When the cult writer Izumi Suzuki debuted in the English language with stunning, subversive short stories of counterculture and fantasy, critics and readers alike were astounded by her utterly individual voice, speaking candidly about emotional heights and lows, womanhood, and the chaotic world of drugs, music, and dreams in which her narrators found themselves. Now, we are given the chance to learn more from Suzuki’s own tumultuous life in the newly published autofiction, Set My Heart on Fire, written in the same mesmerizing, phantasmagoric tone of brusqueness and vulnerability that gave reality to her imagination. As our November Book Club selection, this novel enlivens the sharp mind, loves, and frivolities of a woman who sought and fought for her individuality, as well as the decades in which Japan was also undergoing changes of both revel and devastation.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

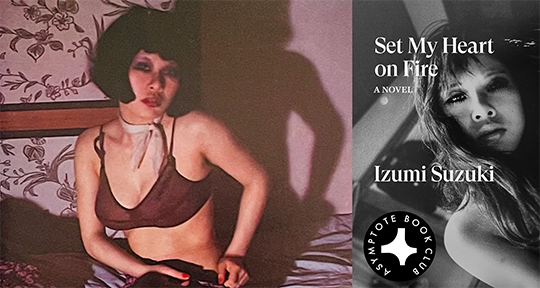

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, translated from the Japanese by Helen O’Horan, Verso, November 2024

Strung-out bass, clunky keys, psychedelic vocals. Abundant patterns, colors, and substances. Dancing, libating, popping, fucking. The groovy, knocked-out backdrop to 1960s Japan. In Honmoku, a district in Yokohama known for its American military base, Japanese youth had reveled in the abundance of American-influenced music, rock and roll, and rebellion, fueled by the financial prosperity of the “Golden Sixties” and its reigning youthful, nonconformist spirit. Izumi Suzuki, a prolific science fiction writer in the late 1970s, moved to Tokyo in 1969 with a year remaining to soak in that rhythm, as in the following decade, Japan would face the first hint of its coming economic breakdown as GDP growth slowed significantly during the global oil crisis. The former revelers, strung out and blissed out, were suddenly thrust into a decade of fading glory and no direction.

Izumi Suzuki’s latest work in English, translated by British linguist Helen O’Horan, is a novel titled Set My Heart on Fire—a notable deviation from the original title’s reference to The Doors’ “Light My Fire.” Song-inspired titles are a near-constant in Suzuki’s oeuvre, and her first novel in translation is no exception, with each chapter taking its name from a track from the sixties. While the references are upheld throughout much of the translation, O’Horan’s choice to alter the title better reflects the broader, underlying sense of desperation—for a dying age, a lost youth—and self-destruction that runs through the novel.

It is indeed a dulled, drug-clouded desperation that plagues these semi-autographical vignettes, underscored by the simultaneous sense of freedom and loneliness that accompanies nonconformity in Japan. As Suzuki recounts through her fictional counterpart in Set My Heart on Fire, after a couple of years working as an actress in “pink films” and posing for nude modeling, Izumi had a small breakthrough as a writer in the early 1970s, and thereafter retired from acting and modeling; instead of a lustrous career in writing (notoriously a boys’ club), however, she falls into a monotonous drone of day-to-day life, working “three days a month” and rotating between pills and band members to carry her through the night.

Today is just yesterday, continued. Tomorrow is just today, continued. Day breaks, night falls, day breaks. Night probably falls again. The little details differ, sure. But for the most part, everything is pretty much the same, and I feel neither more nor less sluggish today than I did last Thursday. I am sluggish. But still compelled to dance. Provided there’s some variety to the music.

And in the early years of the novel, there is always music. If Izumi is not specifically discussing or thinking about LPs and bygone stars, there is still a pile of accumulated records and memorabilia littering the scene—the lack of which is felt harshly in later vignettes as Izumi is twisted ever further into a dangerous, abusive relationship. But when the music is there, it sets the beat that keeps Izumi moving.

From the opening, The Golden Cups’ “This Bad Girl” sets the stage—a tumultuous, devil-may-care track that was all the rave in 1968, perfect for whirling around, flirting, and getting high. Izumi’s story picks up five years later in 1973, and Izumi, at twenty-three, is already feeling old.

‘Do you ever feel like you’ve aged really quickly? I feel like an old lady already.’ I leaned forward. I wondered whether it was just me who felt this, or if it was something about our era.

‘Yes, I do.’ Etsuko nodded. ‘Maybe because music’s dropped the psychedelia.’

Etsuko, four years Izumi’s senior, is an apparently successful music journalist (the first Japanese woman to interview Yoko Ono), aided by her naturally obsessive and opinionated personality. She, too, feels old and disillusioned, warning Izumi: “You’ll understand when you’re my age. Single at twenty seven. People don’t look at me. I can’t just smile sweetly at men. You should remember this. You’re too nice. You’re selling yourself short. All you have to do is ignore them. Men are only passionate at the start.” For this, Izumi views Etsuko as “frigid” and uncompromising, hopelessly implicated in a self-fulfilling prophecy to beat her partner down into leaving her. On the other hand is Izumi, who throws all of herself into her lovers, jealous and possessive, until another one comes along.

I’d pour highly concentrated, strong, intense feelings into a man. I’m sure it looked very fervent and emotional. I think it is. But there’s an affected quality to my affection.

I’m passionate, of course. Passion is something that occurs naturally. Yet when the time comes, I make it occur artificially. That seems different to ordinary enthusiasm. Distorted. There’s something forced and unnatural about it. I can cool it down at will. For me there’s little distance between loving and hating someone.

Izumi feels emotions at their extremes, and she considers ideas to their ends. In real life, her demeanor during interviews was commonly seen as scary: bold lashes, strange mannerisms, and a meandering, intense gaze, likely influenced by her chronic barbiturate use. In a largely conformist society such as Japan, Izumi Suzuki stands out. She is hot, and unashamedly so—she wants sex, to be touched, and more than anything, she wants to be loved. She wants to be loved beyond morality, and seems to feel a sense of pride for being the first woman a man cheated with, twice. She is “cerebral” and intellectual (as her friend remarks: “. . . this is usually a male trait, [but] talking with you means using my brain”), which stands out in a culture wherein women were thought to be driven more by heart than rationality. Her nonconformity puts a target on her back, allowing the people around her to feel comfortable trying to force her back in place.

‘You were born destructive. You’re drawn to the bad, you follow it compulsively.’

‘You’re too fond of destroying relationships . . . Once things seem to be going well, you smash it all up.’

‘You’re a terrible woman. . .’

‘You’re ungrateful. No matter what someone does for you, you treat it as your due.’

On the surface, Izumi rarely reacts, but internally, she accepts the critique (“No matter what happens, I tend to accept it right away as the way things are meant to be.”), and the barb is buried somewhere deep—waiting to boil over and consume her.

Another principal character, Joel (an obvious stand-in for Louise Louis Kabe of The Golden Cups), is similarly set apart from the world from his introduction. One of the most famous heartthrobs of the 1960s, Joel is waifish and beautiful, with feminine yet manly features, long legs, and a deep, empty stare. Since birth he has been distinguished as a “half,” mixed white and Japanese, and much like Izumi, Joel is open season for external opinions and criticism, accepting it from early on.

Joel was so lonely. Perhaps he didn’t realise it himself. But he did recognise his situation. He’d given up hope and accepted things as they were.

Like so, both Izumi and Joel are resigned to their lots in life. Izumi is drawn to him, first in glances on album covers, then in person as she gets his number and meets him for awkward sex in his tiny apartment. He is objectively strange, nearly out of his mind (“He didn’t seem human in form or in character. It was like being held by a plastic doll with glass eyes. He was like a photograph. No eroticism, nothing so human.”), but Izumi is hooked.

Joel is a stand-in for a bygone era, a symbol of when things were good and people were young. His time has passed. Izumi falling for him, beyond their shared difference, is an extension of the desperation felt during the 1970s—wishing time could go back, wishing things could be as they were. But at the same time, just like Joel, Izumi has given up. She has no sense of direction, no idea where life may take her, and she is resigned to whatever comes.

Despite this, throughout the novel, Izumi confesses time and time again that she wants to get married, even as her friends react with doubt and at times incredulity. But it’s true; Izumi wants to pour all of her love into someone. She wants someone to do the same for her. And just as love for her skirts the line with hate, the stronger and more painful the love is, the more it feels real—the more it pierces her. So when a man named Jun, a jazz musician with a sadistic current brewing under his skin, comes along and tells her that he loves her, that he wants to be with her forever, Izumi accepts it. Despite the growing dread.

Set My Heart on Fire is a story of lost youth, self-destruction, and the resignation that shadows nonconformity. A failing economy, a falling fervor, a futile future—what is there to do but take things as they come? Even Etsuko—who had tried to protect herself, who had advised Izumi against being too nice, who seemed like she wouldn’t be swindled by a man—ends up married and pregnant in a foreign country with an absent husband, alone.

At the beginning of the novel, Izumi had said to Etsuko that she already feels old; at the close of the story, it is clear that this confession had been a foreshadowing. Izumi’s youth began at the end of an era, and she lived through the confusion that followed. Time passes without her knowledge, and she eventually finds herself suddenly nearing thirty, mentoring a girl a decade her junior. She explains to her protégé what her own experiences had been like, seeing in her the promise of another muddied life.

Izumi Suzuki hung herself at thirty-six. Who could say why, but her daughter survived her and would go on to sue novelist Mayumi Inaba for her novel based on Suzuki’s relationship with her abusive ex-husband, Kaoru Abe, a “genius” alto saxist who seems to appear as Jun in Set My Heart on Fire. Her daughter’s objection to the novel didn’t mean much; it was adapted into a movie in 1995, one that begins with a shot of a fictional Izumi Suzuki walking up to a noose as her young daughter watches from the bed. Set My Heart on Fire, Suzuki’s own account of her life, was only published a year later in 1996, ten years after her death.

The reality is that women in Japan had very little to protect themselves at that time. I was talking to my partner, a man in his early twenties from Japan, about Izumi Suzuki, the novel, and her life. I told him how she’d been abused, and in response he said: “I mean, I guess domestic violence wasn’t really a crime back then. At least, you wouldn’t go to jail for it.”

As easy as it is to look at her decisions, her resignation and acceptance, and beg for her to do something different, the fact of it is: what could she have done? At a base level, men cheating on their wives was a given—and if it wasn’t found out, morally, they would be in the clear. Suzuki expresses this helplessness with clarity and lucidity, and O’Horan’s translation carries a matter-of-factness that only hints at the desperation and indignation coursing beneath. Late in the story, when a mother watches her son lead Izumi to his bedroom while his wife is out, she introduces herself politely, and while they Izumi and her son have sex, she fixes their shoes at the door. She’s accepted it. And the men who beat their wives were depraved—but in the social view, the wives should’ve known better than to go around with men like that. That was how things were. The optimism of the sixties that had fueled youthful hope and excitement was always going to fade. The atmosphere of love and possibility and the respite of drugs and music will sink to unvarying addiction and desperate nostalgia. The new era swings in with a final note: it’s time to face the music.

Bella Creel is a blog editor at Asymptote. She can be found on Bluesky and is working on a Substack. Find out more at bellacreel.carrd.co.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: