Perhaps for most of us, the idea of a poet still confers an indelible sense of the romantic, with odes and music and beautiful abstractions. For Paul Valéry, however, this association was at best weak, and at worst a diminishment of language’s complex facilities and capacity for precise worldly evaluation, never satisfying the sublimity and intensity that he sought in his writings. Thus, in 1896, he introduced an incarnation of reason and his “infinite desire for clarity” in a character named Edmond Teste, and this alter ego would remain one of the most enduring vehicles of thought throughout Valéry’s life. Now, in our December Book Club selection, Monsieur Teste, we are offered a fascinating collection of writings that track the poet’s evolving mode as he pursues his own consciousness in search of pure intellect and reason, puzzling out the dazzling relationship between language and existence. They are the imprints from a modernist icon’s search for self-knowledge.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

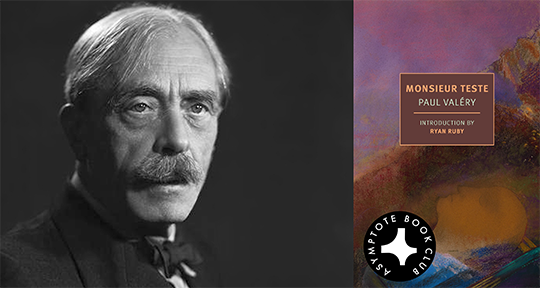

Monsieur Teste by Paul Valéry, translated from the French by Charlotte Mandell, New York Review Books, 2024

At first approach, it’s tempting to interpret Edmond Teste, Paul Valéry’s brainchild, as an embodiment of the poet’s own curmudgeonliness, as the character’s appearance roughly coincides with Valéry’s early renunciation of poetry and recession from the public eye. In 1892, shortly after launching into the Parisian literary scene and positioning himself as Stéphane Mallarmé’s successor—as well as being in the wake of a bad breakup—Valéry seems to have had enough of the bullshit. His frustrations with literature in the afterglow of Romanticism, with writers’ delusions of grandeur and pretensions of divine inspiration, prompted a sharp pivot toward the sciences. Heavily inspired by Cartesian philosophy, Valéry came to embrace a highly empirical, mathematical approach to creation, eschewing the abstractions and vagueness he’d found so tiresome in poetry. His primary focus shifted inward, and he became chiefly interested in the mechanism behind creative construction, the series of mental operations occurring within the creator’s mind, and in testing the outer limits of human capability. In his Introduction to the Method of Leonardo da Vinci (1894), Valéry marvels at the polymath’s ability to intake external data and investigate it with the utmost rigor in order to produce works beyond our fathoming—creations so staggering that the common man, the unenlightened thinker, could only attribute them to flashes of inspiration, invocation of the Muse, or some other abstract force that Valéry so disdained. In Leonardo, Valéry found an ideal creative archetype—the “universal man”—who “begins with simple observation, and continually renews this self-fertilization from what he sees” in contrast to the lesser, unempirical thinkers who “see with their intellects much more often than with their eyes.” Valéry remarks that “when thinkers as powerful as the man whom I am contemplating through these lines discover the implicit resources of the method . . . They can, for the moment, admire the prodigious instrument that they are.” Shortly after publishing this study, Valéry continued on this theme with the first instalment of the Teste cycle, The Evening with Monsieur Teste (1896). This and the subsequent works and fragments of the cycle have now been arranged in a single volume: Monsieur Teste, a luminous new translation by Charlotte Mandell.

The compilation is an extended study of the prodigious instrument that is Monsieur Teste’s brain, and, by extension, a tracing of Valéry’s philosophical development. We approach this strange specimen (whose name derives from “tête” [head], “témoin” [witness], and possibly “testes”) from different angles: through the recounts of Teste’s admiring acquaintances and friends, a letter from his wife Émilie, aphoristic jottings from Teste’s personal logbook, and a dialogue. After some time spent in the lab with Valéry’s creation, I’ll confess that the Testian modus operandi began to grow on me; despite his aloofness and inward-facing philosophical stance, Teste espouses a way of thinking and perceiving that foregrounds self-awareness, a witnessing stance, both in relation to the external stimuli of the natural world and one’s own mental apprehension thereof. What Valéry set out to accomplish with his Teste project was not an argument for self-absorbed hermeticism so much as a blueprint for intellectual liberation.

In his preface, Valéry reflects on the frustrations that prompted the project’s inception: “I could even think only with disgust of all the ideas and feelings engendered or stirred in humans merely by their ills and fears, their hopes and terrors, and not freely by their pure observations of things and themselves.” What Valéry gives us, then, is a thorough demonstration of how such pure observation might be performed, and of how, through the adoption of such a method, we might come to know ourselves more fully, becoming more stable (or, at least, cognizant of our own instabilities), and thus inoculated against manipulation by external forces.

Monsieur Teste is comprised of The Evening with Monsieur Teste (1896); Letter from Madame Émelie Teste, Extracts from the Logbook of Monsieur Teste, and Letter from a Friend (1924)—with the addition of a collection of drafts and notes that Valéry had assembled prior to his death but ultimately published posthumously in 1948. The works run the formal gamut from lyrical prose to gnomic aphorism, all of which Mandell translates with deft versatility, expertly matching Valéry’s rhythm and rendering that which Valéry himself characterizes as “vigorously abstract language” with adept comprehensibility. Mandell’s skill and poetic sensibility are especially apparent throughout the passages in which Valéry describes the physical world as an influx of parsable data flowing in through Teste and his companions’ eyes:

We both relinquish our ideas. We fall into step with each other and we watch the gentle, incomprehensible movement of the public thoroughfare sweeping along shadows, circles, ever-shifting shapes, fleeting actions, bringing at times someone pure and exquisite: a person, an eye, or a valuable animal, all casting a thousand golden shapes playing over the ground . . . We listen, with a delicate ear, to the mingling of the ample street’s noises, our heads full of the many nuances of clattering hoofbeats and the constant flow of people, vaguely animating the undercurrents, making them swell as in a dream, a kind of confused vastness whose magnitude wavers and gathers together all footsteps, the opulent molting of the world, the transformations of the indifferent each into the other, the general press of the crowd.

At the risk of using some of the effusive and overly emotive terminology that Teste and Valéry so abhor, the staggering beauty of such passages turn what might have been a dry, cerebral exercise into a fulgurant enchantment. The inward-facing focus of the Testian philosophy is felt in vivid external terms; we, like Teste’s admiring followers, are brought under his spell and invited to attune ourselves more closely to the natural world.

Valéry admits at the outset that his creation, this “demon of possibility,” this proposed way of being, is ultimately unsustainable. Referring to these thoughts as “Monster Ideas,” he acknowledges in his preface that they are “produced in the mind, seem true and fertile, but their consequences ruin them, and their presence is soon fatal to themselves.” And indeed, despite Teste’s perceptiveness to the natural world and his animal self, his existence ultimately runs contrary to life as we, mere mortals, understand it. Although physical pain remains an object of fascination for Teste, offering an entry into further self-knowledge and discovery, he regards emotions as “absurdities, debilities, useless, idiotic things, imperfections—like seasickness or vertigo, both humiliating.” The admission of humiliation surprised me—it seems to indicate a soft spot in Teste’s otherwise steel skull and a rather un-Testian inability to accept such weakness as natural. As Benjamin Kunkel so aptly points out in his review of this translation, human emotions inevitably resist suppression—and thankfully so, as they have given rise to some of Valéry’s most exquisite verses. The contrarian poet would likely insist that the emotive qualities in “The Graveyard by the Sea” (1922) were deliberately, dispassionately devised, and that his own feelings played no part in its composition, but the magnitude of Teste’s hostility toward emotion betrays an underlying insecurity: “the most violent emotions seem to have something in them—a sign—that tells me to despise them.—I simply feel them coming from beyond my realm, after crying, after laughing.” It is Teste’s resistance to this element, the ineffable—the thing that comes from beyond this realm and cannot be apprehended with Cartesian logic—that renders him fatal to himself. However, to his credit, it’s a demise that Teste has foreseen and accepts: “What a temptation, though, death is. An unimaginable thing, which gets into the mind as desire and horror by turn. End of intellect. Funeral march of thought.”

Perhaps Ryan Ruby is right in pointing out, in his introduction to this translation, that the text might find a foothold in “twenty-first-century America, where isolated, overeducated men, [stare] into the mirrors of their screens” and “seek consolation in monstrous ideas and only find the abysses of themselves.” Assuming Ruby is here underscoring the text’s potentially dangerous invitation into narcissism, the remark seems to overlook a key component of Testian philosophy, which is indeed one of self-absorption, but also a proposed set of tools for resisting manipulation by external forces. In one of Monsieur Teste’s final fragments, a dialogue with an unnamed interlocutor, Teste issues a warning that feels particularly applicable to this age of technology-enhanced (dis)information warfare: “Always demand proofs; proof is the basic politeness that is our due. If people refuse, remember that you are being attacked and that you will be made to obey by any means possible. You will be trapped by the pleasure or charm of anything at all; you will be impassioned by another’s passion; you will be made to think things you have not meditated on or weighed; you will be touched, charmed, dazzled; you will draw conclusions from premises others have fabricated for you.” If Teste’s counsel, here and elsewhere, encourages aloofness, it also urges the opposite: a kind of engaged circumspection. He reminds us that the failure to pursue truth through ratiocination or to control our reactivity can make us all the more manipulable, and thus his work is a pronouncement for us to fortify ourselves and defend our most precious possession: free thought.

Mia Ruf is a copy editor for Asymptote and a dubbing script writer by trade. She lives in Queens, NY.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: