Translators tend to like puzzles. Problem solving between languages is the definition of the trade, but what of the deeper, more invisible quandaries of culture and context? In this essay, Sam Bowden takes a look at two works that seem inextricable from the cultures of their origin—Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton and Rober Zemeckis’s 1994 dramedy, Forrest Gump—as well as their respective international adaptations into German and Hindi, to investigate the various methodologies and techniques utilized in fitting these quintessentially US productions for new audiences.

One of the translator’s greatest challenges lies at a level deeper than language: instead, it is rooted in the countless cultural and historical contexts which consciously and unconsciously inform a given work. Since language is inextricable from the culture and history within which it is made, translational processes often prove more complex than simply replacing words, rhymes, characters, and themes. Source-cultural conditions and consciousnesses can shape a text in structurally embedded ways that go far beyond its linguistic surface.

Speaking from the United States, I am well aware of the extent to which my country’s culture and history—one could even call it mythology—have deeply shaped the literary narratives it produces and exports on a massive scale. When American stories circulate through the world-system, the result can be curious to study: these are narratives visibly shaped by a suddenly-invisible context. How do translators maneuver around this?

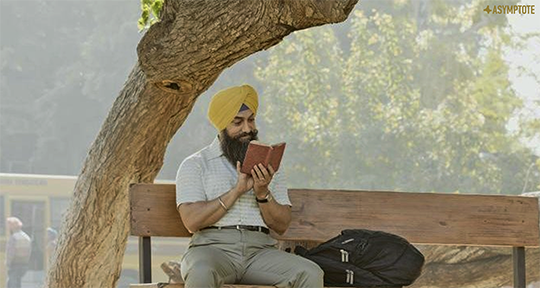

In two adaptations of immensely popular American stories that are fundamentally rooted in their Americanness, translating for different audiences poses unique issues. One is a 2022 German-language staging of the musical/Founding Father biofiction Hamilton; another, of the same year, is a Bollywood adaptation of the 1994 film Forrest Gump, whose main character (and title) is renamed to Laal Singh Chaddha.

Both of these translations have source texts that rely on an audience’s understanding of their imminently American narratives. For Hamilton, it is critical to possess some knowledge of the American Revolution and the resulting rhetorical and political struggles to build a new nation; for Forrest Gump, familiarity with mid-twentieth century American history is necessary to access and appreciate the many events subtly stitched into its narrative. Since both American historical fictions are immensely popular at home—Hamilton tickets resold for five figures, and Forrest Gump was 1995’s second-highest grossing film—the economic incentive for translation is high. This is to say nothing about the enormousness of US culture on the global stage, one still dominated by Western (and Anglophone) hegemony.

Perhaps it’s no wonder, then, that other countries are trying to replicate these works’ success. Between the two, Hamilton would perhaps present trouble for the translator in the more traditional sense: Lin-Manuel Miranda’s lyrics are laced with wordplay and references both historical and contemporary (with the show’s frequent winks at hip-hop providing a playful congruence and contrast to its discussions of eighteenth-century politicking). The difficulty of rendering this intricacy in another language may be familiar to anyone who has considered the difficulty of translating Shakespeare, Pushkin, or Bashō—how to recreate the original’s linguistic inventiveness and its narrative and aesthetic appeal?

Indeed, the duo behind the musical’s German interaction, rapper Sera Finale and longtime theater translator Kevin Schroeder, chose to creatively engineer solutions that prioritize the formalistic. With input from Kurt Crowley of the American production and Miranda himself, Finale and Schroeder have produced a fluid, fluent German rendering of the Broadway original, balancing meter and rhyme with narrative conveyance and relative adherence to the original’s music. Hamburg’s Hamilton, in short, translates its structurally-American story in a more “traditional” way: carrying over language and its necessary interface with music and meaning. Finale and Schroeder focus their efforts on the show’s lyrics, and only occasionally dip into spaces of paralinguistic ambiguity (such as moments when the original choreography clashes with its German lyrical equivalents).

Instead of being treated as an essential component of the text, the Americanness of Hamilton is decentered in Hamburg. The German cast and crew promote an interpretation of the text that shares the setting, characters, and historical setting of the original, but is more cross-cultural; they describe Hamilton in terms like “universal[ly] human” and more about “the relationships between characters” than the rise of the US and its values. As such, Anglophone Hamilton’s core is bypassed in favor of the human drama of its narrative. Of course, in some ways, American culture is so globally ubiquitous that it’s perhaps easier to conceive its cultural products as “universal,” as opposed to a text of a different background. When a work of this context is exported to a global audience, it’s unsurprising that those audiences prefer to interpret it in broader, humanistic, “big idea” terms. “Universality,” for interpretations of US products around the world, may also mean “unavoidable.”

Schroeder and Finale’s solution is admirable, but it’s also intriguing when translators decide to look beyond the linguo-formalistic qualities of the original text, opting instead to target shared cultural-historical understanding between that text and its readers or viewers. Much of the appeal of Forrest Gump (which is itself an adaptation of Winston Groom’s 1986 novel) rests in its many jokes that are dependent on an understanding of its specific milieu. When Tom Hanks’s Forrest calls the front desk of his hotel to complain about noisy, flashlight-shining neighbors and unwittingly exposes the Watergate scandal, the film doesn’t show us much more than the obvious symbols of that event. It doesn’t explain to viewers what exactly Forrest is doing here, and that’s how it operates throughout. Forrest Gump holds the expectation that its viewers will piece together the historical event on display—and thus the humor of the whole scene—from a collection of signifiers: Forrest at the Watergate, black-clothed figures rummaging through a neighboring room, a hard cut to Nixon announcing his resignation on TV. Thus, prior knowledge of US history is necessary to complete the joke. This is the great pleasure of watching Forrest Gump as someone familiar with the events being referenced: the movie will show us Elvis, the Vietnam War, and the rise of Apple through Forrest’s largely clueless eyes, and we’re expected to recognize what he cannot.

Structurally speaking, this presents a far more complex translational problem than Hamilton. For all its punning and syllable-juggling, Miranda’s script is more than happy to expound upon history (to the point where his songs are being assigned in classrooms), but Forrest Gump necessarily excludes the underpinning historical information so its audience can fill in the blanks. It’s the film’s comedic formula: Forrest stumbles into something new, and we get to point and chuckle, because we know what that new thing signifies for us culturally. A translation focused on linguo-musical form and narrative conveyance is sufficient for Hamilton to work in German, because the intrinsic textual information guarantees that most will walk away having understood the narrative—even those who aren’t familiar with the Articles of Confederation or the finer points of Aaron Burr’s educational background—and that’s how Schroeder, Finale, and their case have chosen to present it. But doing the same for Forrest Gump doesn’t make sense, as the film’s architecture is inextricable from its references.

Thus, a successful translation of Forrest Gump must consider cultural and historical context and the specific relationship formed with viewers: you come with your knowledge, and I’ll make jokes that rely on it. When awareness of American history cannot be as easily presumed with an audience of a completely different historical and cultural background, it becomes necessary to fill a base narrative formula with completely different ingredients.

This is what makes the translational feat of Laal Singh Chaddha so remarkable. While the film itself is not free of controversy (for instance, some questioned its representation of Muslim and Sikh characters), its translational relationship with Forrest Gump is still compelling. Screenwriter Atul Kulkarni swaps the American context of Forrest Gump for a narrative that unfolds in an Indian setting, but with a similarly winking methodology. Where Forrest accidentally inspires a young Elvis Presley, Laal teaches Shah Rukh Khan to dance. Forrest serves in the Vietnam War; Laal is part of a parachute battalion in the Kargil War. The references to Apple—a joke which leads to Lieutenant Dan’s sudden fortune in Forrest Gump—becomes a gag about the Bombay Stock Exchange, which Laal’s friend Mohammad invests in on a whim. The format is identical, but the pieces have been adjusted for Bollywood viewers. Kulkarni spares no details in recreating the story specifically for its target region; even Forrest’s iconic chocolate box is replaced with a box of golgappas.

It isn’t that Schroeder and Finale’s Hamilton is entirely bereft of these clever contextual translations as well; it’s impressive, for example, how they work German rap lyrics into lyrics that cite the Notorious B.I.G. Yet America is still its stage, providing both the framework and the contents of its narrative. Laal Singh Chaddha, in comparison, is fully dependent upon its reworking because of how its course material worked with its own cultural specificities.

There’s much more to say about each respective piece. At least in market terms, neither has proven a wildly successful translation. Laal Singh Chaddha received mixed reviews and failed to make back its budget; Hamilton closed in Hamburg after just a year. One intriguing possibility behind at least the Hamburg closure—speaking once again to the sheer scale American culture operates on globally—is that audiences were both familiar with and fond of the original. Some English-speaking German superfans of Miranda’s Hamilton expressed distress upon learning that a work they loved so much would appear in another language, even if it was their own. “Universal” as the German actors might’ve interpreted the story, does its massive cultural influence not render America and American stories already “universal”? Yet there is still immense value in observing how these works apply their distinct methodologies to embrace narrative embedded in nationalized mythology. Both reveal much to us about how cultures fold into one another, and the efforts made by translators to make legible these international narratives in their own time and place.

Sam Bowden holds degrees in Russian and English literatures from Kenyon College. He is currently an assistant fiction editor at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: