a bit more prominence in that they’re wrapped by the text. In that sense, they’re more in dialogue with the story.

JZ: This is more of a question for Ena. Did the illustrations impact your translation decisions?

ES: Only in hindsight. I grew more and more terrified knowing that publishers might not want to take on a book with illustration—but the illustrations were part of why I love the book so much, too, especially the one that starts off the book.

Image excerpted from Maša Kolanović’s Underground Barbie, courtesy of Sandorf Passage.

Maša Kolanović is a prize-winning author and professor best known for her genre-bending works of fiction and poetry. Her books include the poetry collection Pijavice za usamljene (Leeches for the Lonely, 2001), the novel Sloboština Barbie (Underground Barbie, 2008), the prose poem Jamerika (2013), and the short story collection Poštovani kukci i druge jezive price (Dear Pests and Other Creepy Stories, 2019). The latter received the 2020 EU Prize for Literature, the Pula Book Fair Audience Award, and the Vladimir Nazor Prize for Literature. She is an associate professor in the Department of Croatian Studies at the University of Zagreb.

Ena Selimović is a Yugoslav-born writer and co-founder of Turkoslavia, a translation collective and journal. Her work has appeared in the Periodical of the Modern Language Association, Words Without Borders, Los Angeles Review of Books, and World Literature Today, among others, and has received support from the American Literary Translators Association, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the National Endowment for the Arts. She holds a Ph.D. in comparative literature from Washington University in St. Louis.

Junyi Zhou is a writer and an Assistant Editor (Visual) at Asymptote. She received her BA from Vassar College and MPhil from the University of Cambridge, concentrating on English and film studies. Her published work can be found in Mediapolis.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: