As an essayist, literary historian, and critic, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra has been identified as one of the writers who wrestle with ‘what it means to connect the ideal of personal authenticity with wider forms of cultural identity’ by The Oxford History of Life-Writing (2022). As a poet, Modern Indian Poetry in English (2001) defines him as an experimentalist ‘who . . . has formed a poetic from local material, parody, and the conscious manipulation of chance’. In the late 60s, as a student at the University of Allahabad, Mehrotra started the avant-garde literary magazine damn you: a magazine of the arts, and later in Bombay, he founded ezra (1966-1969) and fakir (1966). In 1976, together with Adil Jussawalla, Arun Kolatkar, and Gieve Patel, he started Clearing House, a small press. Along with Eunice de Souza, they’ve come to be known as the Bombay Poets. Today, he is a renowned figure in contemporary Indian literature, with a voluminous bibliography spanning poetry, literary criticism, history, translation, and essays.

In this interview, I conversed with Mehrotra on The Book of Indian Essays: Two Hundred Years of English Prose (Permanent Black/Black Kite, 2020), an anthology he edited, its earliest essays appearing in periodicals that were, as Henry Derozio described them, ‘short-lived as bugs, and not so infrequent as angel-visits’; his translations of the fifteenth-century bhakti poet Kabir; and of love poems translated from the ancient Indo-Aryan language, Prākrit.

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (AMMD): Let’s talk about your selection process for The Book of Indian Essays: Two Hundred Years of English Prose (Black Kite, 2020). In an interview with Saikat Majumdar for Ashoka University, you commented that you had wanted to include V. S. Naipaul and Jhumpa Lahiri, but had to ‘narrow the field’.

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra (AKM): The suggestion to do an anthology of Indian essays came from Rukun Advani, the publisher of Permanent Black/Black Kite. We discussed a few names—perhaps also some essays to possibly include—but at the time nothing came of the idea. Then, in 2019, under a pile of brown paper envelopes, I came across one marked ‘Black Kite essays’. I’d recently finished reading the proofs of Translating the Indian Past and had been wondering what to do next. In that envelope was the answer: a bunch of photocopies, the beginnings of what became The Book of Indian Essays.

It was decided early on—more for practical reasons than parochial ones—to exclude writers who had spent most, if not all, of their lives outside India. The exceptions were Santha Rama Rau and Victor Anant, forgotten writers who I felt should be brought back into the conversation—not that any conversation was taking place. By leaving out Naipaul, Lahiri, and a few others, I was also able to bring in people like Gautam Bhatia, who is an architect, and the historian Sanjay Subrahmanyam.

Since the essay is more pliable than poetry or fiction, it has been wielded with considerable style and effect by writers who might be widely known for their work in their professional fields—as Bhatia and Subrahmanyam are—but are less visible as essayists in English. I’ve always been slightly more interested in the less visible than I am in those who are always in the limelight. The latter can look after themselves and are doing it very well. There will, however, come a time when present limelight will fade into the harsh glow of oblivion, and they too will be forgotten—which is why we need literary histories and anthologies.

AMMD: In selecting pieces for the anthology, you came up against the difficulty in accessing nineteenth-century Indian essays in English: ‘We live in a library-less universe in this country,’ you said, without the aid of the New York Public Library or the British Museum or ‘even a reasonably good American college [library].’ Can you talk about the archival work that editing the anthology entailed—in particular, the early Indian essayists such as Henry Louis Vivian Derozio, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Shoshee Chunder Dutt, or Hasan Shahid Suhrawardy?

AKM: When researching and editing The Illustrated History of Indian Literature in English, I’d think to myself: we now have a sketch of the history, but where is the literature it is meant to historicise? Often, I would come across references that only those who specialise in the cultural history of nineteenth-century Bengal would know. They would refer to the contributions that writers like Derozio and Shoshee Chunder Dutt had made to short-lived periodicals and newspapers, which are hard to come by. While I had become familiar with the names of such publications—India Gazette, The East Indian, Mookerjee’s Magazine—I had no idea of where to find them, short of a trip to the British Museum.

Luckily, by the time I was editing the anthology, Rosinka Chaudhuri’s definitive edition of Derozio had appeared from Oxford University Press, and Nottingham Trent University had published a selection of Shoshee Chunder Dutt’s Bengaliana, edited by Alex Tickell. That’s where I first read Dutt’s ‘Street-Music of Calcutta’. The title had intrigued me when I first came across it, but it took a British academic and Nottingham Trent—rather than an Indian academic and an Indian publisher—to make it available once again. Nineteenth-century periodicals and nineteenth-century Indian literature in English are both under-researched, if not largely unresearched. Or is Shoshee Chunder to blame that he does not use Twitter or Facebook to tell us that his collected writings were published in a six-volume uniform edition by Lovell Reeve and Co., 5 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, London, in 1885?

The Suhrawardy essay was sent by Kaiser Haq in Dacca, because he liked it and thought I might like it too. When the idea of the anthology was revived, that essay was among the first that came to mind. Had it not been for Kaiser, it wouldn’t be there; I would never have found it on my own. The role that chance plays in these things, in writing, mostly goes unacknowledged. Whereas one knows beforehand that the anthology will include an essay by Nirad Chaudhuri or R. K. Narayan or Aubrey Menen, Suhrawardy is someone who is largely unheard of. And even if one did know of him, the Calcutta Municipal Gazette (1941) wouldn’t be where one would go to look for his work.

It’s the possibility of discovering someone like him that makes the task of the anthologist akin to that of an explorer. The anthology will go the way of all books—perhaps it already has—but there’s always a chance that someone will find it and come across ‘Tagore at Oxford’, where they can read Suhrawardy’s account of the 1912 meeting between Robert Bridges and Tagore. The essay ends with Bridges remarking, after Tagore had left: ‘Tagore is an extraordinarily good-looking fellow.’ Bridges then strides to the mirror on the wall of his vast study and admires himself.

We know all about the vanity of writers and how fiercely competitive they are, but writers priding themselves on their beauty marks a new beginning—though to what, I don’t know.

AMMD: What marks off the experience of editing poetry anthologies versus essay anthologies? What about anthologies of critical and scholarly nature versus those which lean towards the personal and the familiar?

AKM: An anthology, whether of poetry or essays, is a pronouncement of the anthologist’s taste. If it is an anthology of contemporary work or includes contemporary work, it also gives you some idea of who the anthologist’s friends are. There is no such thing as an ‘objective’ anthology. That said, it is always possible that the anthologist will put her personal likes and dislikes aside and read the author dispassionately. It’s difficult—not that I’ve tried, but I suppose it can be done.

AMMD: In your translator’s note to The Absent Traveller (1991), an anthology of Prākrit love poetry from the Gāthāsaptaśatī, you wrote that to translate ‘is to share the excitement of reading’. Can you say a little more about this?

AKM: Reading and walking are among the few things that you can do which are both pleasurable and harmless. But while the beneficial pleasure of walking is restricted to oneself, the pleasure of reading can be shared. For instance, you can read the poem to another person, in the original or in translation. To translate, then, is to share that ‘excitement’ twice. You want the poem to be embraced and loved by those who cannot read the language in which it is written. You want to interrupt their morning walk, or their shopping, or whatever it is that they are doing, and, shaking them by the shoulder, say ‘Here, have a look at this poem.’ I’ve wanted others to experience the same excitement I felt the first time I read the poems that I’ve translated, whether they be Prakrit love poems from the second century CE, the songs of Kabir, the work of twentieth-century Hindi poets like Nirala, Vinod Kumar Shukla, and Mangalesh Dabral, or Shakti Chattopadhyay (Bengali) and Pavankumar Jain (Gujarati).

AMMD: Your essay ‘True Confessions of a Literary Translator’ describes your earliest memory with literary translation, as well as the delineation of the poet’s creative process versus the translator’s: ‘I’d been writing since my mid-teens and was eager to write more, no matter how the writing came. When I started doing this thing that I’m talking about, of translating without knowing the original . . . in some ways [it] felt similar to what I experienced when I wrote my own poems.’ You confessed to not always being able to ‘tell the two sensations apart’.

AKM: Whether you’re working on your own poems or a translation, the process is the same—with small differences. In both, you’re seeking a word that eludes you. If it is your own poem, you may not even know what you’re seeking till you find it, whereas in a translation you already have a hint, telling you where to look. That’s when you rush to a dictionary or a thesaurus. In any translation there comes a moment, early or late, when you release the poem from the source-text to which it had thus far been tethered, and you work on it more freely. How freely differs from text to text. A Kabir poem and a poem by a contemporary Hindi poet cannot be approached in the same way, but in both, somewhere along the line, the distinction between translation and original all but vanishes. You then may find yourself working on a translation as though you’d written the original yourself. That’s why my books of poems also contain a selection of translations. At readings, I am constantly shuffling between the two. Were it left to me, I’d put the poems aside and read only the translations. I like them better.

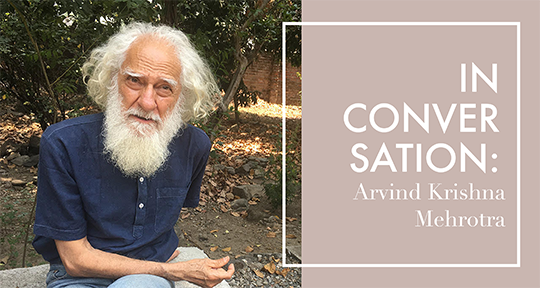

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, born in Lahore in 1947, is the editor of, among others, The Book of Indian Essays: Two Hundred Years of English Prose (2020), A History of Indian Literature in English (2003), The Oxford Anthology of Twelve Modern Indian Poets (1992), Collected Poems in English by Arun Kolatkar (2010) and The Last Bungalow: Writings on Allahabad (2006). He is the author of the poetry collections Nine Enclosures (1976), Distance in Statute Miles (1982), Middle Earth (1984), The Transfiguring Places (1998), Collected Poems 1969-2014 (2014), Selected Poems and Translations (2019), Collected Poems (2022), and Book of Rahim (2023); and the essay collections Partial Recall: Essays on Literature and Literary History (2012) and Translating the Indian Past and Other Literary Histories (2019). He has translated The Absent Traveller: Prākrit Love Poetry from the Gāthāsaptaśatī of Sātavāhana Hāla (1991), Songs of Kabir (2011), Vinod Kumar Shukla’s stories in Blue Is Like Blue (with Sara Rai, 2020), and poems in Treasurer of Piggy Banks (2024). He studied at the University of Bombay and University of Allahabad where he taught in its English Studies department for many years. He is now retired and lives in Dehra Dun.

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (they/them), Asymptote’s editor-at-large for the Philippines, is the author of M of the Southern Downpours (Australia: Downingfield Press, 2024), In the Name of the Body: Lyric Essays (Canada: Wrong Publishing, 2023), and Towards a Theory on City Boys: Prose Poems (UK: Newcomer Press, 2021). Their works—published from South Africa to Japan, France to Singapore, and translated into Chinese and Swedish—have appeared in BBC Radio 4, World Literature Today, Sant Jordi Festival of Books, The White Review, and the anthologies Infinite Constellations (University of Alabama Press) and He, She, They, Us: Queer Poems (Pan Macmillan UK). Formerly with Creative Nonfiction magazine, they’ve been nominated for The Best Literary Translations and twice to the Pushcart Prize for their lyric essays. Find more at https://linktr.ee/samdapanas.

Author photo credit: Seema Pant

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: