09/09 Nine Japanese Female Poets / Nine Heian Waka Poems, translated from the Japanese by Naoko Fujimoto, Toad Press/Veliz Books, 2024

My parents were criticized for allowing a girl to study advanced language skills and piano lessons–for what–“Why don’t you keep your daughter in Nagoya?” Some teachers looked at me saying, “You are not even the smartest, nor a boy.”

Have you ever wished to be a boy? And have you ever interrogated the root of that wish? Perhaps you have been told by your family members that a woman’s role is not to utter garbage-talk like a hen pooping. Or perhaps your family’s insistence that you get married off has grown more insistent over the years. Maybe it’s shameful to admit that you’ve never been seated at the center of the table, that you’ve internalized a certain misogyny, or that you live in a society that has instated men as the heads of households, as breadwinners and intellectual superiors—not because they are smarter, but because they were given the opportunity to pursue their education.

This was the case for the men and women in my grandparents’ generation, who grew up under the Japanese occupation of Taiwan and the Confucian teachings that compare the “tiny man” (the scoundrel) with the “women.” I grew up learning about the Nineteenth Amendment and the Declaration of the Rights of Women in a neighborhood that largely continues to unlawfully segregate jobs by gender. The number of times I have been told that my writing is “frivolous” and that I was “not serious” about my literary career is innumerable.

How remarkable it is then to behold 09/09 by Naoko Fujimoto as a testament to the resilience and remarkable artistry of Japanese women writers during the Heian period (794 to 1185), a time of both gender segregation and cultural flourishing. I find myself seeing my obstacles mirrored in the Heian court custom of referring to women by their relationship with their male relative, or in Fujimoto’s lament in being called out as “not even the smartest”—with smart being measured by her ability to repeat what she has memorized verbatim on these make-you-or-break-you high stakes examinations that are characteristic of East Asian countries like Japan, Korean, or Taiwan. The idea that only the “best women” are afforded the same education as the most ordinary man is pernicious and deeply ingrained in East Asian society, even with the ongoing women’s rights movements in those countries. That identity is further complicated in East Asian-American communities overseas, where western values of independence clash with Asian values of Confucian filial piety and female subservience to men, and where leadership positions continue to be wielded by men in all types of professions.

Paradoxically, it is Fujimoto who goes on defying the odds, winning a full scholarship at Bread Loaf in translation and holding editorial positions at both RHINO Poetry and Tupelo Quarterly. These days, she also curates interviews with translators and illustrators at her Working On Gallery. Having defied the teachers who were incredulous at her parents’ investment in her education, Fujimoto had come across the seas to the United States as an exchange student and is staying here to forge her way in poetry and translation. I thought this context could illuminate why 09/09 is a singular example of the chapbook as art object—a text which, like 19 Ways of Looking at Wang Wei, demands multiple readings of what translation is, and how it can change one’s life.

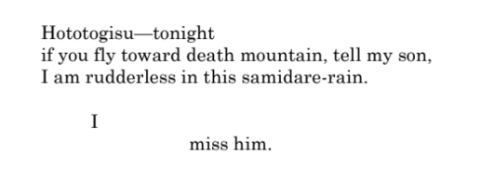

09/09 excels at uncovering complex feelings embodied in the waka, a classical poetic form written in the Japanese syllabary alphabet hiragana. In the Japanese original, waka is a syllabic verse composed with lines of 5, 7, 5, 7, 7 syllables respectively, but Fujimoto has rendered her translations to “restore some of the freedom of form in which these original works were made.” In doing so, she forges forward with her creative capacity in the open, even whilst the Heian woman hides hers behind the fan—as pictured in this comic “self-portrait” of herself as Sailor Moon.

Illustration by Naoko Fujimoto, used with permission

As its title implies, the collection features the waka of nine Heian woman poets, translated by Fujimoto, and each poet is introduced with a trifold interpretation. First comes a persona poem in the style of a haibun, written by Fujimoto in each woman’s respective voice; this is then followed by the waka, which is displayed in English translation, romanized hiragana, and the original Japanese; the waka and the poet are then further construed in a personal lyric essay. In these pages, Fujimoto takes us through the work and lives of Sei Shōnagon, Fujiwara no Teishi, Murasaki Shikibu, Kōkamonin no Bettō, Izumi Shikibu, Koshikibu no Naishi, Ukon, Daini no Sanmi, and Empress Shōshi.

The two stalwarts of Heian waka are Sei Shōnagon (author of The Pillow Book, a genre-bending compilation of personal observations) and Murasaki Shikibu (author of The Tale of Genji). It is remarkable how neither of these court ladies are known by their real names—as per Heian custom. They come near the beginning, while the empresses they serve—Fujiwara no Teishi and Empress Shōshi—bookend the other female poets, many of them contemporaries or daughters in the same circle. Despite being perhaps “lesser-known female poets,” Fujimoto asserts that they have “enormously influenced not only Japanese literary history, but also literature around the world.”

So we begin with the haibun in the persona of Sei Shōnagon: “A wall is something I build when I see you, it does not matter what type of seal.” That motif of the wall is carried through in Shōnagan’s waka—“but I made a decision / not to meet you again”—before Fujimoto carries us to see beyond the poetess at the pillar with her own memories, ascribed in the essay, of a teacher’s punishment: “He continued, ‘Memorize the first chapter of The Pillow Book if you want to pass.’” Fujimoto then revisits the syllables that took her nowhere, breaking them down visually to the essence of uncertainty; instead of relegating the poems to academic monotony, she expresses a wish to know the poet’s real name.

Fujimoto doesn’t mince words about the firm hierarchical structure extolled by a strong empire, putting classical literature, which was to be memorized through rote memorization, in stark contrast against the waka form, with its fluidity and possibilities of interpretation. In her translator’s note, Fujimoto explains that “[w]ritten waka was commonly used as house decor in seventh-twelfth century Japan, so line breaks varied from piece to piece and were not historically five lines per stanza, which is how waka has typically been presented in English-speaking countries.” Thus, the line breaks and enjambments in her translations can be compared to calligraphy. The artistic element is furthered with the whimsical illustrations of Fujimoto’s interior thoughts (reflecting how The Pillow Book is a kind of diary) on the cover; these illustrations extend the writing by providing another visual dimension, in which Fujimoto is not simply the translator, but also the author of these poems.

To give an example, the ninth waka poem, written by Empress Shōshi, is rendered as follows:

The use of white space as a visual element recalls Fujimoto’s use of “line-break hyperawareness,” which she elaborates on in an interview: “graphic poems have an advanced theory of line-breaks—how to navigate the reader’s eyes through poetic lines with static materials.” Here, the early summer rain is evoked with the “I” falling like a rain drop, down and down again with the “miss him.” The separation of the “I” also helps to show Empress Shōshi’s incredible solitude in the wake of her son’s death, which is detailed in the haibun preceding it.

Adjacent to the waka, the essays construct a sequential arc of Fujimoto’s journey—first as a student, and then as an artist in a world that discriminates against women writers. She records various experiences and lessons in her companion essays—of playing and then quitting the piano (an instrument she regards as inseparable from herself); of practicing hiragana calligraphy with her master/grandmother, detailing how the Heian women poets had constructed their waka in this script that was belittled as “women’s writing.” In another act of displacing gender, Fujimoto takes on the role of a boy in writing a henka (a response poem) to a girl’s waka, and “decides to be quiet as a clam at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean under a storm.” With quietude and humor, she looks at each of the masterpieces with a slant, pairing them with recollections of mandatory home economics classes for girls, of how she managed to finish “the burnable tanzen without my mother’s help,” and of her family’s own complicated dynamics, which are replete with symbolism. In the lyrical essay immediately following Daini no Sanmi’s waka, Fujimoto writes of: “[A] porcelain frog—kaeru—which means a safe trip back home,” which her mother gifts her on her trip back to Nagoya. In the next lyrical essay following Empress Shoshi, Fujimoto explains how she “was once a Japanese branch, and now [she is planting] a cutting for [her]self,” articulating a closure as well as a new beginning.

In vein with the waka, Fuijomoto’s lyrical essays are visually and linguistically rich; simple diction is mixed with specific Japanese terms, and a keen sense of beauty conveys a multitude of feelings. She harnesses both admiration and criticism of the culture that she grew up in, and in this collection, she pays tribute to that lineage, but also makes sure to take creative liberties of her own.

Tiffany Troy is the author of Dominus (BlazeVOX [books]. She is Managing Editor at Tupelo Quarterly, Associate Editor of Tupelo Press, Book Review Co-Editor at The Los Angeles Review, Assistant Poetry Editor at Asymptote, and Co-Editor of Matter.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: