In the following essay, Charlie Robertshaw analyses the influence of Myanmar’s civil war on Burmese poetry, interrogating the expectation for writers and poets to bear “witness” to atrocities. Robertshaw concludes the essay in dialogue with eight Burmese poets, discussing the advent of the internet, gender and sexuality, and censorship in Myanmar’s literary scene.

For a more detailed historical overview of Burmese poetry, Robertshaw recommends Ruth Padel’s preface and Zeyar Lynn’s introduction to Bones Will Crow: An Anthology of Burmese Poetry, selections of which have been published in Asymptote.

No one

bears witness for the

witness.

— Paul Celan (“Aschenglorie/Ashglory.” Trans. Pierre Joris, 1942)

Are you still a writer if you don’t publish? Are you still a writer if you keep your writing locked in a drawer and only show it to people you trust? Are you still a writer if you destroy every word you write?

— Eula Biss (“The Price of Poetry.” The Massachusetts Review 42.1 (2001): 9-11)

For Burmese poets, to be able to fly the little kite ‘poetry’ high in the sky, they must start from very far away.

— Anonymous Burmese poet (personal interview, 2022)

The shock of Myanmar’s 2021 military coup has faded and global media attention has waned, but within the country, economic turmoil, forced recruitment, and the junta’s atrocities persist. As part of an ongoing campaign to intimidate, disgust, and dishearten onlookers, in October 2024 soldiers displayed the heads and limbs of dismembered civilians on stakes outside Si Par village, Budalin township, Sagaing division. Even recounting these atrocities provokes conflicting impulses—to “look” or to “look away”—and in the background, the longstanding ethical question, particularly prominent today as the the Gazan genocide is essentially livestreamed: what responsibility do we have to witness the suffering of others?

Carolyn Forché brought the phrase “poetry of witness” into the lexicon with her 1993 anthology of the same name. Forché argued that conditions of “extremity,” filtered through personal experience, “break” poetic form, from which a new literary space emerges: that of “the social.” In this space, poetry of witness addresses the (imagined, future, transnational) reader. However, Forché’s influential paradigm would be questioned and qualified in ensuing decades, with Cathy Park Hong stating in 2015 that “(i)n an era when eyewitness testimonies, photos, and videos are tweeted seconds after a catastrophe, poetry’s power to bear witness now feels outdated and inherently passive,” going on to consider Paul Celan’s weariness of his own “Death Fugue,” which, Hong observes, “turned into a mantra to ward off difficult engagement with the past.”

This passive tendency—to record atrocities rather than to resist—that Hong identified is a key issue in trauma studies, an academic field that emerged as a legacy of the Holocaust. However, Myanmar’s attitude to its recent past differs dramatically from the European and North American rhetoric of ‘facing’ the horrors of World War II. Myanmar’s ‘transition to democracy’ under reformist Thein Sein from 2008–2010 included transnational aid and investment (including in cultural production), the relaxation of notoriously harsh and arbitrary state censorship laws, and internet access through newly affordable smartphones, all of which gave Burmese creatives the liberty to determine when and how to infuse political motives into their work, and when and how their work would ‘bear witness’.

Prior to the democratic decade, the close-knit relationship between Burmese poetry and politics had several historical precedents. Verse was pivotal in galvanising soldiers before battle in the ancient Burmese kingdoms, for example, and in rallying troops during opposition against colonial British occupation. During the 1988 uprising, resistance songs played a vital role in amassing support and boosting morale, so much so that they have become inseparable from the uprising’s legacy. Indeed, so often were Burmese poets imprisoned under military rule particularly following General Ne Win’s 1962 coup, that an international support system has been specifically developed for imprisoned Burmese writers. Vicky Bowman, former United Kingdom ambassador to Myanmar, related that she used to urge Burmese friends who seemed in danger of being jailed under the pre-2011 iteration of the military government to put pen to paper, as they were more likely to receive aid if they were classified as a writer.

In this context, then, the modern act of bearing poetic witness in Myanmar might not be rooted in an effort to allow onlookers to recognise the suffering of another, nor even primarily as a means of prompting solidarity and inspiring social and political change, but rather as a pillar of bringing modern Burmese literature into a well-established tradition of resisting oppression with the pen alongside the sword.

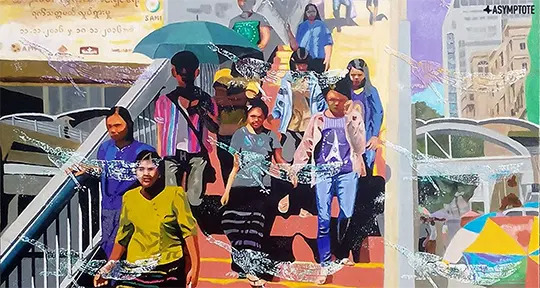

However, amplifying only the voices of political prisoners and activists runs the risk of reifying reductive humanitarian narratives around Myanmar. Myanmar is home to the largest book in the world (comprised of 729 marble slabs at Kuthadaw Pagoda in Mandalay), and to swathes of passionate literature lovers who keep the bookstalls crowding Yangon’s Pansodan street and the front of the colonial-era Secretariat building in business. Unsurprisingly, Myanmar has a vast and rich literary tradition, but translations from Burmese into other languages are rare.

As leading expert on Burmese film and literature Tammy Ho has observed, “the deleterious effects of Burmese militarism and ongoing forms of imperialism work to restrict the heterogeneity of Burmese cultural production from the global imagination,” echoing the academic bias which Burmese scholars Justine Chambers and Nick Cheesman called a preoccupation with “the suffering subject.” The latter were writing in 2019, more than halfway through the “democratic decade,” where perhaps some cautious optimism may have been warranted (at least, for the Bamar ethnic majority—2019 was also the year that The Gambia filed a case against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice for the genocide of the Rohingya ethnic minority in Rakhine state).

However, the possibility of a non-political Burmese literature gaining a foothold was brought to a halt overnight by the military’s February 2021 coup. Poets were once again among those targeted, tortured, and murdered by the junta, as is so often the case in Burmese recent history, and prominent young poets fled to the jungles on Myanmar’s peripheries to take up ranks in People’s Defense Forces (PDFs). The 2022 volume Picking off new shoots will not stop the spring: Witness poems and essays from Burma/Myanmar, edited by ko ko thett and Brian Haman, placed new post-coup writing alongside a tradition of witness writing, whilst on the Thai border where Burmese refugees have been fleeing for decades, Burmese-Americans poets Kenneth Wong and Maw Shein Win have recently begun leading remote poetry writing workshops. Notwithstanding the urgency of communicating the brutality of the current regime and the potential of the arts as a therapeutic tool, the danger remains of Burmese literature being once again globally conflated with witness poetry.

In November and December of 2022, I spoke with eight Burmese writers, mostly via Zoom, about this legacy of protest poetry and their identity as writers in the context of Myanmar’s political turmoil. Some conversations took place with the help of a translator; all have been lightly edited for clarity. My interlocutors were from a wide range of backgrounds, the details of which I have intentionally left vague to ensure their anonymity, and I have used “they” pronouns unless the person requested otherwise, or it was relevant to the content. Some of them are well-known, others emerging. Some described themselves primarily as writers, rather than poets (but all wrote “poetic” prose). The youngest was in their early twenties; the oldest, seventy at the time of our conversations. I selected my interlocutors via the “snowball method,” conducting some conversations with a random handful of writers in a small project that mushroomed in the borders between academia and personal interest, a laissez-faire approach to formality that seemed fitting for Burmese artistic culture, where copythachin, songs with Burmese lyrics set to popular western music, is commonplace, and self-publishing is widespread even for established authors.

One interlocutor described this attitude as a uniquely Burmese form of DIY. Fluent in Gen-Z inflected English, they started writing in high school, publishing chapbooks with friends like many other young writers in Myanmar, and their interest developed through university literature projects. “Poetry in Burma is not academically strong; we don’t have systematic institutions to study poetry and research. It’s kinda like street poetry, I guess. Poets studying by themselves and writing. Which is also good.”

It was impossible to talk about being a Burmese writer without talking about the advent of the internet, which ironically, during our discussions, the military had taken to blocking for several chunks of the day and disabling completely in some areas of the country. Covid-19 and the 2021 coup ushered in poetic discussions from the teashops and cafes of yesteryear into online Facebook groups, and these affective and intellectual networks are now mediated online. Most poets saw these online peers as an important part of their artistic development, noting how group members would translate books from abroad for each other. One person even said that their group constituted their “primary audience,” though it is noteworthy that that writer still published e-books with their poetic peers for a general audience. One poet said that even those who have since stopped writing poems are “like family,” while another described how their poetic family stepped in where their birth family was not initially supportive of their literary aspirations.

The move to online forums meant that poetry circles became less elitist according to many interlocutors—citing the cliques behind literary magazines, who, “if they don’t know you, won’t publish your poems,” as one put it bluntly. One older poet described meeting, via their WordPress site, a group of poets 5–10 years younger than them: “This younger generation has more freedom and they got to know each other online.” A poet in their twenties saw the internet not as a replacement for offline groups but as an extension of them, saying, “social media expands your literary circle.”

One poet even stated that if it wasn’t for social media, she wasn’t sure that she would have published her work at all. The poet’s gender is important here, although she herself didn’t make this connection in the statement. Burmese poetry, with a few notable exceptions such as celebrated poet Pandora, is heavily skewed towards men—a limitation that is obvious in the poetic groups’ traditional propensity for meeting in the male-dominated spaces of teashops. When the topic of gender came up, all the writers agreed on the lack of female representation, but due to my outsider status and the presence of a female translator, it would have been startling if male poets’ response to this state of affairs had been anything other than a gentle wringing of hands.

More telling, perhaps, was a poet who described leaving a poetry group after they recognised her work not for its considerable merits, but solely as the efforts of “a young lady.” Another, older female poet, however, said that she agreed with a division of poetic subjects by gender promoted by canonical Burmese poet Aung Cheimt. Another interlocuter added that, while thett and Haman’s Picking off new shoots will not stop the spring contains some expressions of same-sex attraction, the feminist poet Pandora and publicly queer poet Mae Yway are “quite brave” for their frank commentary on gender and sexuality. Poetic expression of sexual desire was a topic which caused division, with some considering taboos on such subjects outdated, and others accusing (especially younger) poets of speaking about such topics without subtlety or writing only for shock value. Discussing Myanmar’s conservative gender norms, one poet went so far as to say the “spring revolution” (resistance to the 2021 coup) was not only about fighting for democracy but about “breaking previous close-minded thinking.”

The hegemony of Burmese language in literature from Myanmar also reflects Burmese culture’s ethnocentrism. While not all the writers I interviewed were Bamar Buddhists, again interlocutors needed little prompting to express the need for more diverse voices from outside the majority ethnic group and religion of Myanmar. While Violet Cho and David Gilbert have provided the first English anthology of translations from poets writing in languages of the Chin, Shan, and Karen people, three of Myanmar’s eight major recognised ethnic groups, in Poems of Mya Kabyar, Tin Nwan Lwin & Khaing Mar Kyaw Zaw, there is still a way to go in expanding the linguistic and cultural diversity represented in literature from Myanmar. To this end, the internet has been instrumental as a means of organising and promoting writers who work outside of the hegemony, including poet Than Toe Aung, who in 2019 co-organised Yangon poetry slams via Messenger and publicised the oppression he experienced as a Muslim.

However, widening access to poetry via the internet has also had its drawbacks. At the time of our conversation, one poet had moved their work offline because of the amount of “annoying comments” garnered by attention from a wider audience who were not necessarily otherwise interested in literature. “After 2010, the crowd is different,” this poet observed, saying they were now considering going back to a writer’s blog, as in the earlier days of the internet.

Throughout Myanmar’s history of political turmoil, literature has played a pivotal role in resistance and perseverance for the nation’s people. Whether participating in poetry of witness or creating zines with friends in school, the material realities of living in a highly censored state has shaped Burmese literature and writers’ methods of expression. Surprisingly, a poet active before the democratic decade recalled the creativity of playing with words to evade the censor and expressed “appreciation” for a particular censor who really took the time to read their works. Even in the so-called democratic decade, censorship was still a threat. Writers were prosecuted for poetry, as a poet reminded me: “under Htin Kyaw the military would still sue you, so you had to self-censor.” One poet clarified that the excitement of the democratic decade was not only related to the lifting of censorship or to being exposed to the outside world, which many people had already accessed through the internet and translations. Instead, it was a sense of possibility: “the idea that you could write in any way—this was freedom.”

In response to direct questions about the relationship between poetry and politics in the contemporary moment, a younger poet declared that in their view, “writing from a third world country you can never escape politics, and it shouldn’t be considered separately. There is no freedom from the political situation; you will never escape.” Some other writers claimed that politics had a minimal impact on their work, depending on their personal style, but all agreed the relationship is, at least, always a crucial consideration in Burmese poetry. One sighed: “we are always asked this kind of question. In other countries it is not necessary, but in our country it is.”

Charlie Robertshaw is a translator and scholar of Burmese poetry, with co-translations appearing in Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine, among others.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: