From a glass casket for sculptures, to a piece of a burial figurine cast into edible gummy bears, and gelatin-based fish placed on silver platters, Ruoyi Shi’s whimsical oeuvre spans the realms of the organic and the inorganic, the imaginary and the real to interrogate the nature of truth, storytelling, and language. An interdisciplinary artist working across the domains of sculpture, video art, and writing, inspired by the oral histories and mythologies she grew up with, Ruoyi invents a singular kind of artistic practice that transforms not only personal memory but also collective history. “I am interested in how people are encouraged to appropriate any image they encounter, and how our vocabulary was chosen and formed in today’s society. I consider my work as fragments I collected for creating an alternative reality,” she says in a talk with Shoutout LA. In the following interview, I spoke with Ruoyi about the role that humor plays in her projects, reinventing historical objects, and the everyday precarity of living with language and mass media.

Junyi Zhou (JZ): I’d like to begin with your work Tomorrow’s Comforts are Here Today, in which you built a casket for your glass skeleton sculpture, as if it were a living entity. “I always call my art creations creature,” you wrote in your artist statement for this piece. It seems that the relationship between the organic and inorganic, or the dissolving boundaries between the two, are central to your body of work. Could you speak more about this?

Ruoyi Shi (RS): Exploring the boundaries between nature and artificial existence, as well as the notion of truth and its fabrication, has been a central theme of my practice. I see my art-making as a process of building an alternative reality—one that can be fragmented, chaotic, and full of coincidences. This reality of mine lies in the area where the organic and the inorganic slowly merge into one another. My goal is to mimic nature and capture the moments when nature exposes its unnatural side.

Many decisions I had to make in my art were neither preplanned nor expected. My immediate environment, materials, and time worked together to provide me with options, and my choices were directed by instinct rather than logic. It’s a form of collective creation. In this era we live in, the term “organic” has been deliberately shaped into a manmade concept. By placing our collective creations on a more equal footing, I aim to express greater honesty and respect for the elements beyond my control.

Tomorrow’s Comforts are Here Today (2021). Performance, writing.

Courtesy of the artist.

JZ: You work across various media, including but not limited to performance, sculpture, writing, and video art. Out of these different categories, your use of the last two especially fascinate me. Almost every project of yours incorporate elements of filming and writing, such as My Island, in which you recorded navigating one small patch of land that you call “my island” and wrote down your process of navigation. To me, they are an alternative kind of storytelling that embalms your practice forever in memory. How do you see the connection between your projects, the form they take, and personal memory?

RS: Memory is single-sided, inaccurate, and full of one’s own will and emotions. It tells us how we want to remember things. Many use amber as a metaphor for how memory preserves time. However, I see memory as a bubble bath. The colorful foams gently embrace our bodies, eventually flowing down the drain along with all the dirt and colors. As an artist, I am using the limitations of memory to construct a personal history that welcomes uncertainty.

Memory is not just visual—sound, smell, taste, touch, or even atmosphere can be the trigger. Thus, I need various media to make the memory as “real” as possible. In my work, I am not only the person who makes the physical objects but also the storyteller and narrator. My writing, word choices, and subtitle-making all guide the audience to engage with the reality I built. In some cases, my work actually becomes a manual or instruction for one to relive a piece of memory.

My Island (2021). Graphite on notebook paper, performance, 6:35 min video.

Courtesy of the artist.

JZ: In The Art of Everyday Conversation, you acted as an etiquette teacher to the parrots outside your window and forced them to follow specific instructions. The syllabus of this course is named “How to Become a Proper-Behaved Bird.” Could you tell me more about the role that humor plays in your work? What do you think about using humor to reflect systematic structures of discipline and obedience?

RS: There is a lot of game-inventing, rule-making, and playing involved in my work. I challenge existing disciplines by finding excuses and exceptions to their rules or by designing new systems myself. However, once I assume the role of a creator, these systems inevitably begin to crumble. My authorial standing is usually unstable as I combine rumors, mistranslations, and misunderstandings with facts to build the foundations of my reality. My need to establish new rules emerges because the old rules as I knew them no longer apply to my current condition. As an outsider living in a foreign country, my interests and perspective might be too “unique” due to my different cultural background. Many find them humorous because we don’t share the same habits of viewing our surroundings.

This sense of displacement, which many might perceive as humor, mirrors my relationship with language. I choose to work in a non-native language because I know fewer rules and haven’t learned its conventions. I often find myself inventing words or phrases as I struggle to find the most precise expression outside my mother tongue; I also become extremely straightforward. My straightforwardness doesn’t necessarily manifest as linguistic errors or inappropriate manners—it feels more like minor system glitches, like when the screen blinks or the edges of a continuous pattern don’t quite align. It’s absurd, or funny, perhaps.

In addition, I consider humor an accessible approach to creating a safer space for questions and discussions. It shows how vulnerable the systematic structures are, and its inherent absurdity reveals hidden issues and occasions spontaneous critique. I choose to use humor because it’s fun, relatable, and sensitive. It seems to counterbalance my authorial privilege as the artist and invite the audience to become active participants.

Syllabus for The Art of Everyday Conversation (2021).

Courtesy of the artist.

JZ: One aspect of your work that I find intriguing is the use of history and folklore. In Han 琀, for example, you transformed han, jade figurines placed in the mouth of the dead in traditional Chinese culture, into gummy bears. I’d love to hear more about the creative process behind this project. How did the idea for it come to you initially?

RS: This project happened during the pandemic when travel bans were everywhere and I was self-quarantining in Los Angeles. At that time, I was researching for my thesis project on the fish story from the first Chinese peasant revolution, and I was interested in non-verbal, tangible messages that we receive through our mouths. One day, my friend in China sent me a picture of the han artifacts she found in Hubei, simply because we both like small and strange objects. I immediately thought, how funny it would be if people could consume han in the form of sweet treats, as we now have so many reasons for failing to resist it.

Han琀 (2021). Three-channel video, 2:23 min, performance with ceramic, gummy candies, and ice. Courtesy of the artist.

JZ: Han 琀 sees you take an aspect of history that is otherwise obscure and mold it to your vision. Do you see this project as a revision of history? If so, what particular aspects of this historical ritual are you revising and why?

RS: I frequently play with the “retelling” of history or ancient stories in my work, which can be traced back to the influence of Lu Xun’s Old Tales Retold (《故事新编》). In Chinese, the word “story” directly translates to “old things of the past,” as if reality will transform into tales once something occurs. For me, the magic doesn’t lie in reenacting ancient stories in a contemporary context—those loops will always happen on their own. Instead, it’s about blurring the lines of time and blending the old with the new. When history aligns with current events, it becomes a prophecy, or a rehearsal for the future.

In the mouth and skull of the Marquis Yi of Zeng, twenty-one jade animal figurines have been found. They are burial objects that ensure the dead continue enjoy what they had when they were alive. Some believe that they secretly prevented the dead from telling the truth, as their mouths would be too full to make any sound. Placed in the mouths of the dead, these figurines made me realize that the mouth is such a mysterious but practical place to hide things: spies in movies swallow notes in a hurry, mythical dogs cause eclipses by devouring the sun and the moon, and the ouroboros consumes itself endlessly. To some extent, mouths are infinite and renewable virtual spaces that intimidate others into silence.

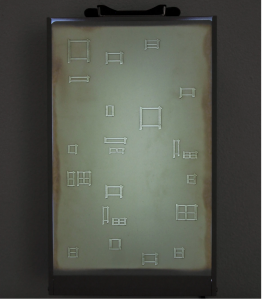

JZ: I now want to move on to your project (un)readable? (um)readable. In this project, you modified a paragraph written in Chinese, leaving only square shapes called kou 口, or “mouth” in English. You rightfully note that “the character kou 口 not only signifies actions involving the mouth but also serves as a fundamental element in the structure of other characters.” By stripping the paragraph into its bare minimum, you’ve divested it of its meaning, yet the kou 口 character itself affords myriad linguistic possibilities. How do you see this contradiction?

RS: When a computer system fails to translate certain information, it generates square shapes as placeholders, which resemble the character kou 口. This makes everything suddenly readable to everyone, as theoretically, any language can be translated into these square shapes. I couldn’t help but wonder—if the pronunciation of this symbol that represents endless possibilities is taught to everyone, would it enable everyone to understand each other, or at least allow people to communicate better?

The “(um)” and “(un)” in the title are the sound of silence. When a paragraph is reduced to just these “mouths,” the organs responsible for producing sound and meaning cease to function, as if they’ve become useless dead ends. It’s an ironic coincidence that the character kou 口 represents both the entrance and the exit, the known and the unknown. From ancient times to the present, regardless of the evolution of writing and the changes in fonts, this hidden code has persisted in all Chinese texts and records.

(un)readable? (um)readable (2024 – ongoing). Graphite on paper, wood, photo, light box with acrylic sheet, stereo photo viewer, 7 min video, performance.

Courtesy of the artist.

JZ: (un)readable? (um)readable brings to mind censorship in Chinese media where sensitive vocabularies in imported films and TV, such as 杀 (kill), are replaced by a square shape. I wonder if you had this phenomenon in mind while working on (un)readable? (um)readable. What do you think about this extreme form of meaning-making?

RS: I always have it in mind. Growing up in China, it’s hard to avoid experiencing censorship as it has violently forced generations of people into avoiding truthful self-expressions. We were taught to self-examine and consider consequences in a very rigid way, but instead of becoming softer human beings, we grew sharper and angrier.

Whenever I see a surveillance camera or a deleted message, I think of the three wise monkeys, each covering their eyes, ears, or mouth. They are popular in Asian cultures and are often found in temples, symbolizing the refusal to see, hear, or speak evil. “How wise they are!” We often say, admiring their rejection of outside information, as if information and knowledge are dangerous. To me, these monkeys symbolize our fear of language and information, because we know we can never be fully in control in the face of them. Human beings are born recorders and messengers, naturally equipped with the ability to invent new languages and understand them through our collective memories, which censorship cannot erase. Even in the most demanding circumstances, information still finds its ways to convey meaning, no matter how distorted it becomes.

I also think that when censorship occurs, the square shape suggest more information than the sensitive vocabularies themselves—it exposes the meaningless attempts to cover facts and the underlying policies and regulations. It’s a door to hidden narratives.

Ruoyi Shi is an interdisciplinary artist based in Los Angeles. Her practice delves into the translation and transformation of identity, history, and mythology through sculpture, writing, performance, and installation. Drawing inspiration from ancient tales and rituals that engage with language, societal norms, and cultural habits, she combines humor and fiction to construct her poetic narratives. Ruoyi was born and raised in Nanjing, China. She is a recent MFA graduate from the California Institute of the Arts (2021) and received her BFA in Sculpture from the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in 2019.

Junyi Zhou is a writer and an Assistant Editor (Visual) at Asymptote. She received her BA from Vassar College and MPhil from the University of Cambridge, concentrating on English and film studies. Her published work can be found in Mediapolis.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: