In The Thinking-About-Gladys Machine, the idiosyncratic wonderments of Mario Levrero are exhibited in a dazzling array. This first collection was, as the author tells it, ‘turned back into pulp’ in its first print run, but has since grown with tremendous repute, leading into a dedicated following in both its native Uruguay and neighbouring Argentina. It’s easy to see how these tales enthrall; each sees Levrero pushing the narrative form ever further into the enigmatic and the expansive, and any subject, object, and space is rendered as capable of endless transformations, creating portals at the seams of experience for the reader’s own marvelling journey. On live the bizarre, the mysteries, growing and multiplying at the non-existent borders of imagination.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

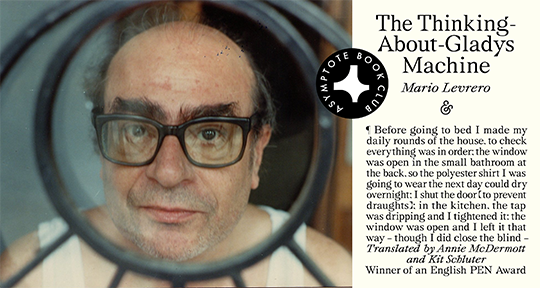

The Thinking-About-Gladys Machine by Mario Levrero, translated from the Spanish by Annie McDermott and Kit Schluter, And Other Stories, 2024

What does reality look like? Might it in fact be more dreamlike than we assume? Does true madness lie in the acceptance of daily routine? All these questions ricochet throughout the stories of The Thinking-About-Gladys Machine, a dazzling array of imaginative exercises from the eclectic Uruguayan writer Mario Levrero. The simplest beginnings—the daily rounds of a bedtime ritual, the anxieties of being late for work—take unexpected turns, leading us to places we never could have imagined. Along the way, chance is revealed to be the dominant factor in reality, rather than routine. Levrero is a dizzying stylist and he is matched with aplomb by translators Annie McDermott and Kit Schluter, who evidently share the author’s passion for imaginative play.

The Thinking-About-Gladys Machine is both a product of the imagination and a book that mirrors it; just like the human psyche, the diverse stories of the collection record both our meanderings and our obsessions. Often, our narrator is a Levrero-like figure: a good-natured, comedic man (prone to yearning for women, as the title attests) who follows his flights of fancy to their utmost ends. He is a charming narrator, skilled with wry turns of phrase, and his inability to leave any stone unturned takes him down curious paths. Whether it’s the miniature world hidden within a lighter in ‘Beggar Street’, or the young boy who grows old searching for a key in ‘The Basement’, Levrero plays with absurd economies of scale by stretching out both space and time. Reality and matter are his playthings, but the ensuing absurdity leads to some profound truths. Life, as Levrero’s literature evidences, is richer and more beautiful when we follow our whims.

The short story, in many ways, is the ideal constraint for this literary laboratory. Levrero participates in the rich tradition of Latin American short fiction, and while English-language readers may be more familiar with the philosophical narratives of Jorge Luis Borges or the neo-Gothic horrors of Mariana Enriquez, Levrero deserves to be named among the masters of the form. His stories are often characterised within the genre of the fantastic, and it’s easy to see why; he drills down into the unsettling characteristics of the everyday. If the fantastic is that which embodies Freud’s unheimlich (or ‘uncanny’), the heim (home) of Levrero’s imagination is a disturbing place, housing both fear and desire. Many of the stories take place in domestic settings, but they are far from cosy.

Levrero’s take on domesticity is exemplified in the two stories that title the collection: ‘The Thinking-About-Gladys Machine’ and ‘The Thinking-About-Gladys Machine (Negative)’. This play with the language of photography already gives you a sense of how these narrative exercises might play out, as well as their attentiveness to imagery. As readers, we never find out who Gladys is—only that a machine purrs as it thinks of her—and the focus is instead on a different kind of obsession: the nighttime ritual of tidying the house, which becomes one of fastidious control, to the extent that the reader begins to wonder why the narrator might be so cautious:

Before going to bed I made my daily rounds of the house, to check everything was in order; the window was open in the small bathroom at the back, so the polyester shirt I was going to wear the next day could dry overnight; I shut the door (to prevent draughts); in the kitchen, the tap was dripping and I tightened it; the window was open and I left it that way—though I did close the blind—

This latent anxiety pulses its way through the sentence, with its parentheses, asides, and run-on clauses. The brevity of the tale means that the tension is quickly relieved, but the end of the story is no simple resolution:

In the early hours I woke up feeling anxious; an unusual noise had made me jump; I curled up in bed with all the pillows on top of me and clutched the back of my neck and waited tensely for the end: the house was falling down.

Stuck in the continuous tense of the ‘falling down’, we are stuck in-between, left waiting for more. With such a neurotic narrator, there is no way to be certain if the last sentence is true, but the hesitation induced in the reader is a trademark of the fantastic: the feeling that the ground we stand on is less stable than it appears.

The only problem with labelling these stories as fantastic is that the category cannot do them justice; what Levrero does is resist categorisation, resist interpretation. If we are in the land of dreams, these are dreams that are not meant to be decoded. Instead, the author would refuse the label of the fantastic in favour of an ultimate realism: one that allowed for all the ridiculousness inherent to daily life. In a characteristically humorous exercise, the author once staged an imaginary interview with himself in the late 1980s (the piece has since been translated by McDermott). Fending off the suggestion of the ‘autobiographical’, he answers himself: ‘I’m talking about things I’ve experienced, but generally I haven’t experienced them on the plane of reality that biographies tend to make use of.’ Reality has multiple planes, many shapes—something exemplified in ‘Beggar Street’, in which a lighter that can only be deconstructed by the smallest screwdriver eventually takes up ‘more than half the room’. It is the power and stubbornness of the mind that drives the narrator to continue: ‘I think I ought to go to bed, but I can’t give up on my project.’ Innate inquisitiveness drives us further and further into the innermost reaches of Levrero’s reality. As the narrator remarks: ‘just as I’m getting ready to follow the thread out, I see a faint light ahead.’

In many ways, it is the pursuit of a fleeting image that drives these tales. In ‘The Golden Reflections’, an impossible sound leads to an impossible discovery in the basement: a pinhole with a view of a painterly scene that the narrator obsessively widens. The image at the heart of imagination is central to the Levrero project. As he argues in his self-interview:

I use imagination to translate into images certain impulses—let’s call these impulses experiences, emotions or spiritual encounters. The images could easily be different; what matters is passing on, by means of images, which in turn are represented by words, an idea of that intimate experience for which no precise language exists.

His fiction operates as a series of images—or perhaps photographic negatives, thinking back to ‘The Thinking-About-Gladys Machine (Negative)’: light etched onto film, burned into the retina.

And despite his claims that no precise language exists for the images he transmits, there is a clarity and precision to Levrero’s prose. Even in his most dizzying moments—such as the one-sentence virtuosity of ‘The Boarding House’—the form matches the fever dream of the content. Fine-tuned by McDermott and Schluter, every word leaves its mark. One example can be found in ‘Jelly’, an apocalyptic tale marked by random acts of horrific violence, rendered both shocking and absurd by the fact that the encroaching threat to existence is none other than an amorphous jelly, creeping across the land. McDermott translates one feature of this unsettling world as the ‘churn-up’, a social phenomenon somewhere between a stampede and a seedy public orgy, effectively using the onomatopoeic to capture both the chaos and the visceral disgust it evokes for both narrator and reader.

Another remarkable element of the book is the unity of voice felt throughout the collection, shared between the two translators. McDermott and Schluter seem attuned to both one another and to Levrero’s voice, and the result is remarkable. The dwelling examined in ‘The Abandoned House’ characterises the book as a unit: a series of mysterious rooms with unknown and unexpected surprises, held together within the container of the house. One knock on the door sets off a ‘whole host of strange echoes within the house’, and similarly Levrero’s voice echoes throughout the collection, like the unpredictable movements inside a pinball machine. You hear his comedy and curiosity throughout, even in the darkest of moments.

To summarise a talent like this is to fail: Levrero’s imaginary roves widely and reaches far into the depths of the unconscious, and to categorise him as simply another writer of the fantastic is to delimit an interpretation of his work that might close the reader off to the chance encounter that each page offers. But as McDermott and Schluter highlight, to translate his works is to open up possibilities: to tune into his idiosyncratic voice and transmit it to new readers, each of whom will bring their own imaginations to the text. Levrero’s boundlessness is an invitation to each of us: to imagine what might happen when we let reality be its strangest self.

Georgina Fooks is a writer and translator based in England. She is the Director of Outreach at Asymptote, and her writing and translations have been published in Asymptote, Hopscotch Translation and The Oxonian Review. She studied poetry translation at the BCLT Summer School in 2022 and is currently completing a doctorate in Latin American literature at Oxford, specialising in Argentine poetry.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: