In regards to each translator’s unique and inimitable performance of their craft, Chenxin Jiang and Steve Bradbury here take their own stab at translating the poems of Yau Ching, followed by a translation and interview in which they discuss their methodology, the particular challenges of the Chinese language, and the purpose of having multiple translations of a single work.

The work of Hong Kong writer and filmmaker Yau Ching ranges across mediums of cinema, criticism, and poetry to address themes of gender, sexuality, and colonialism, building a corpus that is as philosophically engaging as it is intimate and emotionally prismatic. In the five poems published as part of our Fall 2015 issue, Yau displays her capacity for creating surprising images with powerful social and personal resonances, bringing in prevalent crises of contemporary consciousness and political instability while suffusing the lines with a confessional edge: “I am my mom’s / exemplar of a beautiful life / this fills me with suspicion of myself and the world / that represents me.” A full bilingual collection of Yau’s poems, For now I am sitting here growing transparent, is forthcoming from Zephyr Press in the US and Balestier in the UK, translated with a particular instinct for playfulness and musicality by Chenxin Jiang. Here, Jiang and fellow translator Steve Bradbury—whom Jiang credits for introducing her to Yau’s writing—take their own distinct approaches at translating the poem “時空,” and in the interview that follows, they discuss the craft of working with poetry, as well as their differences and admirations for one another’s work. It’s curious to see the variance in the resulting translations, as well as the meanings that can be derived from their interstices and collisions, giving new insight to the hermeneutics of reading and the technicalities of language.

時空

時間如影在路

英文的思念叫長

我長—長——的想妳

垂下兩隻袖兩隻褲腳伸長手指腳指伸長

每一條頭髮與眉毛

拖在地上如根

一隻黑鳥飛過

細細的影子在樹

葉子散落一地中文的寂寞叫空

一張白白的稿紙

「喂,再來情詩三首!」

半透明沒一個影子

世界很大而我短短的

坐在這裏 愈坐愈透明

沒有文字可填滿

我四面八方的空

與前前後後的長Timespace

Translated by Steve Bradbury

Time is like a shadow along a road

The English word longing is called long

To long, I long, for you

My sleeves, pantlegs, fingers and toes lengthen

Each hair on my head and brow

Trails along the ground like mangrove roots

A black bird flits by

Thin shadows across the trees

Leaves littering the groundLoneliness in Chinese can be called kong

Empty, hollow, void, a blank

Sheet of very white writing paper

“Three more poems and make it snappy!”

A translucency that casts no shadow

The world is so large yet I am so short and brief

The more I sit here the more translucent I become

Without a word to fill the plenitude

Of kong all the compass round

Stretching before and afterSpacetime

Translated by Chenxin Jiang

Time is like a shadow cast on the road

The English word longing has length in it

I long—long——for you

My sleeves pant legs lengthen fingers and toes lengthen

every single hair on my head and brow

stretches downwards trailing on the ground like banyan roots

a black bird flies by

casting its slender shadow on the tree

Leaves scatterLoneliness in Chinese is empty

An empty sheet of lined paper

“Hey you, three more love poems!”

translucent it has no shadow

the world is big and for now I am

sitting here growing transparent

No words can fill up

how empty I am on all sides

and, in front and behind, how long

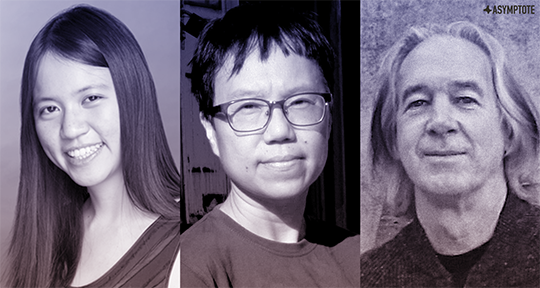

Xiao Yue Shan: Tell us a bit about how you feel about one another’s translations!

Chenxin Jiang (JCX): I wouldn’t be translating Yau Ching if it weren’t for Steve Bradbury, whose luminous translation of “Après Genet” first introduced me to her poems when we translated them together for Asymptote years ago. So it’s with some trepidation that I come to this duel of translations. Steve has also been a wonderfully generous interlocutor on all my translations of Yau Ching, so the translation presented here as mine already owes much to him.

Right off the bat, I loved the music of Steve’s translation. In line 3, he conveys the length of the word “long” with two iambic feet: “To long, I long.” And the flitting rather than mere flying of his black bird is delightful. My bird casts a slender shadow while his translation leaves it more ambiguous: “Thin shadows across the trees / Leaves littering the ground.”

I remember discussing with Steve whether to put the Romanization of 空 into the poem (if so, I think I’d still go for hung1 in Jyutping for Yau Ching’s Cantonese). Steve is right that “writing paper” is a little more accurate for the square-printed and not precisely “lined” writing paper familiar to all Hong Kong children. And who can resist an echo of Frost or Eliot?

Steve Bradbury (SB): When Chenxin first asked me to give her feedback on her translation of this poem (and then, to my chagrin, to make a version of my own), under the utterly misguided assumption that I was some sort of Yau Ching expert, I had several niggling concerns and quite a few suggestions, which looking back on now leave me thinking, “What on Earth was I thinking?” (But isn’t that the way it always is in this messy business called translation?) For one thing, I quite hated the fact that she had translated this poem before me and locked out so many great lines and phrases, just like the well-mannered, much-hated first-born who has managed to monopolize the label “good,” leaving the poor child that follows with no other choice to establish a distinct identity than to embrace the label “naughty.”

I actually like Chenxin’s version more than my own, it’s so clean, concise, and close to the source, but then I can read the Chinese—I’ve read it many times—and can thus fill in the blanks, so to speak, whereas my version is a little puffy with interlinear explication I felt compelled to add not only for the benefit of those who are unfamiliar with the Chinese language and culture, but, more importantly, to distinguish my version from Chenxin’s. I particularly love the alliteration and enjambment in her “trailing on the ground like/ banyan roots/ a black bird flies by/ casting its slender shadow on the/ tree /Leaves scatter”. Frankly, if I had been first to translate this poem, I am not quite sure I would have come up with lines that good even with the aid of ChatGPT4 or my much-loved but terribly battered “go-to-guy,” a 1978 paperback edition of Roget’s College Thesaurus. Chenxin’s closing lines are equally spot-on and cut-to-the-bone: “No words can fill up/ how empty I am on all sides/ and, in front and behind, how long” . .

And yet, having said that, I can’t help wondering if the closure of this poem might not be a paraphrase of, or at least an allusion to, lines in Robert Frost’s “The Silken Tent” and T. S. Eliot’s “Burnt Norton”. I’m probably just projecting, as these are two of my favorite poems that I memorized many years ago and still recite at the drop of a hat. On the other hand, I can’t help pointing out that Yau Ching is steeped in English modernist literature. I suppose I could always ask the author, but then, I can’t help thinking, where’s the fun in that?

XYS: I’m struck by the easy depth of Yau’s poems, which balances a great, albeit tempered emotion with piercing, cinematic images. I wonder how you both handle that tenuous sense of ‘feeling’ in your translation work—what moves you, and how you achieve an emotional tenor or pursue a certain affect.

JCX: It’s tricky. One thing I really like about this poem is its arc—a stanza on longing, a stanza on loneliness, neatly symmetrical with the English “longing” and the Chinese “kong.” That arc, I think, makes for what you call the “tempered” emotion of the poem, its sense of being complete and yet unfinished at once.

SB: This is a really tough question, as I’m never quite sure what Yau Ching’s feelings are in any given poem as they are usually quite complex, as you point out, which is one of the reasons I’m drawn to her work. Which is why, apart from fleshing out the occasional cultural reference or literary allusion, I try to stay close to the wording of the source text rather than paraphrase or interpret what I think she might be saying.

XYS: One comment that many translators from the Chinese often make is that their translations can sometimes feel overladen, as there are so many references and historical/cultural gestures embedded within the language, but both of your translations have a levity to them. It must be different for every poem, but what do you think is the translator’s role in explaining or decoding the work for the reader?

SB: Well, I think the reason you find levity in her poetry is because it’s there; she’s quite a card. And yes, her poetry does reference other literary work and history and culture, but I would use the word “rich” rather than “overladen.” As for the second part of your question, I rather balk at the idea that the translator’s role is to interpret or decode a text, at least when it comes to poetry. I much prefer to think that his or her task is to preserve the reader’s interpretive freedom. It’s an impossible ideal, of course, but one worth striving for.

JCX: Ideally, of course, the reader gets to do their own decoding, their own word puzzling, via this and any other translation. In “Spacetime,” for instance, 時空 can straightforwardly be rendered as spacetime—in both cases, this is also the technical word used in physics for the concept of the spacetime continuum—but Steve chooses a zanier (and, I think, more interesting) option in his title “Timespace.” The Chinese poem anchors on the fact that the Chinese word kong, which Steve chooses to transliterate (and I do not), is also the word for space; however, the second stanza of our English renditions embodies the concept of space without explicitly naming it. Will a reader puzzle this out?

XYS: How do you feel about the idea of multiple translations—should they become standardised practice? Is there such a thing as inferiority and superiority between various translations, and if so, how would you structure such a hierarchy?

SB: I, for one, say, the more translations the merrier! No translation can possibly convey the richness, complexity and felt experience of a great poem in its original language. That’s one of the things that makes reading Virgil, Dante, Baudelaire, and the other great canonical poets such a pleasure: there are so many versions of their work to choose from and compare. Which makes me think that maybe we should stop publishing versions by a single translator, and instead publish multi-translator anthologies like the wonderful Poets in Translation series Christopher Ricks edited for Penguin Classics back in the 1990s, in which he included multiple versions of the same poem along with commentary, much as Chenxin and I have done here. Ricks organized the translations chronologically because, in many cases, each of the translators drew inspiration from or played off previous versions, which was certainly the case for me in translating this Yau Ching poem.

JCX: The more the merrier! One of the hardest things about translating is resolving several perfectly good draft options into a single published text. Multiple versions are a reminder that much as you’ll have to land on a final answer, the search for a definitive “best” translation might not be the most helpful way to frame things.

XYS: In the two translations that you both provided, Steve opted for a transliteration of 空 in the final stanza, whereas Chenxin translated the word into the English “empty.” I wonder how you both feel about the function of transliteration from Chinese into the English, or of its utility in general. What kind of passage or atmosphere does it create for the reader in the target language?

SB: I absolutely adore transliteration of foreign words, especially when the words are something we should know and may in fact know without knowing it—空kong being the kara- in karate 空手, though of course differently transliterated given the differences in pronunciation between Mandarin Chinese and Japanese. As kids we constantly encountered words we didn’t know in the books we read and that didn’t stop us from reading. Why should it stop us as adults? Especially in light of how easy it is to look up foreign words these days with Google Translate, Meta AI, and other translation apps at our beck and call.

JCX: There’s actually a fantastic backstory about the kara- in karate, in that the original word tō/kara 唐 meant Tang, a metonym for Chinese, and was altered to kara 空 (which means empty) during Japan’s jingoistic turn in the 1930s. So if a reader hears Zen echoes in the “emptiness” of kara-te, that’s not the only thing it contains—in fact, the Zen emptiness is at least in part a mirage, since the change was made for nationalistic reasons. And that, to me, is the tricky thing about individual words and the multitudes they contain: there’s almost no way to make those multitudes fully, simultaneously present to the reader, whether one chooses transliteration as a strategy or otherwise.

XYS: A pretty impossible element in Chinese to translate is the stylistic duplication of certain words to achieve a particular effect—musical, emotional, etc. Yau does this often: “細細”; “短短”; “白白”; “前前後後.” How do you handle such moments?

SB: Perhaps I’m wrong, but I think in most cases, the reduplication of adjectives is usually done for reasons of cadence rather than emphasizing or amping up the quality being modified, and so I tend to translate them as a single adjective. But then, again, for the same reason, cadence, I might repeat the adjective or, if the adjective is semantically rich or, say, a contranym like làn 爛, use two different adjectives, “ripe” and “rank.”

JCX: Yau Ching uses adjectives with great precision in this poem. Here’s a line that gave us translators some trouble: “我短短的 / 坐在這裏.” Steve captures the duplication with “short and brief”; I ended up with the line “for now I am / sitting here growing transparent,” in which “for now” corresponds to the brevity of the speaker’s act of “sitting” (insofar as sitting is an act). Yau Ching liked the line and ended up suggesting it as the book’s title—I hope it’s a good line, even though I’m still dissatisfied with the translation.

XYS: In “I Am a Foot,” Yau agonizes over having to “turn in a one-line biography.” If you had to inscribe your translation ethos as one line, what would it be?

JCX: I’m agonizing too. I’ll let Steve take a pass.

SB: Stay close to the wording, but ask yourself all the while, ‘Will this hook and hold the reader?’ and if not, putter about a bit and see if you can come up with something better.

Chenxin Jiang is a PEN/Heim-winning translator from Italian, German, and Chinese. She was born in Singapore and grew up in Hong Kong. Her translations include Tears of Salt: A Doctor’s Story by Pietro Bartolo and Lidia Tilotta (W. W. Norton), shortlisted for the 2019 Italian Prose in Translation Award, Volatile Texts: Us Two by Zsuzsanna Gahse (Dalkey Archive), and the PEN/Heim-winning The Cowshed: Memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution by Ji Xianlin (NYRB). Chenxin Jiang’s translation of Yau Ching’s poem “Trial Run” was a winner of the 2020 Words Without Borders–Academy of Americans Poets Poems in Translation Contest. She currently serves on the board for the American Literary Translators Association.

Steve Bradbury is an artist, writer and translator of contemporary Chinese-language poetry, who lived and worked for many years in Taiwan. His translation of Amang’s Raised by Wolves: poems and conversations won the 2021 American PEN Award for Poetry in Translation. He lives in North Central Florida.

Xiao Yue Shan is a writer, editor, and translator. shellyshan.com

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: