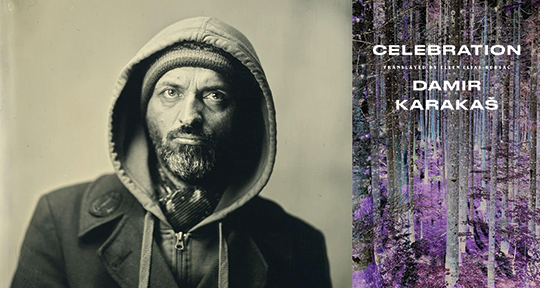

Celebration by Damir Karakaš, translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursać, Two Lines Press, 2024

An existential dilemma carries Damir Karakaš’s slim, engrossing Celebration, translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursać. Mijo—a former soldier of the famously brutal WWII organization Ustaše—is hiding in the deep, dark woods of a forest near his home, wondering if he will ever be able to come out. Connecting the dots of this character study is an intriguing exercise in a non-chronological narrative, which begins in 1945 before working its way back to 1935, 1942, and, finally, 1928. The structure allows for a series of carefully coordinated overlaps and repetitions, soaking the disturbing story line in the consequences and repercussions of an intergenerational fascism. Flashbacks and backstories included in each section gradually develop Mijo’s character, eventually revealing the lead-up to his seclusion.

In an interview with the Center for the Art of Translation, Karakaš provides a penetrating analysis of the historical and personal background of Celebration. When describing his birthplace of Lika, he speaks of “its poverty, its harsh winters, its wolves,” as well as the pervasive nature of war in the region; his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather had all served as soldiers, and Karakaš himself too is a veteran—though he has since learned to abhor war. The static nature of such an environment informed the author’s choice of the reverse narrative, which he applies to suggest that “we are always moving in a circle,” as products of all that precedes us.

The riveting opening in 1945 places Mijo amongst the trees near his house, having sequestered there to protect himself from the soldiers who want to execute him for committing crimes against the state. Mijo believes he is safe, camouflaged by the yellow-brown uniform that once identified him as a “tawny cat,” but he worries about the foliage shedding, leaving him “exposed to view.” His only consolation is that he is certain that his wife, Drenka, will never betray him. She had been “faithful to him all through the war. He remembered straightaway that this was why he’d married her, because he knew she would . . . never cheat on him.”

Mijo’s situation is unavoidably lonely: “In everything around him he felt the presence of isolation, in the leaves, the trees, the clouds.” But Drenka will occasionally come for a clandestine visit. She comforts him with reassurances that their family has stayed safe, but cautions that Mijo remains a wanted man: “They’re looking for you, every day they’re looking for you, they’ve dug up the whole village.”

As the disparate moments in the timeline of Celebration are gradually laid out, one is given passage to understand how a man becomes a killer, then a fugitive. Karakaš is assuredly subtle in his cues and descriptions, allowing the reader to gauge the chilling current of brutality and bleakness in some of Mijo’s most formative moments. When he is charged with eliminating the family pet, for example, he leaves the dog “firmly chained” to a sapling. When the dog begins to whine, Mijo runs out of the forest, trying to get home as fast as he can. With a rainstorm gathering around him, he “went down-hill through the yawning dark [and] began to bark. The faster he walked, the louder he barked: he felt as if he stopped barking, he’d die.” Meanwhile, at home, his mother has no milk for the baby, who suckles instead on an onion bulb. A cookpot doubles as a chamber pot. Mijo watches a man who carries a dead human body into the “torrent of dense, green forest,” and throws it into the “maw of a bottomless pit.”

Though Mijo lets it slip that “it all began with the celebration,” the full details and subsequent outcome of the event is not revealed until about halfway through the story. In 1941, on the day that Croatia is declared an independent state, Mijo, Drenka, and her arrogant brother, Rude, are trekking through the dense forest towards village festivities. They’ve brought along a rooster in preparation for the festivities, but when Mijo won’t kill the animal, Drenka grabs it “with one hand by the neck,” positioning it to be slaughtered amidst Rude’s taunts. Eventually, Mijo “swiftly cut it until its head . . . rolled off into the shining grass,” and what proceeds is an almost Shakespearean scene of eerie violence, leaving a figurative impression of the wartime cruelties that are still yet to come:

She walked calmly over, took it between her hands, and began to dig her fingers into it as if reshaping it, and when one more drop of blood had drained from the red tubes of its neck, she took it calmly by the feet, swung it twice and tossed it closer to the now-blazing fire.

Between these illuminating glimpses into the narrative’s social and cultural context, as well as Mijo’s own troubled history and complicity, Karakaš portrays his main character’s humanity, giving him the texture of simple desire and sympathetic emotionality. When Mijo moves into the barn near his house, he feels a “joyous thrill” to be “with his cattle, here, right underneath his wife and children,” and seeks to “hold on to the welling of happiness inside him for as long as he could.” He drifts off into sleep, “surrounded by his sense of safety and warmth that grew with each new thought of all the nice things that would come one day, once he was free.” There’s a certain purity in these passages wherein Mijo is overtaken by sensory, Proustian memories: “just as the lilacs in spring, young clover, dry hay were fragrances, and each time during the years of war he’d come across fresh dung, still steaming, he’d close his eyes and nothing could take him faster to the bosom of his home than that fragrance.”

Elias-Bursać’s sustained, supple translation is exemplary, suggesting that Karakaš’s original language lends itself to vivid descriptions, figurative imagery, and crisp exchanges. Mijo’s blazer is “faded from the sun and the teeth of time”; persistent rain falls “horizontally, vertically, but always like sharp needles.” Drenka’s contraband bag of food is “a hunk of bread, crunchy and yellow like the sun that had just set beyond the hill.” Of the ever-present forest, “so dense that a wolf might get lost in it,” Mijo observes that as “each new leaf fell . . . the leaves tugged with invisible threads.” Dialogue is also inscribed with bristling emotion, with voices that suggest how societal norms influence the discrete personalities: “So, Mr. Student, you’re gussied up like you’re going to a wedding”; “Blindfolded I’d know my way through this forest.”

Celebration is an astonishing read reminiscent of Boris Pasternak, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and Maylis De Kerangal. With its spirited prose, microscopic attention to character and environment, Karakas leads the reader into the individuals that make up the forces of history, refuses to offer any easy solution to the ravages of fascist-era Croatia and “all the human bones . . . carried off by beasts for years after the war.”

Robert Allen Papinchak is an award-winning freelance book critic in the Los Angeles area and a former university English professor whose reviews, criticism, essays, and interviews appear in The New Yorker, Publishers Weekly, World Literature Today, The Times Literary Supplement, Los Angeles Review of Books, On the Seawall, The National Book Review, The Gay & Lesbian Review, Mystery Scene Magazine, The Strand Magazine, Words Without Borders, and in newspapers, magazines, literary journals, and online. He was named Runner-up Finalist for the Kukula Award for Excellence in Nonfiction Book Reviewing by The Washington Monthly. HIs fiction has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and received an Honorable Mention from STORY magazine. He wrote two full length biographical/critical essays for Scribners’s two volume Edgar award-winning Mystery & Suspense Writers. He is the author of the well-reviewed Sherwood Anderson: A Study of the Short Fiction.

*****