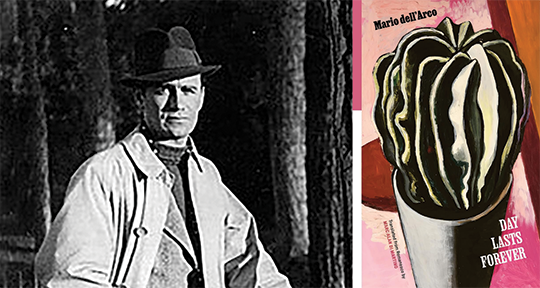

Day Lasts Forever: Selected Poems by Mario dell’Arco, translated from the Romanesco by Marc Alan Di Martino, World Poetry Books, 2024.

In his homeland of Italy, Mario dell’Arco’s stature rivals that of the greatest Romanesco poets: Giuseppe Gioachino Belli, Cesare Pascarella, Crescenzo Del Monte, Trilussa, Giggi Zanazzo. Despite this, he has long been ignored in the English-speaking world, but that is due to change with World Poetry’s recent release of Day Lasts Forever: Selected Poems, a healthy folio of work that spans the poet’s twenty-nine collections, starting with 1946’s Red Inside and ending with 1991’s Roma Romae. All translated by Marc Alan Di Martino (a talented poet whose most recent collection is Still Life with City), the poems are by turns lively, melancholic, curious, strange, beautiful, humorous, sardonic, and pithy, rendered in a way that moves the reader to savor them like a fine Genzano wine—or, if you prefer, “the whole green meadow” of a pistachio ice cream.

In 1905, Mario dell’Arco was born as Mario Fagiolo. Around age seven, he began writing poems in his native Roman dialect, and placed his first piece—a sonnet—in Nino Ilari’s L’Amico Cerasa when he was just a teenager. Later, as he became an architect and helped design such structures as the post office in Piazza Bologna and the Zodiac Fountain in Terni, he invented a pseudonym that would reference this vocation: “Archi-tect, arch, dell’Arco.”

In the introduction, Di Martino acknowledges that “the poems in this volume represent an entirely personal selection of [dell’Arco’s] work,” having chosen to focus on “the concise epigrammatic poems” in hopes of preserving the poet’s psychology and musicality. It is a vision that has been spectacularly fulfilled; he consistently manages to uphold the integrity of dell’Arco’s lines, giving due attention to the originals’ rhymes and balancing the various tones, rhetorical shifts, and punchlines, always leaving the reader with something mysterious and delightful to consider. Though Di Martino wonders if he has “over-represented certain themes (hunting, wine) at the cost of others (theology, nature),” the reader is unlikely to share this concern. Across the collection, many themes abound: the art of laziness, the nature of language, good architecture and the weather, the moon’s propaganda strategy, the heart of the scarecrow or the sunflower or the sundial, Jove and the deadly sins, the importance of life’s simple pleasures, self-isolation and the longing for reconnection, the absurdity of the artist’s life, watermelons and summer nostalgia, the history of Rome, light and darkness, a few unique felines. . . Is there hunting? Yes: some birds get shot. Is there wine? Plenty. However, those two elements do not distract from the coherency of the collection but instead enrich its whimsical personality.

Dell’arco’s poet-speaker can be quite mischievous and facetious, which adds to the collection’s charm. “How I Like It,” serves as a fine example:

I close the curtain tight so you can’t see.

Piece of cake, right? But it’s no joke.

You need a trained eye and a bit

of inspiration if you want to hit

your mark. And I’m a master at it.

So you live on the piano nobile, dressed

in your Sunday best, well-bred?

Left your Mercedes double-parked?

Too late. My spit lands on your head.

In the original, the end rhymes appear in the following order: “persiana,” “l’ingegno,” “d’estro,” “maestro,” “nobbile,” “festa,” “l’automobbile,” and “testa,” constituting a scheme of abbbcaca. Di Martino’s translation keeps the same flavor, though the first end-word does not pair with a perfect rhyme, and certain other couplings such as “joke” and “double-parked” are not so much half-rhymes as they are call-backs. However, none of this takes away from Di Martino’s accomplishment; the translator has prized good sense above all. The more obvious rhymes do enough heavy-lifting for the poem’s framework, giving Di Martino room to play around without losing the original’s veracity. Indeed, what the translator manages here is astonishing: he manifests the speaker’s strong, memorable, idiosyncratic voice—one that brings the reader to the poem’s side of things. Instead of feeling sorry for the person who has double-parked the Mercedes, we cannot help but laugh along in this timelessly comic scene, as who has not had the urge to commit petty revenge against a double-parker—especially a bourgeois one?

Dell’Arco is well aware that he is “a master” of literary comedy, and Di Martino, in sharing that awareness, must become the same to “hit [the] mark.” See dell’Arco’s “Propaganda”—

La Luna esce a lo scuro

cor lume a acetylene: sceje er muro,

butta uno sguardo intorno

e senza fa rumore

scrive cor gesso: «Abbasso er Capricorno,»

«Viva l’Orsa Maggiore. »

—and Di Martino’s iteration:

At night the moon sneaks into town,

flare in hand, picks a wall,

takes a look around,

and without a sound

writes: Down with Capricorn,

Long live Ursa Major.

Though the form is not identical, the slight difference in the lines’ length is justified by the verb “sneaks.” Di Martino’s first line “sneaks” across the page just as “the moon sneaks into town,” and from there, the reader is propelled into the surprising second line, which further personifies the moon, lighting up the page with a “flare.” The image, silly as it is, makes sense, and the personification does not prevent one from simultaneously imagining the literal moon lighting up a wall.

Although Di Martino’s wall of rhyme might not be as obvious and intricate as dell’Arco’s, the difference is unlikely to be distracting. Instead, the poem’s rebelliousness invites a relaxed reading, and by the end, one is likely to join the moon in its loyalty to the Great Bear, as well as its vehement opposition to the sea goat of Augustus and other rulers. “La Luna,” here, represents the poet’s will to revolt against the status quo, making “Propaganda” a kind of ars poetica à la Horace. No wonder dell’Arco rejected his traditional Romanesco sonnets in favor of these more groundbreaking, concise forms.

Some of Day Lasts Forever’s strongest poems are fables. Four works included from 1958’s Homage to Aesop illustrate the poet’s knack for reimagining myth and summarizing the Roman attitude toward life; “Diffidence” sketches “Jove’s one-thousandth birthday bash” in which the god rejects a gift from a snake, and “Jove’s Advice” consists of just two sentences of dialogue between the two. The snake complains that everyone keeps stepping on its head, but Jove instructs it to “‘Bite the first . . . the second will think twice.’” Then, following these archetypal characters, we find “The Collector of Fables,” an alluring bit of self-deprecation:

“Three-fifty for Aesop? Too much for me!”

the collector cries.

He finds dell’Arco. “How much for this?”

“Buy Aesop,” the bookseller replies,

“I’ll throw it in for free.”

In dell’Arco’s original, the rhymes follow an abcab scheme, but Di Martino deftly shifts the arrangement of the final two lines from ab to ba. This change, subtle and purposeful, illustrates Di Martino’s general approach to his translations; he allows just enough leeway to make the works his own, but always stays true to the poems’ basic organizational principles. Most importantly—he preserves the spirit of the poem, that which the great Swedish Nobelist Tomas Tranströmer once called the “invisible poem, written in a language behind the common languages.”

The final work included in this section—“Natura de li romani,” translated to “Roman Nature”—additionally highlights Di Martino’s virtuosic intuition:

“Go fill the Earth,” says Jove,

“with pride, anger, gluttony, sloth,

and every other sin. Now, move!”

And Mercury is off…

In Piazza Colonna, though, he trips,

spills his cargo. What’s done is done.

His voyage ends in Rome.

Throughout, dell’Arco has no problem poking fun at himself or his homeland, but as with the best comics, an edge of seriousness lurks under the poetry’s surface gloss. He uses comedy to display a deep understanding of not only Roman nature, but universal human nature. dell’Arco’s poet-speaker continually voices his own true inclinations—which may not always come across as flattering—but it endears him to the reader, as the Great Poet turns out to be, above all, a Human Poet, a Real Person who enjoys drinking trebbiano and malvasia, whose “. . . head is an impenetrable sky, / each thought a darkening cloud.” A man who sees himself as a cat with “. . . [s]cabs on [his] back, ransacked by fleas,” and a devoted lover who laments to his departed wife in a surprisingly long poem, “Solo”:

Dead, you’re frozen

forever. Ever more alone,

ever more lost,

every day I return

jarred by the chill and die

each day by your side.

In 2025, when fascism is once again on the rise in Italy and other Western countries, reading dell’Arco in Di Martino’s translation feels like a step toward a true freedom—one where “I’ve stumbled, by spiral’s end, / out of this world and into heaven”; where “the trill is in my heart”; where “[a]s long as you point your finger at the sun, / day lasts forever.” As such, this modest, rewarding selection from a vast corpus should be required reading for any serious student of translated poetry, and the architect-poet—honorably resolute in the dissemination of his Roman dialect—ought to be placed on the shelf next to Italian legends like Italo Calvino and Eugenio Montale. Where he may lack in popularity, he makes up for with pure gusto—and surely this aim is just as admirable as any other.

Jason Gordy Walker’s reviews and interviews have appeared or are forthcoming in Birmingham Poetry Review, Poetry Northwest, and others. A poet, prose writer, and translator, Walker has received support for his writing from the New York State Summer Writers Institute, Poetry by the Sea, the Newnan Artist in Residence Program, and other institutions. He holds an MFA in Poetry from the University of Florida.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: