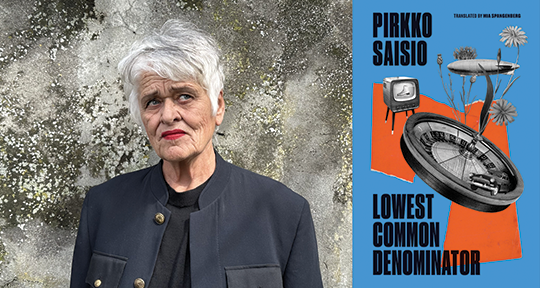

Lowest Common Denominator by Pirkko Saisio, translated from the Finnish by Mia Spangenberg, Two Lines Press, 2024

When Pirkko Saisio’s father passed away near the end of the millennium, she decided to write a book that explored her history; what resulted was an autofiction that follows the only daughter of communist parents as she comes of age in 1950s Finland. First published as Pienin yhteinen jaettava in 1998, it is now out in a superb English translation by Mia Spangenberg as Lowest Common Denominator. The first of three thinly veiled autobiographical novels, it is preceded in the Anglosphere by The Red Book of Farewells, and the third, Backlight, will soon follow. It is hard to believe that someone who is so critically acclaimed in her native language—with a writing career spanning five decades—is being translated into English only recently. The hope is that this is just the beginning.

With the death of Saisio’s father at its root, Lowest Common Denominator focuses on our narrator’s childhood and is essentially plotless, with vignette-like chapters arranged in achronological order. The majority of the chapters take place in the past, while the few sections set in the present follow the narrator in the days leading up to her father’s demise, as well as the aftermath. Most of the former are on the shorter side, focusing on a particular incident, event, or person, while the longer chapters explore a certain aspect or individual over an extended period of time. These usually take the form of character studies or personal histories of extended and far-flung family members. Throughout, Saisio’s prose remains straightforward though formally fluid, capably mirroring the narrative’s varied directions.

In her youth, the narrator had lived in Helsinki with her parents, who are members of the Finland-Soviet Union Society. They are not particularly well-off to begin with; her grandparents’ generation had been quite impoverished, and over the years, her father works various jobs while her mother helps out at a convenience store. Eventually, however, they obtain a small shop of their own and steadily become financially comfortable. Every summer, the narrator is carted off to her grandparents, who love having her around to stave off their own loneliness, and she too loves them despite their peculiarities.

Amidst these changes and vacillations, what endures is the narrator’s desire to be seen and recognised, to be acknowledged. While the adults in her life indulge in her whims and fancies, they don’t pay any serious attention. As she discovers that different people need her to sincerely adhere to their image of herself, she wishes there could be many co-existing versions of her so that everyone would be satisfied, while she can be who she wants to be. This is a recurring phenomenon. Later on, when she is old enough to join preschool, her experiences in class flow into the growing feeling of drifting away from the familiar, leading to new ponderances about the contesting demands and desires of the people in her life:

Be present (for Grandpa). Be quiet (for Father).

Be invisible. Be quiet. Be present.

Be comforting (for Grandma).

Be energetic. Be beautiful. Be a tomboy (for Aunt Ulla).

Be energetic, quiet, present, and good company.

Be beautiful.

Be comforting. Be a tomboy.

Exist (for Mother).

Voice is the most significant way in which Saisio showcases the character’s fragmentation. In the very first chapter, the eight-year-old narrator views herself in the third person while thinking up reasons for not going to school, creating and modifying a string of sentences in her head until she comes to the perfect sequence. She realises soon after that a breakage has taken place, a splitting to which her parents are not privy: “I had become she, the one always under observation.” This seemingly innocuous reflection is ultimately the idea on which the entire book is hinged: a startling self-definition which recognises and declares the self as separate, and selfhood as a mediated process of accretion. Often enough, the voice smoothly shifts between an intimate ‘I’ to an impersonal ‘she’ from one paragraph to the next, a deliberate move meant to underscore narratorial distance.

The idea of constantly being under observation holds even more weight in the context of a little girl waking up to the demands of gender norms and the ways in which they get policed by society. From a young age, the narrator had been largely disinterested in her girl-ness. She repeatedly rejected it: “I would like to be a boy. . . I’m going to be a father when I grow up.” Later, when she is pondering on how everyone wants her to emulate different contesting values, she wants a version just for herself: “And one who’s a boy, and that’s me. He spits and goes wherever he wants and doesn’t care about anybody or anything.” As she comes of age, the chasms between her and her parents—especially her mother, who begins to feel like a stranger—widen; she is unable to model the vision of womanhood her mother effortlessly projected, knowing that it will not be the same for her. “[S]he’s jealous of her mother and her dreamy contentment, the casual femininity from which she knows she will forever be excluded.”

Apart from the discomfort of gender, the narrator also becomes cognisant of her sexual identity—another aspect of herself that pulls her away and demarcates her as different. Her queerness strikes her for the first time when she witnesses the charismatic announcer at a revue held in a Helsinki amusement park: “And suddenly she realises what love is. She loves Miss Lunova. . . She loves Miss Lunova with a passion that consumes her, and she doesn’t have time to be scared or hope for anything until the final curtain is lowered.” She is so taken by her that she insists to her parents that Miss Lunova will be moving in with them, and becomes heartbroken when she realises that won’t be the case. Later on, when actual girlfriends and women lovers pass through her life, there is no mention of homophobia or rejection from her family—but it nevertheless remains for her an isolating experience.

As a result, the gap between how the narrator sees herself versus how she feels she is perceived grows stark. The particular experience of splitting is something that she brings up time and again in the childhood chapters: “[S]he’s been split in two. It’s a familiar feeling—it’s happened to her before. In fact, she’s been split into many selves: into one who’s invisible and one who’s present; into one who comforts and one who needs comforting; into one who’s a girl and one who’s a boy; into one who obeys and one who rebels.” In many cases, it is also a dissociative strategy that she uses to lessen the emotional and psychological impact of certain events. When the adult narrator finds her father seriously ill after a visit, the prose mirrors the startling and tragic nature of the discovery, yet Saisio’s use of negative space exacerbates the psychic distance she initiates to protect herself:

I rang Father’s doorbell. (Twenty-nine years ago it had been my doorbell, too.)

Silence on the other side.

I rang the doorbell again.

Then I peeked through the mail slot, but the inner door was closed.

I lit a match to illuminate the threshold.

His newspapers lay there untouched.

The light went out in the stairwell.

Andshe stands in the darkness, wishing she could fall into the soundless ellipsis of time and find herself somewhere else, far away from this dark stairwell.

But insteadI switched on the light again and tried to focus.

I need to hurry, I tried thinking.

I rang the neighbor’s doorbell—somehow I managed.

No one came to the door.

I rang the doorbells on Father’s floor—somehow I managed to ring them all.

No one came to their doors, and thenshe finds herself in the elevator.

Getting a child narrator right is no easy task, and Saisio executes it perfectly by painting the girl as a magnetic mix of precocious maturity and naive innocence, holding the potential for some surprisingly deep insights as well as silly hijinks. Humour, especially when a consequence of the mismatch between the narrator’s rich inner worlds and her ability to cogently communicate it to her loved ones, is a significant feature of the narrative, adding refreshing levity in between the heavy emotional punches. Still, it is ultimately a stirring pathos that threads the text, most notably when Saisio ponders the inexorable march of time. People grow old and die, places disappear, and you are no longer who you used to be—this feeling only increases as the narrator moves from childhood to adulthood: “Time no longer stands still. It gallops ahead like the black clouds now releasing their first heavy drops of rain.” Tomorrow comes and comes.

Areeb Ahmad (he/they) is a Delhi-based writer, critic, and translator who loves to champion indie presses and experimental books. He has served as an Editor-at-Large for India at Asymptote and as a Books Editor at Inklette Magazine. Their writing and translations have appeared in Gulmohur Quarterly, Sontag Mag, trampset, The Bombay Literary Magazine, The Hooghly Review, MAYDAY, and elsewhere. Their reviews and essays have been published in Scroll.in, Business Standard, Hindustan Times, Full Stop, Strange Horizons, The Caravan, and elsewhere. He is @bankrupt_bookworm on Instagram and @Broke_Bookworm on Twitter/X.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: